Direct Quantitative Restrictions: Why Limit High-Risk Loans?

With this publication, my colleagues from the Financial Stability Department and I are beginning to run our new blog, PROstability. In this blog we will regularly share our thoughts and ideas on the most relevant and debating issues of financial stability, so that everyone interested in this topic can join in the discussion on this website (you can leave comments on publications) or on others.

We begin with direct quantitative restrictions, or macroprudential limits as these restrictions may be renamed after the second reading of the bill on this instrument (link in Russian) in the lower house of the Russian parliament. On October 21 the bill was adopted at the first reading.

The easiest way to define financial stability is through its absence. Financial or banking crises are events that are impossible to miss. They hit both people and the economy hard. Therefore, it is important for regulators to identify the vulnerabilities of the financial system to shocks and risks in advance, to apply measures to reduce such vulnerabilities and to prepare instruments to mitigate should the risks materialise.

Both unsecured and mortgage lending to individuals, especially in the context of mainstream use of residential property as an investment object, are typical areas for the formation of financial market bubbles. At the stage of lending growth, involving an ever greater number of people in the process and increasing their debt burden, problems do not immediately become apparent. But when the bubble inflates to critical levels, problems begin to arise ever more rapidly, which leads to a crisis.

The Bank of Russia has already encountered such situations and has created a toolkit to mitigate the risks. For example, we have the opportunity to discourage the issuance of unsecured loans to borrowers with a high debt burden or with a high effective interest rate by increasing the capital requirements of banks (risk weights add-ons in calculating the capital adequacy ratio) for loans with a high debt burden. In mortgages such restrictions are possible on loans with low down payments. Simply put, our regulations force banks to set aside more of their own capital in order to cover future losses on such loans.

This measure works effectively as a tool to reduce the risks of banks in the event that borrowers begin to experience problems en masse. Last year's (2020) example demonstrates this clearly. When borrowers began to apply en masse for credit holidays and loan restructuring, the Bank of Russia released macroprudential buffers, that is, gave banks the opportunity to use the previously accumulated "nest egg" to cover losses on problem loans and issue new ones. The existence of such "nest eggs", or buffers, was one of the factors that helped banks to cope with the situation.

On the other hand, as practice has shown, these measures have limited effectiveness when we need to slow down (link in Russian) the growth of high-risk forms of lending. The need to fill buffers limits the ability to issue new high-risk loans mainly for banks with a small capital reserve - it is difficult for them to freeze part of their own capital to cover high-risk loans. Banks with a large capital reserve, however, are far less sensitive to such measures, especially given the fact that consumer lending generates high income for them, which covers the increased requirements on capital.

Therefore, as a result of the increase in risk weights add-ons, banks with a small capital reserve may slow down the issuing of high-risk loans and move partially into slightly lower risk areas, but their market share may be hogged by banks with high capital reserves. This is exactly the situation we see now. The group of banks which accounts for 20% of the market provides 40% of the growth in the portfolio of consumer lending.

Around the world a common way of dealing with the buildup of vulnerability in this area is direct quantitative restrictions, or macroprudential limits. These measures limit the share of high-risk loans in new lending by banks. First and foremost this means loans with a high level of debt burden on the borrower, for example loans with a debt service to income (DSTI) of more than 80% (where borrowers spend more than 80% of their income on servicing their debt) or long-term (more than 5 years) unsecured loans. It is precisely on the proportion of such loans in new lending that the Bank of Russia is going to impose restrictions.

