Labour Migration During the Corona Crisis

The coronavirus pandemic has worsened the situation for immigrant workers all over the world and Russia is no exception. The lockdown announced in March 2020 has forced many enterprises to suspend some or all their activities, especially in the sectors with significant foreign worker participation: construction, restaurant and hospitality business, and wholesale and retail sectors.

Economic growth depends on the amount of labour supply, and in developed countries, immigrants can account for a significant share of this supply. Labour supply is limited by an ageing population and a decline in youth labour force participation, rising education level, and structural shifts towards the service sector. Migration helps alleviate labour shortages emerging in some sectors and territories.

These trends determine labour migration to Russia. In the 2000s, the widening income gap between Russia and other CIS countries created conditions for the influx of temporary immigrant workers, especially from Central Asia. Russia’s demographic situation made immigrants even more important for the Russian economy: in 2007–2019, Russia’s working-age population (working age defined as 16–55 for women and 16–60 for men), shrank by almost 10 million people (excluding the 1.3 million Crimean workers who joined the Russian labour force in 2014). Increased retirement age is merely a temporary solution to the shrinking labour force but it will not reverse another trend: the aging workforce. For instance, in the early 1990s, people under 40 accounted for almost 60% of the population aged 20 to 60, in 2030, this share will be 40%.

Another factor in the inflow of immigrant workers is the progressive and progressing change in the educational composition of the Russian population. For example, in 2000–2019, the share of people aged 25–59 with higher education increased from 23% to 33%, while the share of those with secondary and lower-level education decreased from 32% to 23%. The shortage of low-skilled workers overlapped with the rapid development of the post-Soviet Russian service sector with its mostly low- or semiskilled labour, tough working conditions, and low wages. A significant proportion of these jobs are filled by immigrant workers.

Immigrants in the Russian labour market

Over the past two decades, foreign workers have become an integral part of the Russian labour market. According to the Main Directorate for Migration of the Ministry of Internal Affairs, in 2019, 5.5 million foreigners arrived in Russia for work purposes and registered as immigrants. More than 90% of them originated from the CIS countries, and more than 60% of immigrants were registered in Moscow and the Moscow Region as well as in St. Petersburg and the Leningrad Region. In addition, the Russian labour market also includes more than 0.7 million foreigners residing permanently in the Russian Federation on temporary or permanent residence permits or student visas. Moreover, the Ministry of Internal Affairs estimates that at least 2 million foreigners work illegally.

Restrictions on the entry of foreigners and stateless persons imposed by the Russian Government on March 18 have disrupted the usual course of labour migration, which had a distinct seasonal aspect. The influx of labour immigrants normally reaches its lowest in winter, while in March the flow starts increasing until May. For example, according to the data of the Ministry of Internal Affairs, in 2019, the number of immigrants that arrived in May was 3.5 times higher than in January. The number of issued patents – which equals the number of legal migrant workers from Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, Ukraine, Moldova, and Azerbaijan – in May 2020 was 10 times less than in May 2019. The number of foreigners registered as workers in April-June 2020 was 1.3 million less than during the same period of 2019.

This raises questions regarding the employment situation, expectations of immigrants staying in Russia, intentions of potential immigrants stuck in their countries of origin, and the scale of labour migration in the post-covid era. Answering these questions is important in order to understand labour supply trends and thus, the preconditions for Russia's post-pandemic economic recovery.

In an attempt to answer these questions, the National Research University Higher School of Economics and the Institute of Sociology of the Russian Academy of Sciences have conducted two surveys of immigrant workers. One was conducted online and included immigrants residing in Russia as well as potential immigrants who reside in their home countries but are ready to come to Russia in 2020.

Although online surveys are biased due to the specifics of the Internet audience (young, educated, mostly urban dwellers), the results give an idea of the current state of immigrants in Russia and the expectations of potential immigrants should traveling restrictions be lifted. About 2,700 respondents took part in the online survey: 1,300 foreigners residing in 78 Russian regions (of which 52.4% reside in Moscow and the Moscow Region) and about 1,400 foreigners residing outside Russia.

