Gender Pay Difference Among Russian Graduates: The Profession’s Effect

The pay difference of men and women is a well-known phenomenon, although its amount and possible reasons vary by country. According to the Federal State Statistics Service (link in Russian), in Russia women receive 72.1% of men’s pay, although on average they are better educated and more often have a higher education qualification.

Usually, the following explanations are given for the pay difference of men and women:

-

Discrimination by the employer. It is assumed that some people for one reason or another (negative stereotypes, personal experience, etc.) may not like women as workers. If such people make decisions about hiring, promotion, bonuses, dismissal, they make a decision not in favour of women. It is with discrimination in promotion – conscious or unconscious – that the concepts of “glass ceiling” and “sticky floor” are associated.

- Social norms and psychological characteristics. Scientists record the difference in psychological characteristics of men and women within the general population (

willingness to take risks and to compete, aggressiveness,

self-esteem). In addition, it is important to have a public consensus about the role of women in society, about their “inherent” aspirations. Perhaps it is because of these factors that women are

less successful in pay negotiations, and are

more often offered low rates to start from.

- “Compensating differences”: individuals of different gender prefer

different jobs – for women, for example, proximity to home, confidence in the workplace, and flexibility of the work schedule are more important; for men, the best incentive is the pay amount.

- Difference in the accumulation of human capital. This point of view is based on the fact that men and women build different strategies for training and professional development before entering the labour market. Often, the difference in choice is a consequence of pre-market discrimination (biased attitude of the admissions committee, teachers) and differences in approaches to the upbringing of boys and girls (traditional views of parents on gender roles are associated

with less investment in girls’ education). The skills acquired by men and women during training are in different demand and are paid differently. In addition, women who are forced to take a break for maternity leave

may lose some of their professional skills, which also affects their pay.

-

Segregation and self-selection in the labour market. Men and women choose different universities, different professions and then fall into different sectors of the economy that have different pay levels and non-paid characteristics (for example, women predominate in the field of education, which is traditionally poorly paid, but has positive non-paid characteristics, and men predominate in the oil industry, where pay is relatively high, but production can be harmful). Within the same sector, men and women may find themselves in different positions, including due to the discrimination described above and the difference in accumulation of human capital.

In order to understand why men’s work and women’s work have different pay, we decided to focus on university graduates and see what gender pay differences there are at the very start of a career, and what these differences can be attributed to.

There is no consensus about the pay difference of graduates in foreign literature. In some cases, researchers discover this immediately after receiving a higher education diploma; in other cases, scientists, on the contrary, record the absence of a gender pay gap for graduates and its gradual increase with accumulation of experience and changes in marital status. For example, in 11 European countries, both southern and northern, in the mid-2000s, the gap averaged 23%, while more than a third of this gap could not be explained, which may indicate a large impact of discrimination, implicit segregation, and social norms on young workers. At the same time, a relatively large pay gap is recorded in Catholic countries of Southern Europe (Spain, Italy, Portugal), countries of Eastern Europe, and a minimum gap is observed in predominantly Protestant countries of Northern and Western Europe (the Netherlands, Sweden, Denmark, and Germany). Data from the British Household Panel Survey showed that at the time of entering the labour market a difference between the pay of graduates of different gender is not detected, but after ten years it is already 25 logarithmic points. The gradual increase in the difference also works for graduates of business schools in the United States. Estimates of the period after which the pay difference becomes noticeable vary – for example, data values for American graduates were obtained after five to six years, and even after one year. Such observations may indicate the greater role of all other explanatory models.

Russian graduates’ pay

We used data (link in Russian) from the Russian Federal Statistical sample survey of employment of graduates who have received secondary vocational and higher education. It was conducted in 2016 and contains the answers of 36,000 graduates of 2010–2015 about their education, place of work, position and pay, as well as demographic characteristics: gender, marital status and number of children, level of education, specialisation and employment, work experience, position, working week length, federal district and type of settlement. We limited the sample to people from 20 to 30 years old who have completed their studies or are studying in graduate school (to cut off working students).

An analysis of the survey results showed that among university graduates who entered the labour market, women’s pay is on average 21.4% lower than men’s (our related study, which also affects graduates of secondary vocational education, is published in a new edition of the magazine “Educational Studies Moscow” in June 2021; in Russian).

We used several methods to study what differences there are between graduates and what the role of these differences of pay margins is. The main one was decomposition (see the pull quote).

