For more than two decades, economists have been discussing a rise in the retirement age in Russia with diligence equaled only by the fruitlessness of the debate. Last year, this state of affairs was turned on its head when a decision to abruptly increase the retirement age to 65 for men and 60 for women was taken in very little time and with next to no expert discussion. This article attempts to reach a (retrospective) understanding of this most recent stage of pension reform.

The pension trilemma

We begin by defining the range of options, which were realistically available to the government when choosing its pension strategy for the upcoming presidential term: after all, there is no sense in evaluating the strategy the government chose without also considering alternatives to it.

In the 21st century, the main risk to the stability of pension systems is population ageing, i.e. changes in the ratio of the retired population to the working-age population (the dependency ratio). It is clear enough that the three key indicators of this phenomenon are related and fundamentally identical: (a) the replacement ratio (the size of the average pension vs. the average pre-retirement income), (b) the proportion of GDP the state spends on pensions, and (c) the ratio of retirees to people in work. A higher dependency ratio inevitably causes (c) to increase, thereby making it impossible to maintain the status quo.

By analogy with the well-known Mundell–Fleming trilemma, which postulates the incompatibility of three elements of monetary policy – the free flow of capital, a fixed exchange rate, and monetary autonomy – we can formulate a “pension trilemma”: an ageing population makes it impossible to maintain a stable replacement ratio, stable expenditure on state pensions, and a stable retirement age. An increasing dependency ratio forces the government to adapt the pension system to the imbalances which have appeared in one of three ways: by increasing spending on state pensions, by decreasing the replacement ratio, or by raising the effective retirement age (by changing the standard retirement age and/or by imposing stricter conditions on early retirement).

The government’s choice of strategy is likely to depend on the results of numerous models of alternative strategies for adapting to population ageing, among other factors. The conclusions of these models are surprisingly similar and can be simply summarized as follows:

- A greater proportion of elderly people in the population causes significant economic slowdown (primarily due to a shrinking workforce).

-

Raising the retirement age partially offsets the negative effect of population ageing.

-

Increasing the retirement age is the best possible strategy for adapting to population ageing in terms of GDP growth and public welfare.

-

Under quite natural assumptions, the optimal retirement age varies with life expectancy.

David Bloom et al. provide an interesting addition to this point. They highlight that household income per capita increases in parallel with life expectancy, making leisure preferable to consumption, which reduces the optimal retirement age and replacement ratio in a lifecycle. These two trends combined result in the optimal retirement age increasing a little slower than life expectancy.

Analysing how the world adapts to population ageing in actual fact (see, for instance, a report by the IMF, a report by the European Commission), we can conclude that, in recent years, it has been combining several strategies: primarily increasing the retirement age and decreasing the replacement ratio. At the same time, countries in which expenditure on state pensions exceeds a threshold level (about 11% of GDP for the EU) tend to start reducing this expenditure. There seems to exist a natural limit for spending on state pensions beyond which expenditure has to be cut back.

The cost of postponing reform

Russia has also used all these methods of adaptation, but one at a time rather than simultaneously.

From 2002 until 2007, the balance was maintained entirely by reducing the replacement ratio. Despite the rapid increase in the size of pensions, the government seems to have considered further widening of the gap between the incomes of pensioners and the employed unacceptable from a social and political perspective, therefore making a dramatic shift to another pension policy. The replacement ratio was increased from 23% to 34% and stayed at this level until 2017.

