Income and Poverty of Highly Educated Professionals in Russia

‘ New poor’ (link in Russian) is a term coined by sociologists, analogous to the concept of the ‘new Russians’, a universal feature of memories of the wild 90s. The term has become associated with one of the social groups most affected during this period. Highly educated professionals often had no choice but to fill low-skilled jobs as unemployment rose. By the mid-2000s, when the issue of such professional poverty seemed to have become history, it had virtually ceased to interest researchers, and the term fell into oblivion.

But the problem had not been solved, it was merely smouldering and could flare up again, according (link in Russian) to sociologists from the Higher School of Economics (HSE). Natalia Tikhonova, Professor of HSE’s Faculty of Economic Sciences, and Ekaterina Slobodenyuk, Senior Research Fellow at HSE’s Centre of Stratification Studies at the Institute for Social Policy, compared the data on the employment, unemployment, and wages of holders of higher education diplomas based on surveys of the Russian Longitudinal Monitoring Survey for 2000–2019.

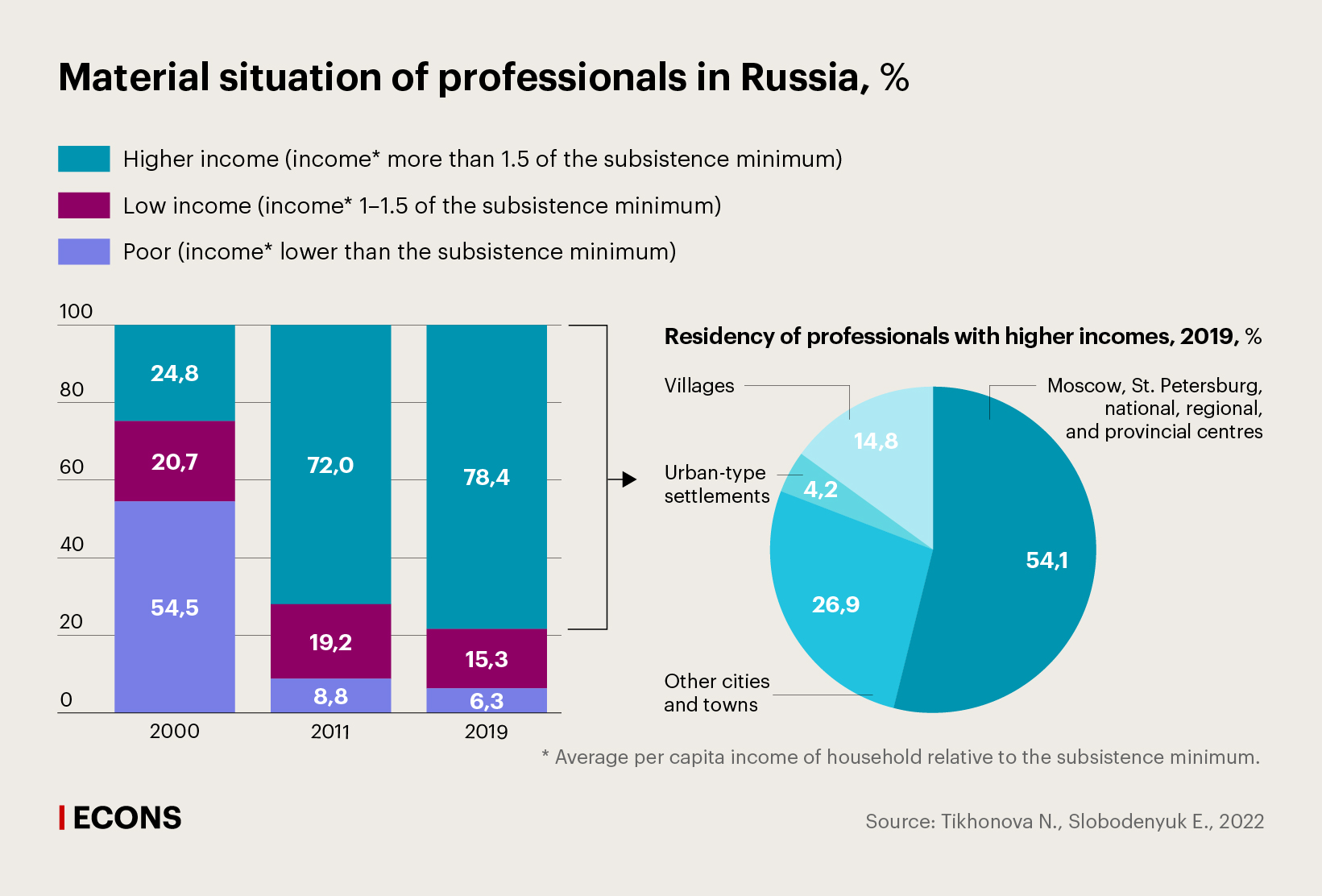

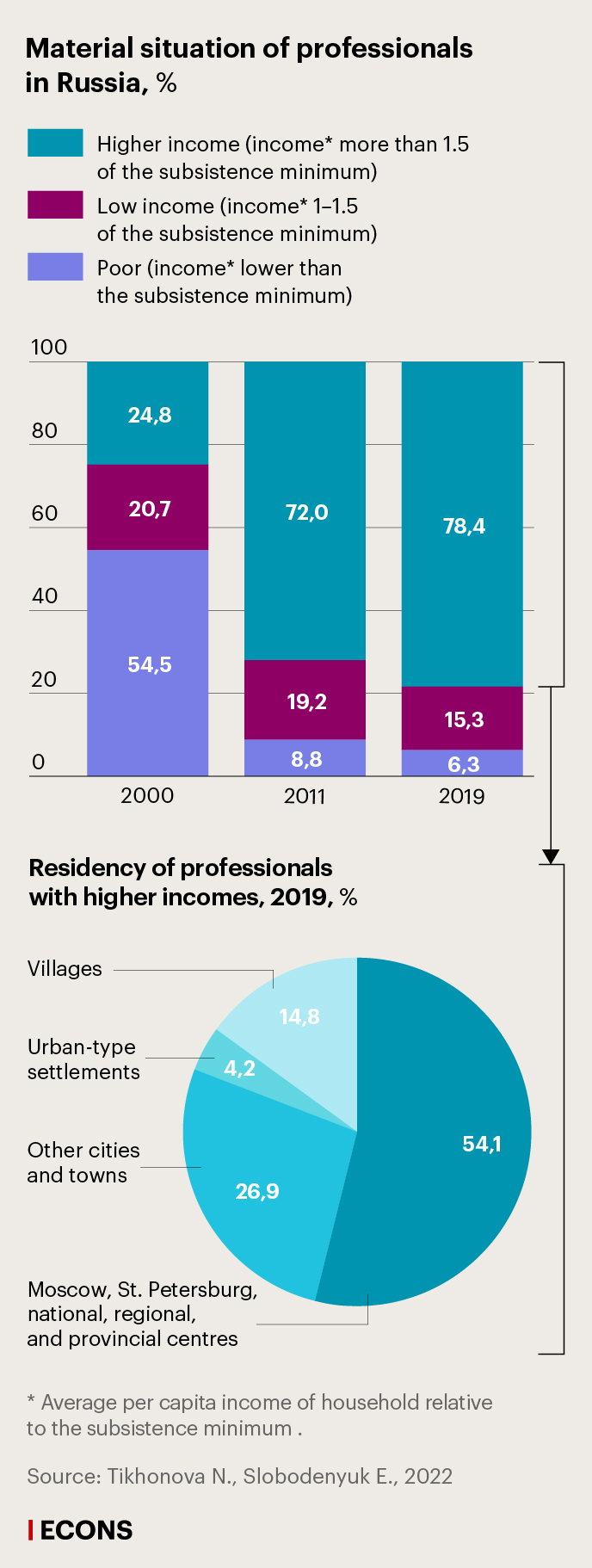

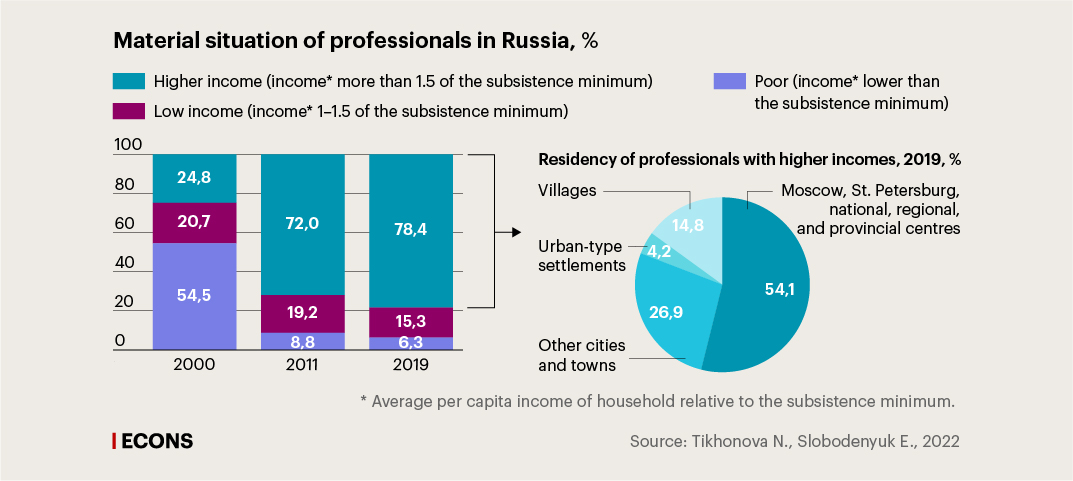

At the end of 2019, before the pandemic, more than one in five professionals in Russia, whom the researchers identified as those who were employed in the economy and had higher education, were living in poverty or on low incomes. This means that their income was below the subsistence level in the area in which they lived, or less than or equal to 1.5 of the subsistence level, respectively. The authors admit that this figure is well below the average of one third of all working Russians and appears to have improved since 2000, when more than half of professionals were living below the poverty line.