The second survey was conducted through telephone interviews (Computer Assisted Telephone Interviewing, CATI) among immigrants chiefly residing in Moscow and the Moscow Region. 300 respondents took part, mostly migrant workers with lower qualifications and education.

Lockdown and unemployment among immigrants

The online survey showed that the vast majority of Russian labour market participants were employed last year (88.8%). This year 8.7% of them were unemployed during the whole period from January to May. Employment reached its highest point in February, while unemployment peaked in April. The CATI survey demonstrated a similar pattern allowing for the fact that the respondents, mainly immigrants from Central Asia, are employed primarily in commerce.

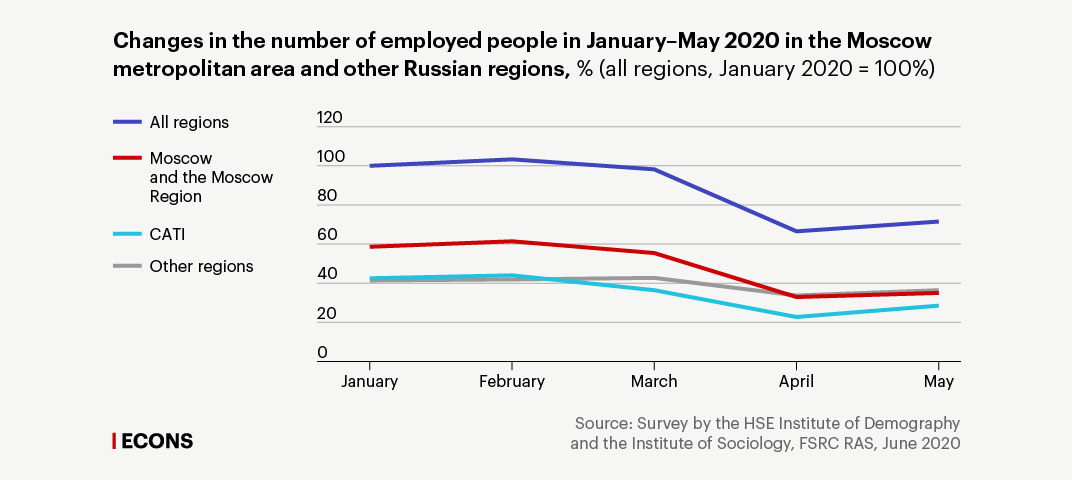

However, migrant employment trends in the Moscow metropolitan area in other Russian regions differ dramatically. The strictest self-isolation regime was introduced in Moscow and a rather tough one was announced in the Moscow Region, while in other regions, with a few exceptions, it was less strict and generally announced later than in the Moscow metropolitan area. Thus, in Moscow and the Moscow Region, the immigrant labour market saw a more significant collapse than in the regions (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.Changes in the number of employed immigrants in January – May 2020 in the Moscow metropolitan area and other Russian regions, % (all regions, January 2020 = 100%)

All regions

CATI

Other regions

Moscow and the Moscow Region

120

100

80

60

40

20

0

January

February

March

April

May

Source: Survey by the HSE Institute of Demography and the Institute of Sociology, FSRC RAS, June 2020

All regions

CATI

Other regions

Moscow and the Moscow Region

120

100

80

60

40

20

0

January

February

March

April

May

Source: Survey by the HSE Institute of Demography

and the Institute of Sociology, FSRC RAS, June 2020

All regions

Moscow and the Moscow Region

CATI

Other regions

120

100

80

60

40

20

0

January

February

March

April

May

Source: Survey by the HSE Institute of Demography

and the Institute of Sociology, FSRC RAS, June 2020

All regions

Moscow and the Moscow Region

CATI

Other regions

120

100

80

60

40

20

0

January

February

March

April

May

Source: Survey by the HSE Institute

of Demography and the Institute of Sociology,

FSRC RAS, June 2020

In the Moscow metropolitan area, employment began to decrease in March, while other regions saw growth in immigrant employment as usual for this period of the year. In April, the number of employed respondents fell by 40.8% compared to March in Moscow and the Moscow Region, while in other regions the decline was a mere 21.2%. It is noteworthy that the CATI survey shows the same employment dynamics as the online survey conducted in the Moscow metropolitan area. On the one hand, it is of no surprise as 95% of CATI respondents reside in the Moscow region. On the other hand, CATI respondents are employed in lower-quality jobs and this means that the crisis has had the same effect on workers of different qualifications.