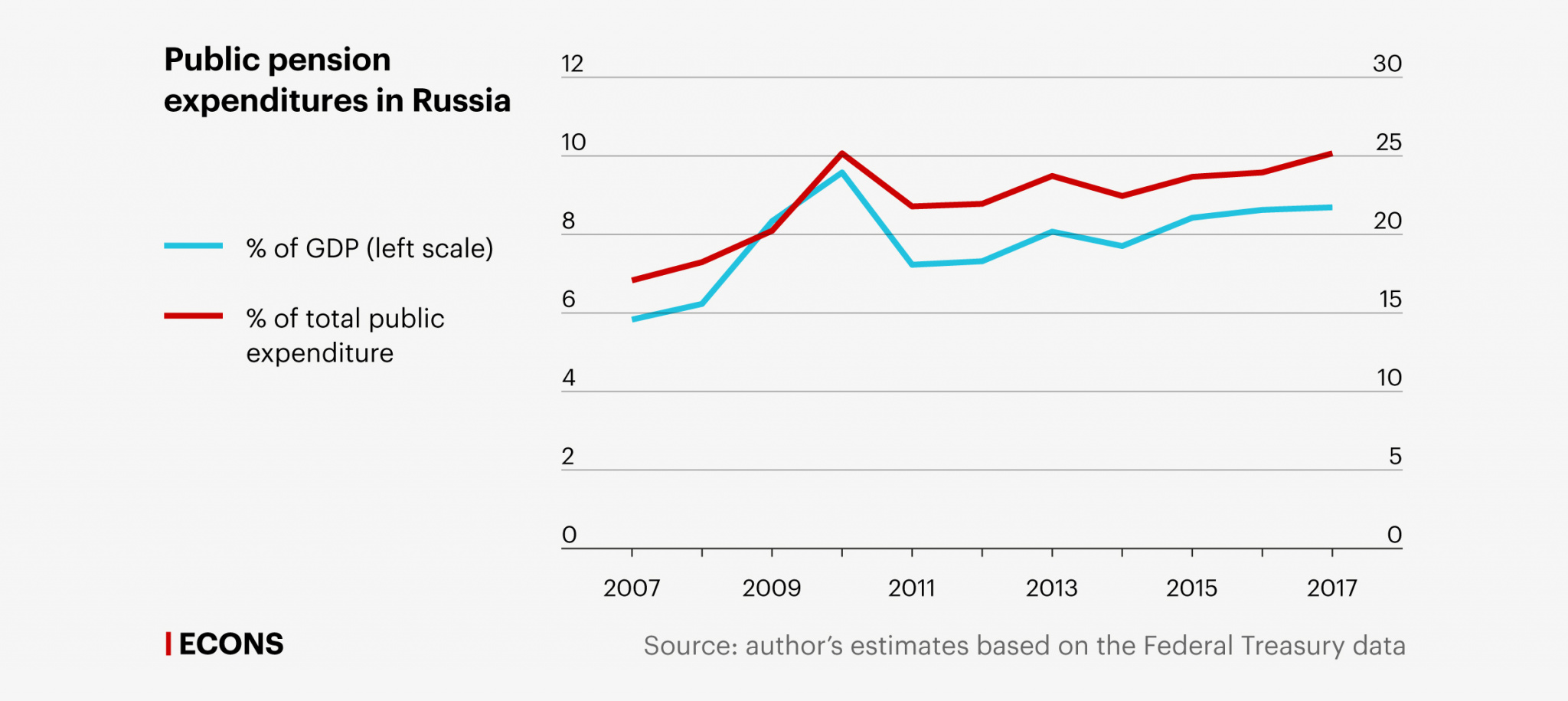

This policy required higher spending on state pensions (Chart 1). Over a decade (in 2017 compared to 2007), public spending on pensions grew by 50% as a proportion of both GDP (increasing from 5.9% to 8.7%) and total public expenditure (from 17% to 25%). Contrary to common belief, the government was not cutting back on pensions: in fact, they were the main priority, encroaching upon all other expenditure, particularly on education (public spending on education fell by 0.5% of GDP), healthcare, and sport (spending on which decreased by 0.8% of GDP).

Overall, analysis shows that two-thirds of the total increase in spending on state pensions (almost 3% of GDP) was attributable to a decrease in other expenditure, largely ‘productive’ (i.e. growth-enhancing) spending, while the other third was financed by increasing the effective pension contribution rate (employees paying labour taxes means redistribution from the workforce to pensioners).

This policy can hardly be considered reasonable. Firstly, higher pension contributions decrease the labour supply, which is already insufficient as things stand. Secondly, relatively speaking, our government spends a great deal on pensions (twice as much as other similar economies and even more than OECD countries on average), while many important sectors, such as healthcare, receive much less public funding than international standards require. That healthcare is currently underfunded is becoming ever more obvious.

In short, in different periods, Russia has used two different strategies for adapting to population ageing, which have now exhausted their usefulness. Therefore, a rise in the retirement age was both strategically inevitable (there was no real alternative) and the best possible option in terms of long-term economic prospects and public welfare.

Chart 1. Expenditure on state pensions in Russia

% of GDP (left scale)

% of total public expenditure

12

30

10

25

8

20

6

15

4

10

2

5

0

0

2007

2008

2009

2010

2011

2012

2013

2014

2015

2016

2017

Source: author’s estimates based on the Federal Treasury data

% of GDP (left scale)

% of total public expenditure

12

30

10

25

8

20

6

15

4

10

2

5

0

0

2007

2008

2009

2010

2011

2012

2013

2014

2015

2016

2017

Source: author’s estimates based on the Federal Treasury data

% of GDP (left scale)