However, the main positive progress in reducing the number of poor professionals came in the years before the 2008–2009 crisis. Since 2010, the number of unemployed highly skilled professionals has increased, and the return on higher education has declined, with most professionals’ incomes approaching those of skilled or even unskilled workers.

That said, the relatively low salaries of professionals vary greatly depending on where they live. This increases the risk of poverty and low incomes for people living in villages and small towns. Nearly two thirds of poor professionals live in villages or urban settlements, and another quarter of them live in small towns. This situation is also related to the fact that a significant proportion of the educated professionals in villages and small towns are employed in education, where wages are relatively low.

Poverty and low incomes among professionals also strongly correlate with the number of minor-age children they have: almost half (45.6%) of qualified professionals with two children in 2019 were classified as poor or low-income.

The authors warn that these negative trends may exacerbate the economic impact of the pandemic. In addition to the effects of the pandemic, the Russian labour market, like the economy as a whole, will have to undergo significant changes due to international sanctions, and the current crisis will hit highly qualified professionals the hardest.

Professionals and human capital

The authors note that highly educated professionals are typically considered a relatively wealthy social group in comparison to other working groups and the base of the middle class. This is due to the fact that, in a late-industrial society, employee skills and knowledge are very important factors in production. In addition, according to the classic concept of human capital, skills and knowledge are the most important assets for the employees themselves, investment in which can be as profitable as investment in other types of assets.

The quality of human capital is most often measured by years of education. The average global rate of return on investment in education is 10%, which means that, on average, each additional year of schooling increases the future worker’s salary by 10%. The returns are usually higher in developing countries and emerging market economies. In general, the higher the level of education, the higher the income. For example, in the OECD countries, young professionals aged 25–34 with higher education earn almost 40% more than their peers with secondary education, and middle-aged people earn 70% more.

In Russia, this relationship is much weaker, but this was not always the case. During the transformative crisis of the 1990s, when the Russian workforce was redistributed according to the modernisation scenario, the return to education increased, reaching over 9% in the early 2000s, almost to the level of the global average. However, it has steadily declined since then. According to a World Bank study, the return to education in Russia had fallen to 5.4% by 2018.