Who kept their jobs

The April collapse of the labor market passed unnoticed for core workers. Employers seem to have prioritized keeping their most valuable employees, while chiefly getting rid of less experienced and lower qualified workers. More than half of those employed in January–May 2020 (55%) kept their jobs at that time. They are the most educated (28.9% with higher education), those with a better command of Russian, and many of them are Russian (32%).

The worst affected are the lower-paid and most socially vulnerable groups of immigrants whose legal status is unsettled – who do not have a valid permit of stay/residence and/or work in Russia – and the informally employed, whose employment is based on verbal agreements. The share of informally employed respondents is 38.7% (and it is more than half, 51.8%, among those working in micro-enterprises of up to 10 employees) but among those who remained in employment in January–May 2020, this share is significantly lower: 24.2%. Belarusians, Kazakhs, Armenians, and Ukrainians suffered the least from job cuts, while Uzbeks were hit the hardest.

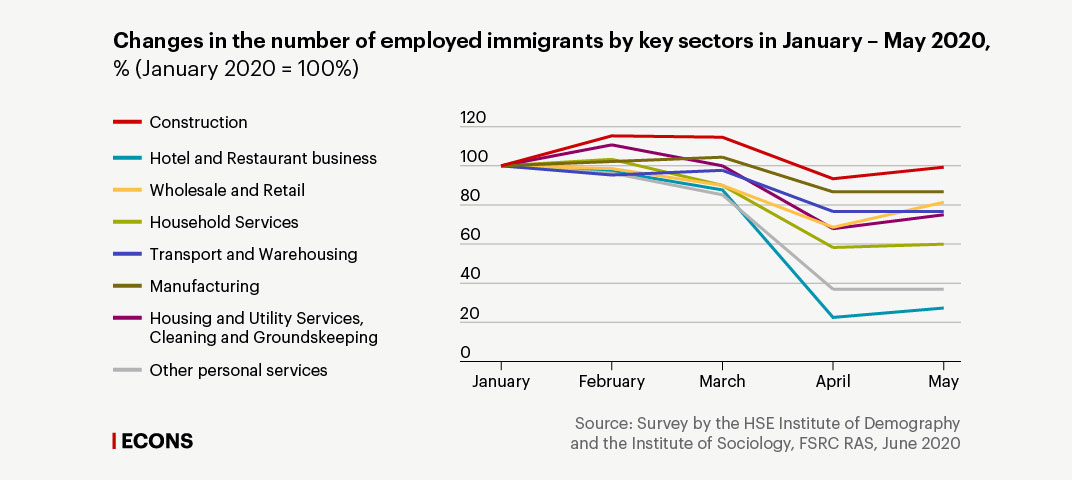

Not surprisingly, the hardest hit by the pandemic crisis were the hotel and restaurant sectors, where only 23.3% of migrant workers employed in February kept their jobs in the worst month of April, personal services (38.4% of February employees kept their jobs), household services (56.4%), and commerce (69.6%). To put this in perspective, 81% of February construction employees kept their jobs in April, and in May employment in this sector reached its January level (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Changes in the number of employed immigrants by key sectors in January – May 2020, % (January 2020 = 100%)

Construction

Hotel and Restaurant business

Wholesale and Retail

Household Services

Transport and Warehousing

Manufacturing

Housing and Utility Services, Cleaning and Groundskeeping

Other personal services

120

100

80

60

40

20

0

January

February

March

April

May

Source: Survey by the HSE Institute of Demography and the Institute of Sociology, FSRC RAS, June 2020