% of total public expenditure

12

30

10

25

8

20

6

15

4

10

2

5

0

0

2007

2009

2011

2013

2015

2017

Source: author’s estimates

based on the Federal

Treasury data

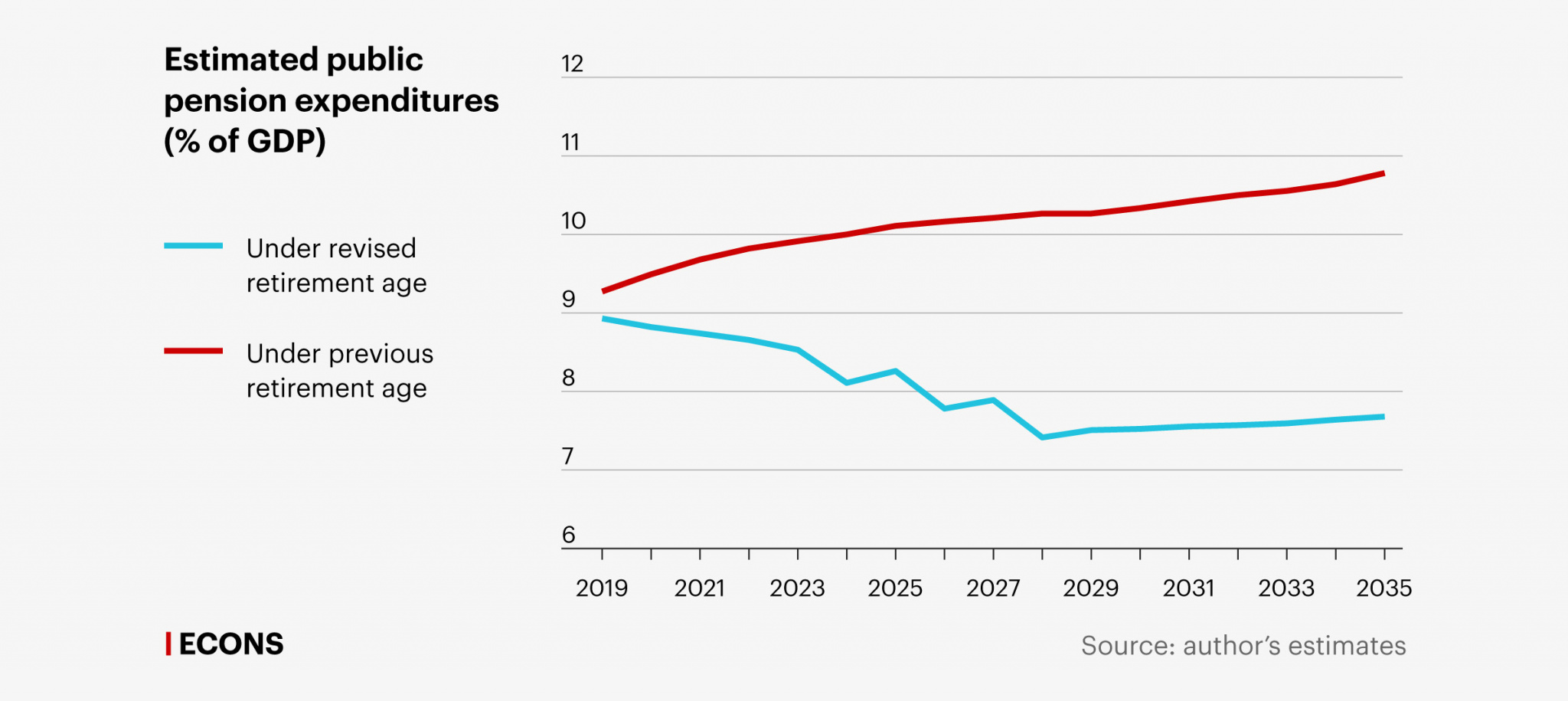

Who will gain

How can we estimate how much the budget will gain from the increased retirement age? The first step is to calculate spending on state pensions under the previous retirement age and the increased retirement age, assuming that the replacement ratio remains 34% (Chart 2). The fiscal effect of an increase in the retirement age can be estimated in two ways:

1. As the difference between estimated spending on state pensions under the previous retirement age and the revised retirement age.

2. As the difference between estimated future spending on pensions and real expenditure on pensions before the reform.

The first of these methods is partly hypothetical, as it shows how much public money would be saved if spending on pensions were to have continued increasing at its previous rate. The second method shows how much money is actually available (assuming public income remains stable).

Chart 2. Estimated expenditure on state pensions (% of GDP)

Under revised retirement age

Under previous retirement age

12

11

10

9

8

7

6

2019

2020

2021

2022

2023

2024

2025

2026

2027

2028

2029

2030

2031

2032

2033

2034

2035

Source: author’s estimates

Under revised

retirement age

Under previous

retirement age

12

11

10

9

8

7

6

2019

2021

2023

2025

2027

2029

2031

2033

2035

Source: author’s estimates

Under revised retirement age

Under previous retirement age

12

11

10

9

8

7

6

2019

2023

2027

2031

2035

Source: author’s estimates

Chart 2 shows that the effect of an increase in the retirement age estimated using the first method reaches 3% of GDP by 2033 and then continues slowly increasing. In this case, a higher retirement age enables pensions to be kept stable while public spending is significantly reduced (by 3% of GDP). In this case, the main result is a cap on public spending growth.

When estimated using the second method, the effect of the reform is much smaller: public pension expenditures reach their minimum in 2028 compared to 2017 (having decreased by 1.3% of GDP), after which the effect gradually fades.

The most reasonable strategy would seem to be to allocate the public money saved to improving the health of Russia’s citizens and increasing their healthy life expectancy. Our analysis shows that the revised retirement age is underestimated for women and overestimated for men (demographic trends would suggest an optimal retirement age of 62 for women and 63 for men). A public programme should be launched aimed at protecting men’s health, including through the active promotion of healthy lifestyles, in order to bring their healthy life expectancy in line with the retirement age, since the latter was revised without regard to demographic trends.

The full text of this article is published in the journal Voprosy Ekonomiki, No 9 (2019).