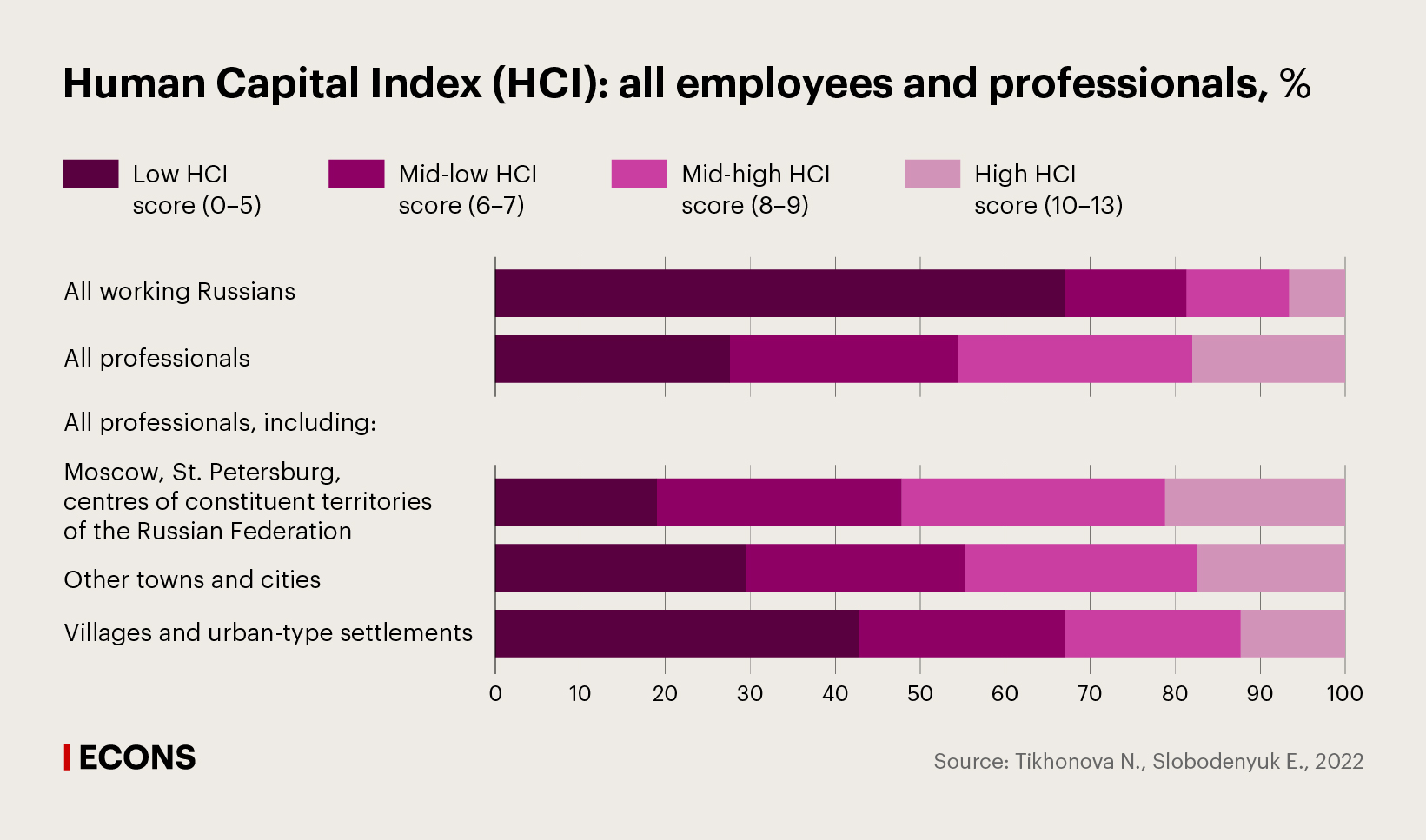

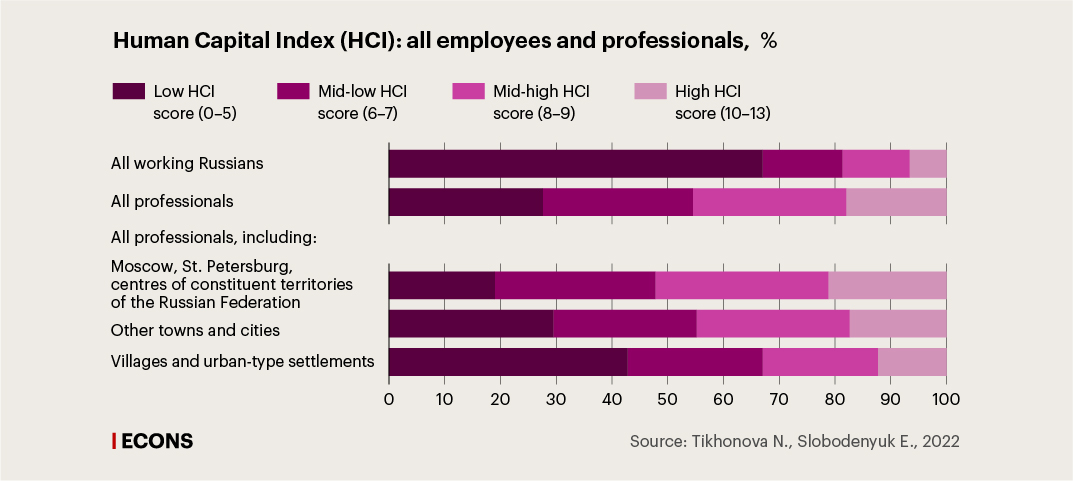

Tikhonova and Slobodenyuk note that, due to the decline in the return to education, the wages of most Russian professionals with higher education have converged with those of other groups, including blue-collar workers. According to the Russian Longitudinal Monitoring Survey, in 2019 the average wage of professionals was only 18.5% higher than that of all employees in the economy. Contrastingly, the median of the human capital index calculated by the researchers, which takes into account total years of study, knowledge of foreign languages, and computer skills, was 2.3 times higher for professionals than the median for the overall labour market — seven points versus three, out of a maximum of 13.

An HCI of 5–6 points is a score beyond which professionals can feel relatively safe, according to Tikhonova and Slobodenyuk’s calculations. In 2019 14% of professionals with HCI values from 0 to 5 were poor versus to only 4.3% of those with HCIs from 6 to 7. The group with HCI scores from 10 to 13 had the lowest poverty rate at 3.2%. At the micro level the poverty of professionals is primarily related to the quality of human capital, the researchers say.

However, only 18% of professionals have HCI scores between 10 and 13, so high HCI scores are not common even among professionals. The most typical HCI scores for professionals are 6–9 (more than half of all employees with higher education) compare to 1–4 for the total workforce (also more than 50%).

Risks for professionals

According to the researchers, the relatively low wages of professionals indicate an undervaluation of highly qualified non-manual labour in the Russian economy, caused, on the one hand, by Soviet traditions of free higher education and the predominance of ideas of social homogeneity, and on the other hand, by an imbalance in the supply and demand for highly educated labour.

The price of any good, including human capital, is defined by the relationship between supply and demand in the relevant market, and there may be a situation in which an abundance in the supply of highly skilled labour leads to a decline in or even the disappearance of the return on investment in human capital, and, the authors write, this leads to the growth of unemployment and poverty among professionals.