Construction

Hotel and Restaurant business

Wholesale and Retail

Household Services

Transport and Warehousing

Manufacturing

Housing and Utility Services, Cleaning and Groundskeeping

Other personal services

120

100

80

60

40

20

0

January

February

March

April

May

Source: Survey by the HSE Institute of Demography

and the Institute of Sociology, FSRC RAS, June 2020

Construction

Hotel and Restaurant business

Wholesale and Retail

Household Services

Transport and Warehousing

Manufacturing

Housing and Utility Services, Cleaning

and Groundskeeping

Other personal services

120

100

80

60

40

20

0

January

February

March

April

May

Source: Survey by the HSE Institute of Demography

and the Institute of Sociology, FSRC RAS, June 2020

Construction

Hotel and Restaurant business

Wholesale and Retail

Household Services

Transport and Warehousing

Manufacturing

Housing and Utility Services, Cleaning

and Groundskeeping

Other personal services

120

100

80

60

40

20

0

January

February

March

April

May

Source: Survey by the HSE Institute

of Demography and the Institute of Sociology,

FSRC RAS, June 2020

Lower qualified workers (CATI survey) are in a more dire state: in April, the most difficult month, only 40% of those employed in construction, commerce, and transport in February kept their jobs. Almost 10% of Russians employed prior to the lockdown lost their jobs when the self-isolation regime was introduced; among migrant workers, this share reaches 40-45%.

It seems that unlike Russian workers who have faced massive wage cuts, a common practice during the economic crises of the 2000s, immigrants have experienced massive layoffs due to business closures.

The most common reasons for job loss were business closures (31.5% of respondents) and staff redundancy (8.5%). It was extremely rare for employees to take the lead and leave on their own even when they were not paid (15.1%). It was quite often the case that enterprises did not operate during the lockdown and did not pay their employees but helped them in any way they could (for example, by providing food); in this case, people were registered as employees and waited for business to resume (18.9%).

People are more scared of being left with no money than of contracting COVID-19: those admitting to the former fear number three times as many as those fearing the latter. There is also COVID-dissidence coupled with chest-thumping: 16.7% are not afraid of either catching the coronavirus or being left with no money. The number of COVID-dissidents is even higher among CATI survey respondents, 23.4%, which suggests a higher prevalence of COVID-dissidence among less-educated immigrants.

Leave or stay

The overwhelming majority of respondents plan to work in Russia in 2020, including students, housewives, and retirees who have not previously participated in the labour market: 78.7% are confident in their plans to work in Russia, and a further 7.8% are considering this possibility.

The overwhelming majority of workers (78.4%) and job seekers (75.1%) are not thinking of leaving Russia in the upcoming months (at least until September-October), only one in ten is considering the possibility of returning to their country of origin for the time being and coming back to Russia when the situation clears up. Students, odd-jobbers, retirees, and housewives consider a temporary return to their home countries more often than others.