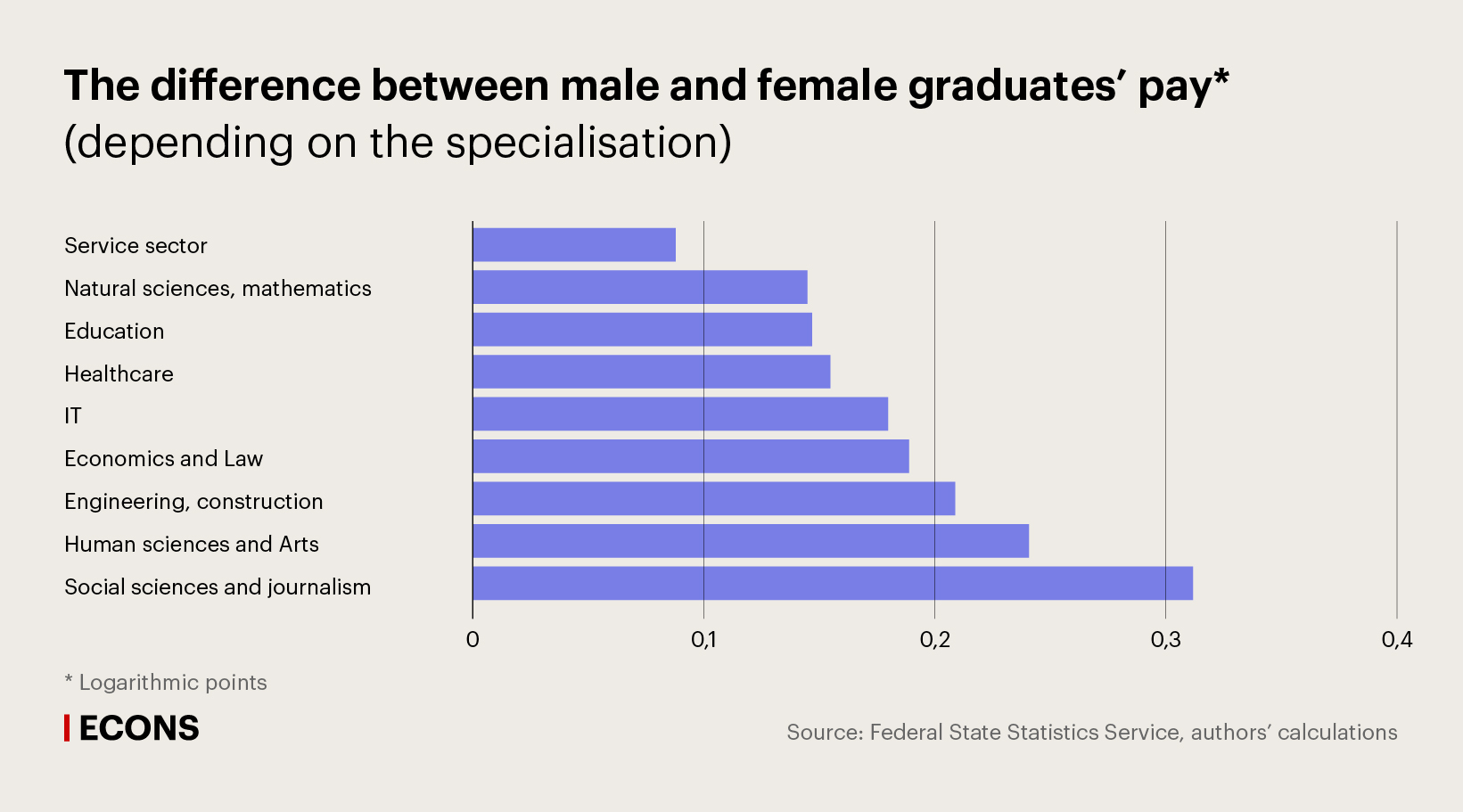

Our results show that one of the main explanations for the gender pay gap is segregation by fields of study and, as a result, by professions and employment sectors. That is, girls are more likely to choose educational programmes that lead to professions where the pay is lower in comparison with those professions that young men choose.

Traditionally, education and human sciences remain the “female” fields (according to the share of students), while engineering, manufacturing, and IT are the “male” ones. It is interesting that in the labour market, women and men are distributed more evenly by specialisations and industries than during training. For example, a graduate from a pedagogical university and a graduate from a veterinary university may both be employed in the trade field, and a graduate-lawyer and a graduate-programmer – in the field of public administration.

The difference in positions held between men and women who have recently graduated from university is small, and it has little effect on the pay gap. University graduates, entering the labour market, have little experience and rarely occupy leadership positions. But the higher the pay in a group of employees by their position, the greater the gender pay difference in it.

Segregation by profession, employment and position level explains a significant part of the gender pay gap – about half (43%). Nevertheless, more than half (57%) is accounted for by the unexplained part. This part of the pay differences may be due to discrimination – for example, preferences and stereotypes of managers and employees of human resources departments (“no one will listen to a female in our team” or “a man can’t be a normal secretary”), as well as unobservable factors (for example, differences in employees’ ambition and self-confidence, motivation and value attitudes).

The volume of the unexplained part (and the role of unobservable factors) of Russian graduates is comparable to what was recorded for Germany in the 1990s, Canada at the end of the 20th century, and some European countries in the mid-2000s.

It turns out that equal access to education for boys and girls, or even the predominance of women among those who have received an education, does not automatically mean a reduction in the gender pay gap. Individual’s pay still very much depends on the direction of study, that is, the choice made in high school. At the same time, it can be influenced by both the economic expectations of an applicant, as well as cultural attitudes, personal characteristics of individuals and social norms.

Thus, one of the ways to overcome pay differences is to involve women in training in specialisations that further contribute to greater returns on the labour market and allow them access to high-paying positions.

The researchers note that the profiling of men and women in different industries is formed gradually and is closely related to the translation of gender stereotypes in the learning process – through the attitude of teachers and professors, and interaction with classmates. It is important to instil in children and adolescents the idea that gender does not determine their success in a particular specialisation.

Ways to overcome segregation are associated with the creation of additional tools that support women in STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics – the collective name for a group of specialisations in natural and technical sciences): conducting mathematics competitions and workshops for girls, and allocating special scholarships and grants for women scientists. In some areas, a system of gender quotas and blind selection of candidates for positions may work. In addition, maternity support is allocated – if a woman is sure that she can combine employment and the role of a mother, she will be able to choose her study’s field more freely.