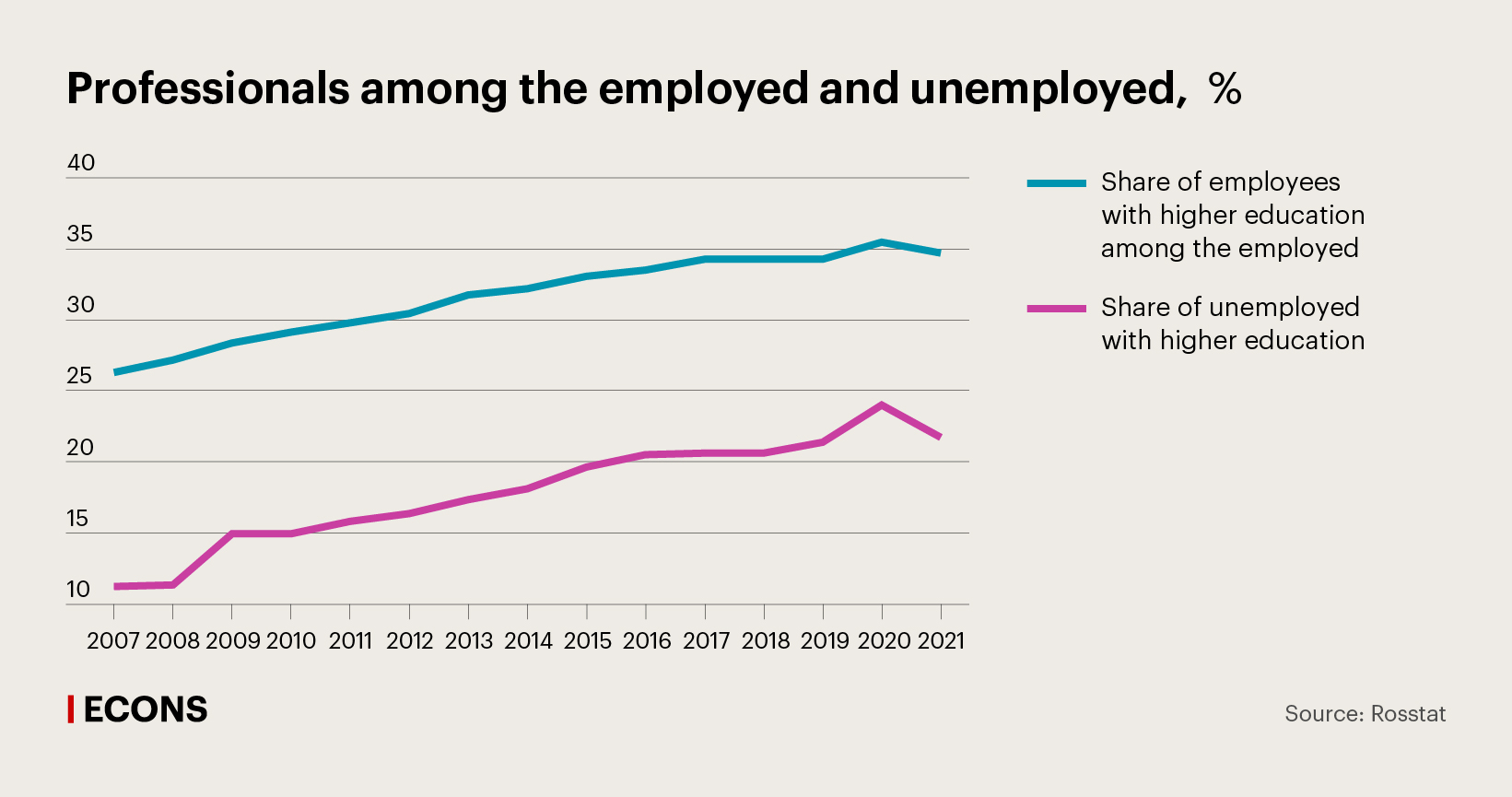

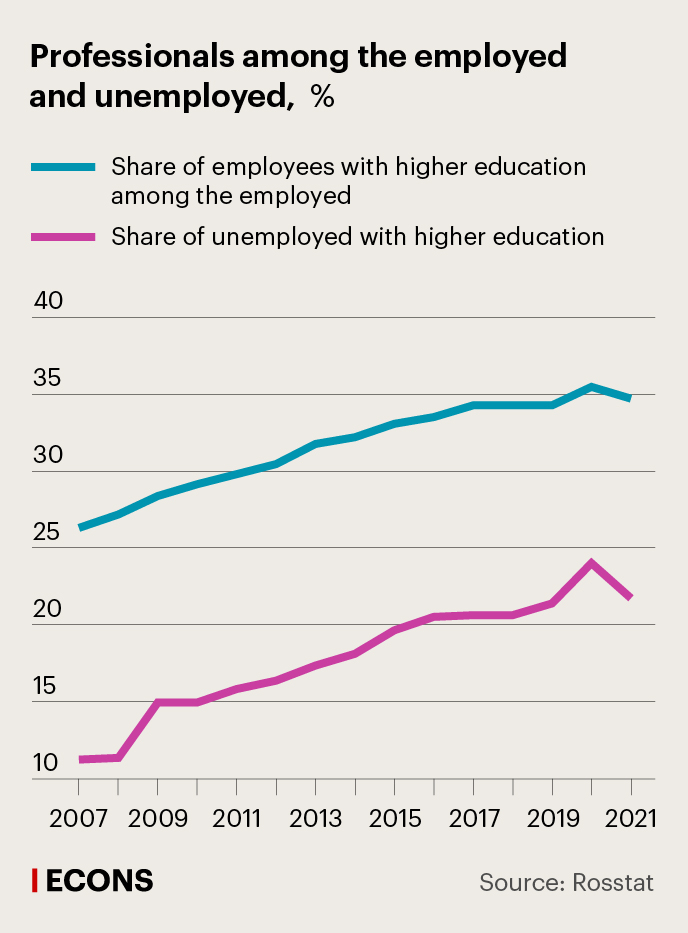

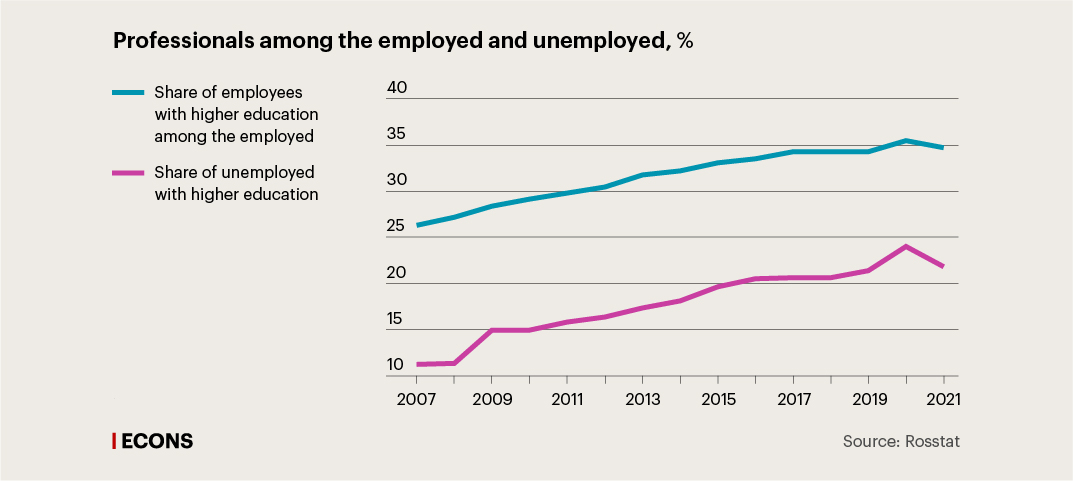

The decline in the returns to higher education was paralleled by a relative increase in unemployment among highly educated professionals that started in the 2010s: their share in the structure of unemployment has increased, while unemployment itself has been decreasing in the economy.

The main reason for these parallel processes is the imbalance between the number of people with higher education and the number of jobs in the economy that require it, Tikhonova and Slobodenyuk note. In 2007, according to Rosstat, holders of university diplomas accounted for 11.3% of all unemployed in the country, while in 2021 they constituted 21.9% (link in Russian). From 2007 to 2018 the share of people with higher education in Russia increased from just over a quarter ( 26.3%) (link in Russian) of all employed to over a third ( 34.2%) (link in Russian), while the number of jobs requiring a higher education remained virtually unchanged and accounted for slightly less than a quarter (link in Russian) of all jobs (24.6%), the same as in 2006 (link in Russian) (24%).

According to the latest data reviewed by the authors, in Russia in 2019 more than 6% of professionals were classified as living in absolute poverty, defined as having incomes lower than the subsistence level (in the country as a whole, such people account for 11%). This amounts to about 1 million people. Nevertheless, low incomes are much more common among professionals than poverty: more than 15% of them have incomes of less than 1.5 of the subsistence minimum or equal to it (while this figure is almost 22% for the country as a whole).

In addition to absolute poverty, as measured by the ratio of income to the subsistence minimum, there is also relative poverty: a level of income at which a member of a particular society is not able to maintain the standard of living that is typical for the society due to material difficulties that are not typical for other members of the society. The authors note that in modern Russia these risks begin to emerge when one’s income falls below 0.75 times the median income (link in Russian) of one’s region of residence. This level also serves as a lower bound for defining the middle class. There are more than twice as many relatively poor professionals as there are poor professionals in terms of absolute income: 13.4%, or about one in seven.

In addition to the general lack of demand for highly educated workers in the Russian labour market, the authors list macroeconomic factors that negatively impact the wages of Russian professionals — their main source of income — and put them at risk of poverty. These are:

- Residential inequality

Professional salaries vary greatly depending on where one lives. In 2019 the average income of professionals living in villages was 73% of the income of those in the centres of constituent entities of Russia, and 44% of the income of those in Moscow. In big cities with higher labour markets demand and higher average wages, even people with low Human Capital Index values are relatively better off: 28.5% of such workers earned below the subsistence minimum in 2019, compared to 70% of village residents with the same Human Capital Index.