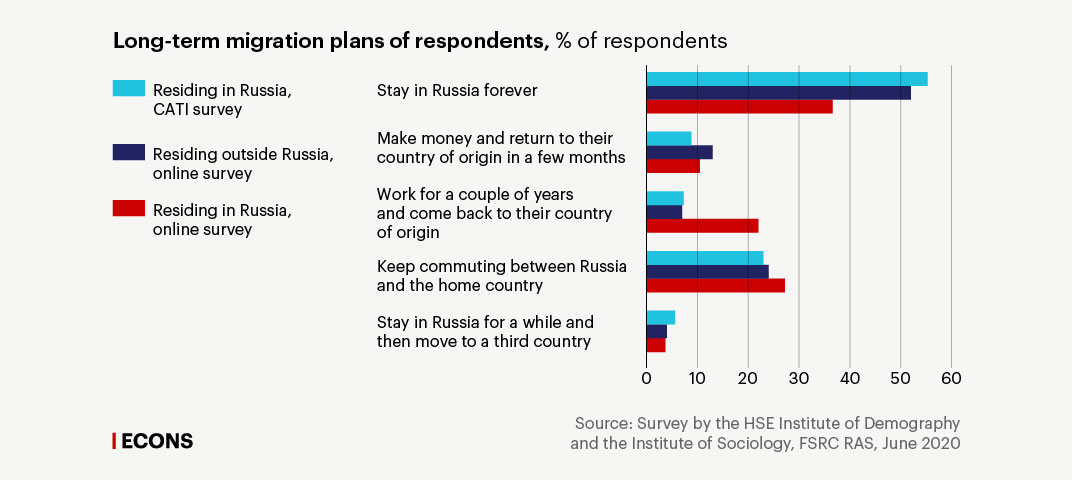

The majority of respondents are integrated in Russian society. They value their jobs in Russia and are afraid of losing them. The vast majority of them live in decent housing, most of them rent a separate apartment. It is of no surprise then that when asked about their long-term migration plans, the overwhelming majority say they intend either to stay in Russia forever or to reside there and visit their home countries from time to time.

In the country of origin

Russia’s lockdown and border closures were a great shock not only to those residing in Russia, but also to those planning to come here in spring and summer 2020. Our second online survey focused on the potential immigrants unable to enter Russia after international travel was suspended.

Its results indicate that the majority of migrant workers who returned to their countries of origin in 2020 were formerly employed in construction (more than 30%), the hotel and restaurant business (11%), commerce, and transport (8.2% each). However, in their home countries, the majority have faced the same problems as in Russia: employment opportunities have decreased significantly due to COVID-related restrictive measures. Only 40% of immigrants returning to their home countries worked in early June.

The majority of respondents link their prospects for improving their financial standing by working in Russia in one way or another: among respondents who worked or studied in Russia, 54% are planning to come to Russia for at least 3 months, and 11.4% - for less than 3 months. A little over 46% of respondents intend to come to Russia as soon as the borders open. At the time of the survey, respondents were optimistic about getting a job in Russia: a total of 67% of respondents were sure that they would find work quickly.

Migration potential

The CIS countries have amassed an enormous potential for migration to Russia due to shrinking labour markets and falling incomes among a significant part of the population during the corona crisis. This is demonstrated by both the unwillingness to leave Russia in the upcoming months expressed by migrant workers residing in Russia and the desire to come to work in Russia as soon as possible expressed by those residing in their countries of origin.

Potential migrant workers are frightened not so much by the coronavirus (one out of four is dismissive of the probability of falling ill) as by the prospect of being left with no money (40% of respondents). Migration intentions are particularly strong among those who have already worked in Russia fueled by a conviction that it is possible to find a job in Russia quickly.

The study has also shown that immigrants have quite a high potential for integration into Russian society (Figure 3). More than half of the respondents linked their future with Russia, expressing their intention to stay in Russia forever. Lower qualified workers from Central Asia (CATI survey) also expressed such plans. It is noteworthy that the majority share of such respondents among those residing outside Russia are Russians and Azerbaijanis (a little over 66%), while Belarusians are the minority (22%).

Figure 3. Long-term migration plans of respondents, % of respondents

Residing in Russia,

CATI survey

Residing outside Russia,

online survey

Residing in Russia,

online survey

Stay in Russia forever

Make money and return

to their country of origin

in a few months

Work for a couple of years and

come back to their country of origin

Keep commuting between

Russia and the home country

Stay in Russia for a while and

then move to a third country

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

Source: Survey by the HSE Institute of Demography and the Institute of Sociology, FSRC RAS, June 2020

Residing in Russia,

CATI survey

Residing outside Russia,

online survey

Residing in Russia,

online survey

Stay in Russia forever

Make money and return

to their country of origin

in a few months

Work for a couple of years and

come back to their country of origin

Keep commuting between

Russia and the home country

Stay in Russia for a while and

then move to a third country

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

Source: Survey by the HSE Institute of Demography

and the Institute of Sociology, FSRC RAS, June 2020

Residing in Russia, CATI survey

Residing outside Russia, online survey

Residing in Russia, online survey

Stay in Russia forever

55,3

52,0

36,6

Make money and return to their country of origin

in a few months

8,8

13,1

10,5

Work for a couple of years and come back

to their country of origin

7,3

7,2

22,0

Keep commuting between Russia and the home country

23,0

24,0

27,2

Stay in Russia for a while and then move

to a third country

5,6

3,7

3,7

Source: Survey by the HSE Institute of Demography

and the Institute of Sociology, FSRC RAS, June 2020

Residing in Russia, CATI survey

Residing outside Russia, online survey

Residing in Russia, online survey

Stay in Russia forever

55,3

52,0

36,6

Make money and return to their country

of origin in a few months

8,8

13,1

10,5

Work for a couple of years and come back

to their country of origin

7,3

7,2

22,0

Keep commuting between Russia

and the home country

23,0

24,0

27,2

Stay in Russia for a while and then move

to a third country

5,6

3,7

3,7

Source: Survey by the HSE Institute

of Demography and the Institute of Sociology,

FSRC RAS, June 2020

During the previous economic crises, the decrease in the number of labour immigrants was strongly dependent on the economic situation. Now it is completely different: the prevailing factors are those pushing potential immigrants from their countries of origin to the Russian labour market.

Migrant workers residing in Russia do not intend to leave the country, and those who wanted to return to their home countries and stay there until autumn when things clear up but did not manage to leave are becoming less motivated to leave Russia with each passing day due to the travel suspension. At the same time, the number of potential migrant workers in source countries keeps increasing, reaching alarming proportions. The data provided by the Border Service of the Federal Security Service for 2019 gives an idea of the scale of this phenomenon: in April - June at least 1.5 million foreigners arrived in Russia for work purposes. About the same number of immigrants would have arrived in Russia during this period of 2020 but for the pandemic.

A blow for the economy of the CIS countries

In July, Russia extended the ban on international travel until August 1. If prolonged further, it will hinder the massive autumn influx of migrant workers when thousands of graduates unable to find jobs in their home countries enter the Russian labour market.

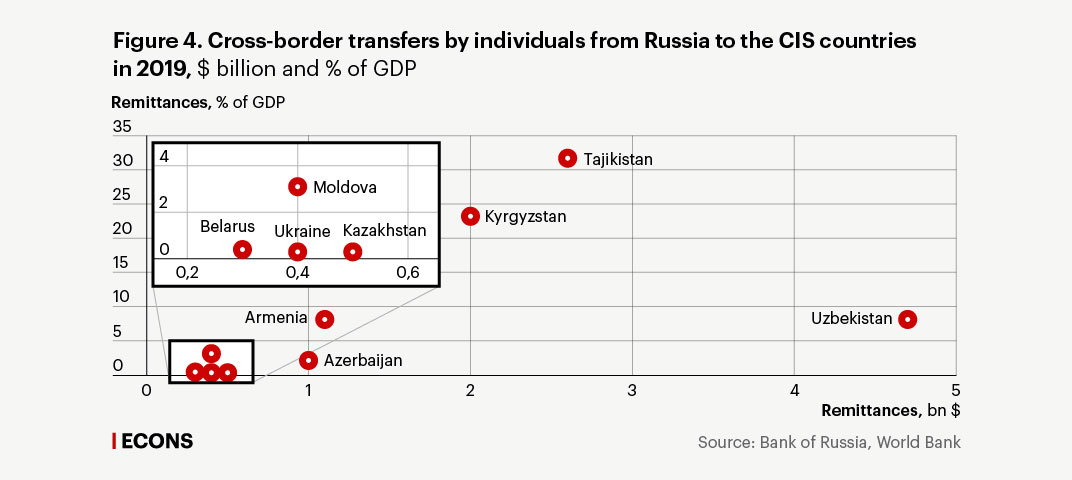

The source countries will suffer considerable losses from the decreased flow of migrant workers, especially those countries where migrant remittances from Russia constitute a significant amount relative to GDP (Armenia, Kirghizia, Tajikistan). According to our estimates based on the data provided by the Bank of Russia and the World Bank statistics, if Russia’s entry ban persists, the number of migrant remittances received by the CIS countries may fall by 30% in 2020 compared to 2019, which will have a significant effect on the welfare of those who live there and the stability of these countries’ financial systems, and will decrease investments in their economies.