- Sectoral inequality

Part of the reason wages vary by settlement type can be seen in the sectoral structure of employment. At the end of 2019, 55.9% of rural professionals were employed in education, another 12.4% in cultural institutions, and 4% in agriculture, that is, in industries characterised by relatively low wages. Conversely, professionals from the highest-paying industries are concentrated mainly in the big cities.

- Intrasectoral inequality

Professional salaries depend on company size: the larger the company, the higher the average income. Larger companies are mostly located in the major population centres, and this means that the differences within sectors, like those between sectors, are largely determined by settlement type.

As a result, where professionals live determines their employment opportunities — the size and location of businesses in a particular sector, in developing or economically depressed regions — and their risk of poverty. More than half of poor professionals live in rural areas, and over the years, poverty has become increasingly localised. In 2000 24.1% of all poor professionals lived in villages, while in 2019 they accounted for 59.2%, while the share of residents of large cities among all poor professionals decreased from 45.1% to 13% during this period.

- Household size and number of minors

In 2019 nearly one in two professionals with two children was classified as poor or low-income. Professionals with families of four or more members were 4.5 times more likely to be poor than those with smaller families, and those with children under the age of 16 were 5.6 times more likely to be poor than those with no children in their families.

This suggests that the salaries of many Russian professionals do not offer even the possibility of simple population reproduction, and, despite state support measures for families with children, the researchers conclude that there has been practically no improvement in this regard.

To reduce the risk of poverty some professionals refuse to have children or to have more than one child, the authors note. The average number of children under 16 in professional households is 0.68 versus 0.74 for skilled blue-collar workers and intermediate skilled workers and 0.71 for the country's total employed population.

Another particularity of Russia

The authors find that three standard methods of reducing the risk of poverty — migration, secondary employment, and acquiring additional skills — are ineffective for Russian professionals.

Surveys show that the migration of Russian workers with higher education is ever decreasing, in particular, from 2011 to 2017 the proportion of professionals with migration experience decreased from 31% to 24%. Tikhonova and Slobodenyuk believe this was probably due to the lack of resources for the least well-off segment of professionals to move and settle in new locations. Even if the quality of a professional’s human capital is quite high and competitive in the labour market of a large city, the effect is offset by the lack of the social connections that play an important role in getting the most attractive jobs in modern Russia, the researchers say.

Another way of increasing income — secondary employment — is also uncommon and is getting less and less popular among Russian professionals. From 2011 to 2019 the share of those who had side jobs almost halved, from 8% to 4.6%. Moreover, while in the 2010s secondary employment was seen as an opportunity to increase one's own income relative to that of others, today it is a means of maintaining income: secondary employment is dominated by those whose incomes are below the average for professionals, the researchers found. That is, this method no longer allows an improvement of one’s financial situation. In addition, there are limitations: time (the median workweek of those who have additional employment is 10 hours longer than that of those who work in one place) and skill level (a professional must have relatively high-quality human capital to find secondary employment).

After all, education offers a low rate of return in Russia, so attempts to increase one’s income through further education do not yield significant results.

Nevertheless, researchers have managed to find an effective method to improve the financial situation of professionals: changing jobs within their city while staying in their profession. Those who chose this path in 2019 increased their income by an average of 1.35 times. Paradoxically, however, they had the lowest human capital scores among all subgroups of professionals. The authors believe that such positive changes in life may require certain acquaintances, which not everyone has.

Tikhonova and Slobodenyuk conclude that the impact of poverty and low incomes on professionals is multifaceted and costly to the development of Russia. The poverty of professionals is not only a serious obstacle to the formation of the Russian middle class, but also discourages people from increasing their human capital. It also prevents the successful reproduction of the part of the population of the country with the greatest cultural and human capital.

The impossibility for professionals of even simple demographic reproduction without high risks of poverty and low income leads to a reduction in the birth rate among them and to limited opportunities to invest in the human capital of their children. Amid the increasing income equalisation of the population (link in Russian), the underestimation of highly skilled labour in the country exacerbates the potential for social tension in Russian society.