Migration is of great importance to the source countries. Labour migration alleviates pressure on the labour markets of the countries where the number of youth is growing rapidly (Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan) or where the labour market is 'shrinking' (Armenia, Moldova, Ukraine). For example, in 2019, 47% of Tajikistan's workforce participated in labour migration, in Kyrgyzstan this figure was at least 17.5%, in Armenia – at least 16%, in Uzbekistan, 14%. Although some labour migration flows from Ukraine and Moldova are shifting to Europe, Russia is still one of the key migration destinations for these countries.

The major source countries receive significant migrant remittances from Russia (see Figure 4). They increase household consumption and reduce poverty and, thus, constitute an important source of financing for certain sectors of the economy and a major source of foreign currency inflow, exceeding foreign direct investments in the economy of these countries.

Figure 4. Cross-border transfers by individuals from Russia to the CIS countries in 2019, $ billion and % of GDP

Remittances, % of GDP

35

4

Tajikistan

30

3

Moldova

25

2

Kyrgyzstan

1

20

Belarus

Ukraine

Kazakhstan

0

0,2

0,3

0,4

0,5

0,6

15

10

Armenia

Uzbekistan

5

Azerbaijan

0

0

1

2

3

4

5

Remittances, bn $

Source: Bank of Russia, World Bank

Remittances, % of GDP

35

4

Tajikistan

30

Moldova

3

25

2

Kyrgyzstan

Belarus

1

20

Ukraine

Kazakhstan

0

15

0,2

0,3

0,4

0,5

0,6

10

Armenia

Uzbekistan

5

Azerbaijan

0

0

1

2

3

4

5

Remittances, bn $

Source: Bank of Russia, World Bank

Remittances,

% of GDP

Remittances,

bn $

Tajikistan

Kyrgyzstan

Uzbekistan

Armenia

Moldova

Azerbaijan

Belarus

Kazakhstan

Ukraine

0

10

20

30

40

0

1

2

3

4

5

Source: Bank of Russia,

World Bank

Remittances,

% of GDP

Remittances,

bn $

Tajikistan

Kyrgyzstan

Uzbekistan

Armenia

Moldova

Azerbaijan

Belarus

Kazakhstan

Ukraine

0

10

20

30

40

0

1

2

3

4

5

Source: Bank of Russia,

World Bank

A shortage of hands

The bad news for Russia is that the corona crisis has caused a shortage of low- and semi-skilled workers in construction, commerce, transport and warehousing, as well as semi- and high-skilled workers in household and personal service sectors where the share of labour costs is highest and the role of migrant workers is particularly significant.

This was already somewhat noticeable in the trough of the crisis: in transport and warehousing sectors as well as in household services and construction, the wages of migrant respondents increased by 10%, 4.8%, and 2.9% respectively in April compared to the peak of February. Rosstat says the same: in February and April, average wages paid to Russians increased by 10.3% in transportation and warehousing sectors and by 0.8% in construction. This means that, on the one hand, some ‘migrant’ jobs can be taken by Russians, both locals, and domestic migrants. On the other hand, prices for the goods and services in the sectors where immigrants play or used to play an important role will inevitably increase.

Against the backdrop of the economic slump and reduced demand for labour, a decreased supply of foreign labour seems natural and predictable in Russia, as in other countries. However, the shortage of migrant workers in regions and industries with a high concentration of immigrants may hinder economic recovery. Russia's post-corona economy needs immigrants just as much as it needed them in the pre-pandemic past.