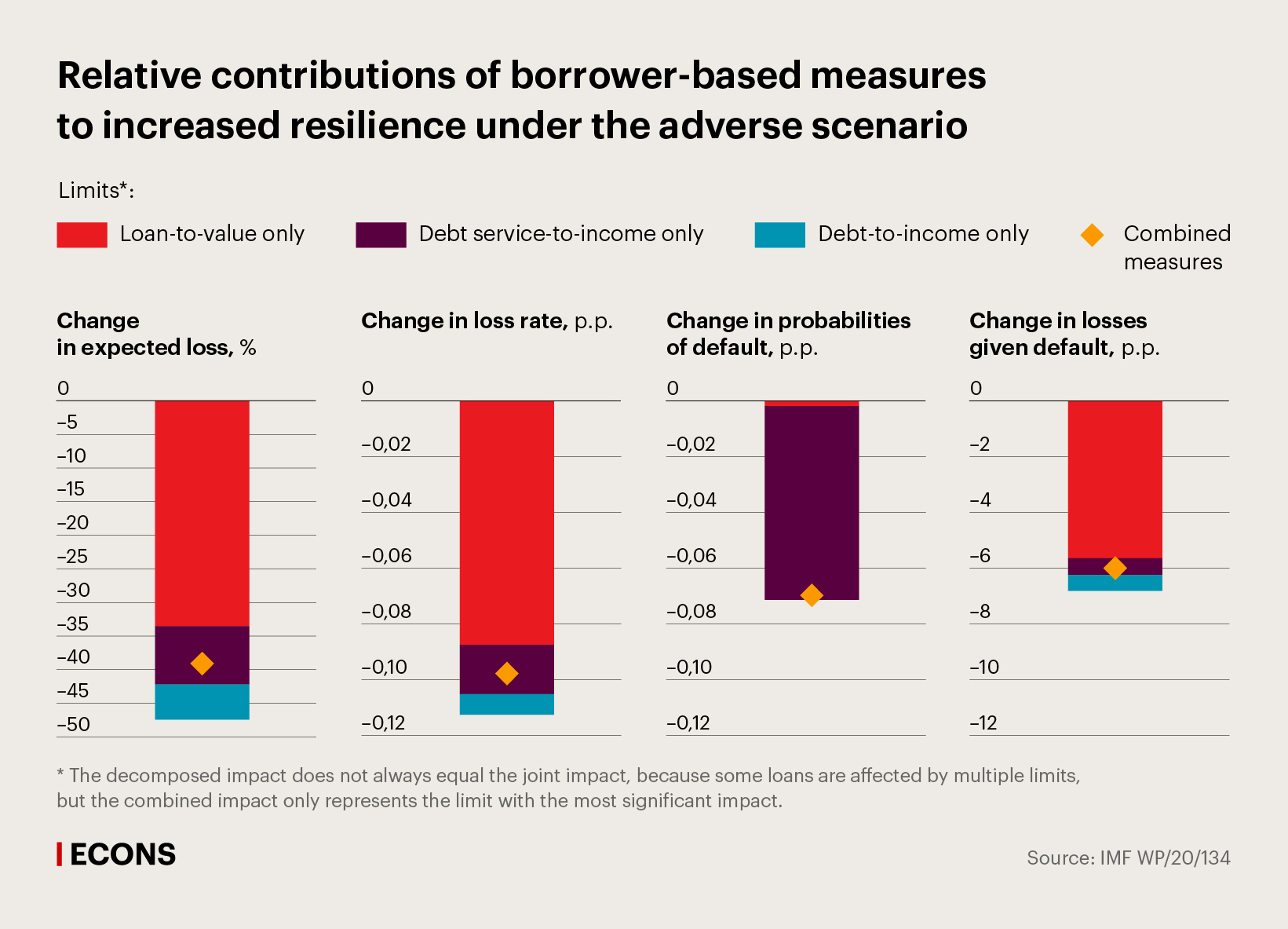

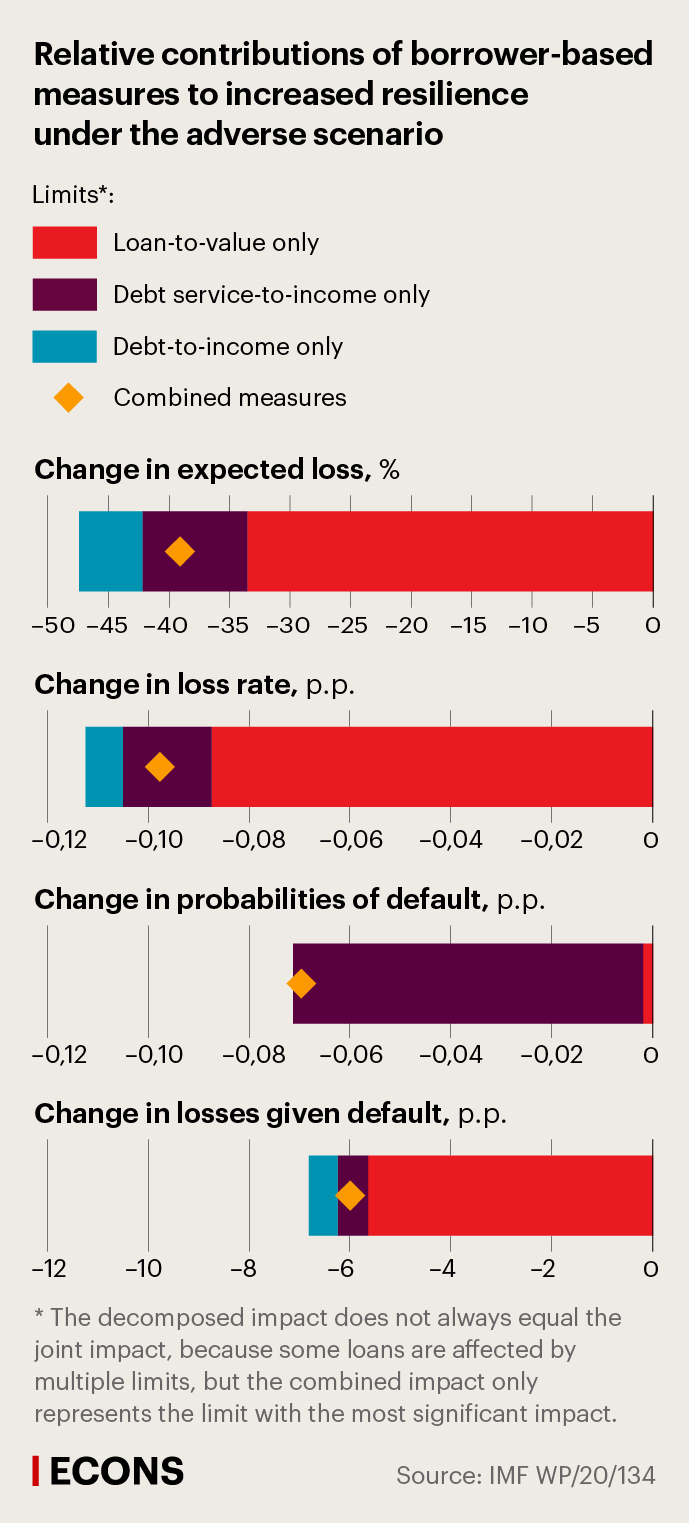

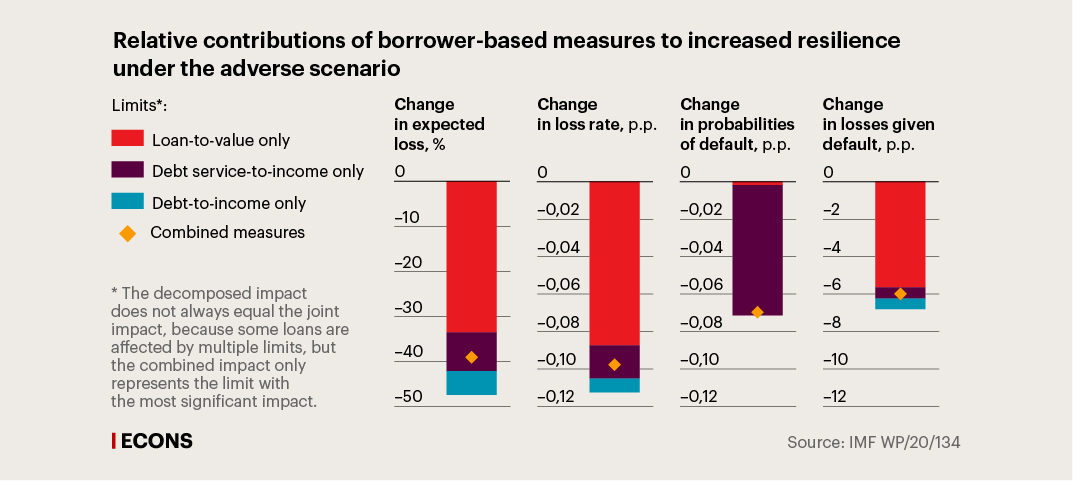

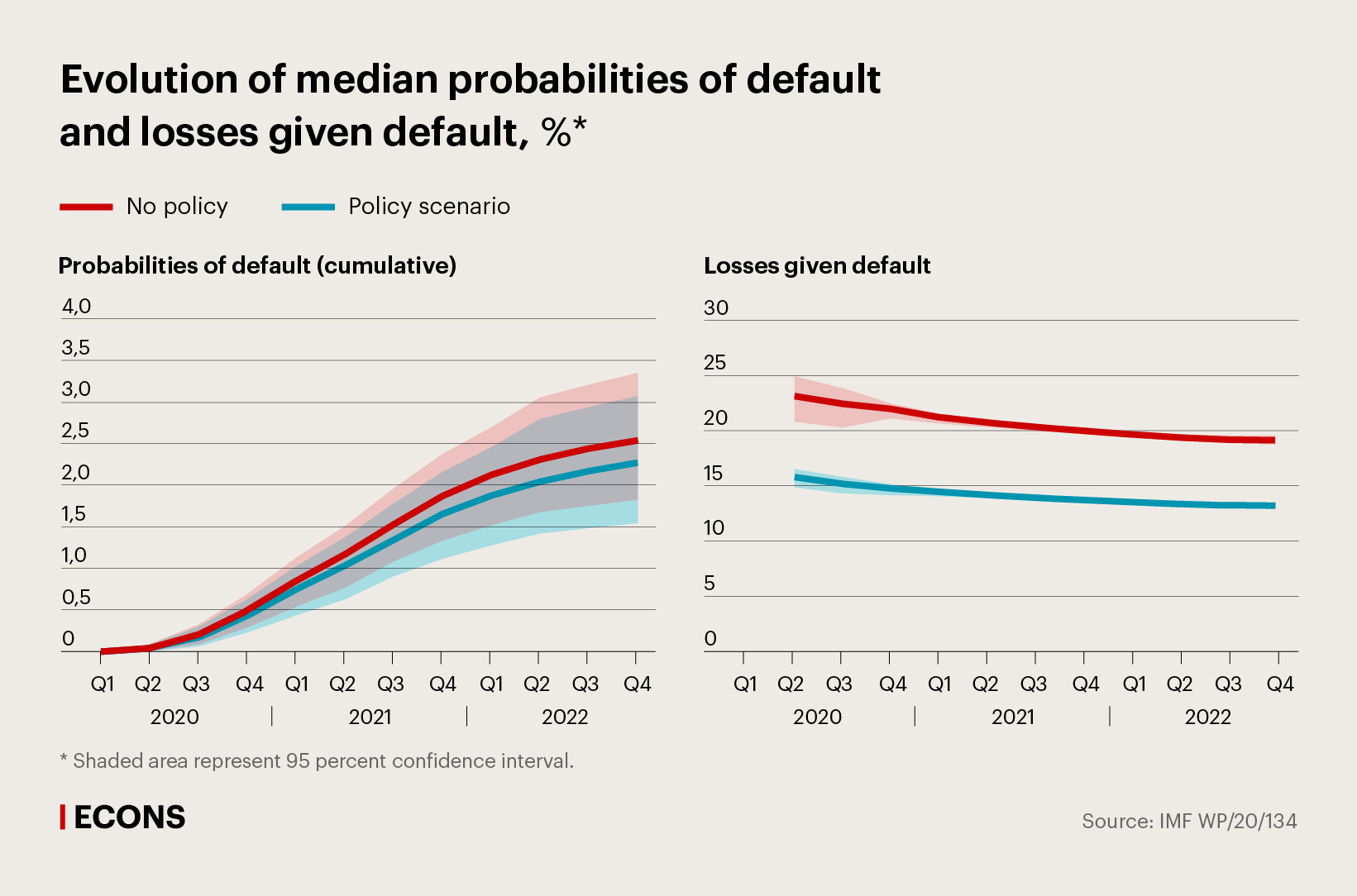

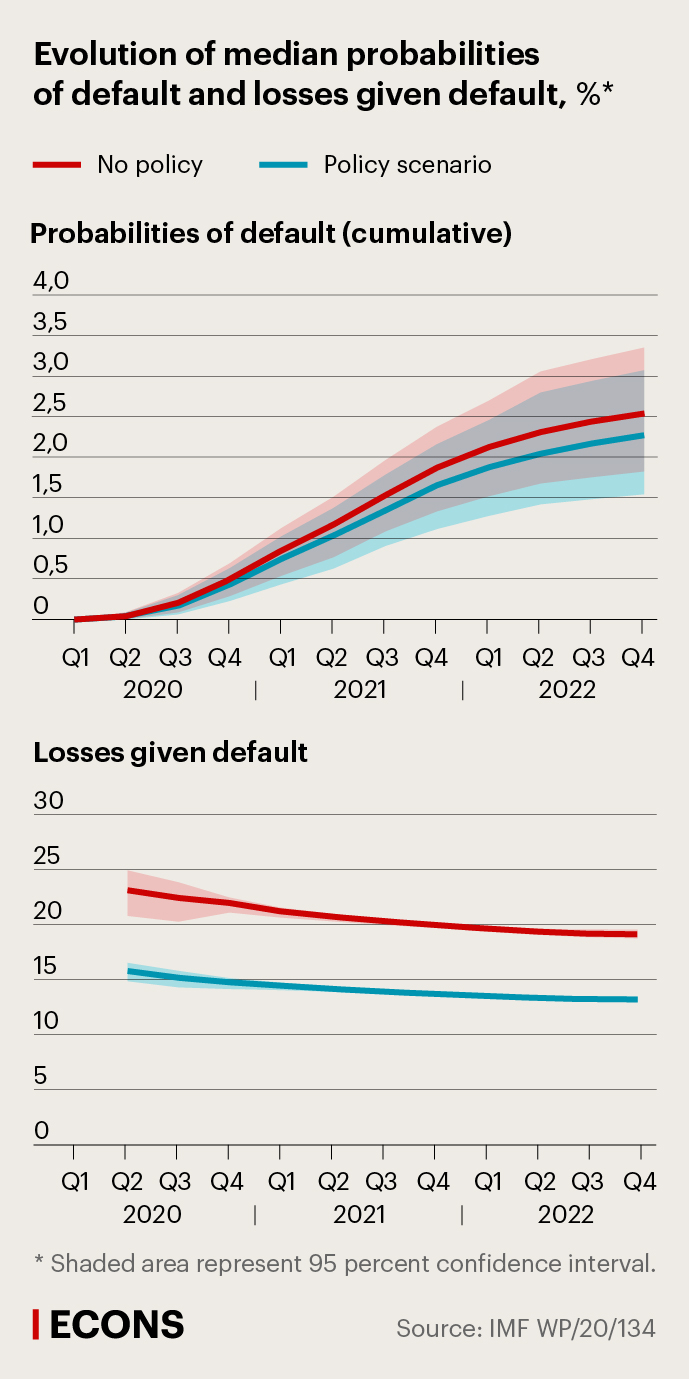

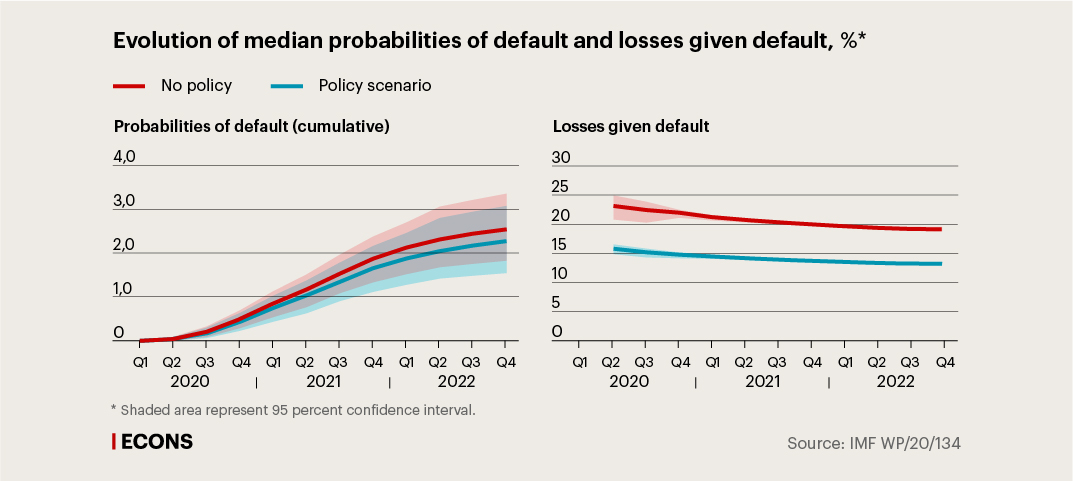

What effect this has is clearly seen from the results of a study by IMF experts. The researchers used detailed data from surveys of households in Slovakia to build a simulation model of the Slovakian mortgage market. With its help they assessed the impact of direct quantitative restrictions on the market since 2014. The model enables the construction of a scenario of market development in which such measures had not been introduced and to compare it to the scenario where they had been introduced. Quantitative restrictions during this period were set on the down payment, debt servicing ratio and the ratio of total debt to income. The results of simulation experiments show that restrictions on the size of a loan or loan installments in relation to income significantly reduce the likelihood of default, and restrictions on the minimum amount of the down payment reduce default losses.

These measures contribute to a greater concentration of activity on low-risk loans, cooling the lending growth rates themselves slightly. For the banks, the reduction in income from the slowdown in lending growth is offset by an improvement in the quality of the loans. Finally, from a macroeconomic point of view, such measures dampen the fluctuations in the economy between periods of growth and periods of recession.

There are similar studies based on data from other countries. In particular, European appraisals are more broadly presented in a study by the European Central Bank. I would like to note that, compared to the risk weights add-ons already used in Russia, direct quantitative restrictions (macroprudential limits) have the same effect on the policies of banks, regardless of the size of their capital reserves, and of micro-finance companies, which can have a positive effect on competition. And just as importantly, they do not take capital from other forms of lending. That is why we believe that in a wide range of situations, in order to prevent the buildup of vulnerability to risks in the financial system, we need to use direct quantitative restrictions.

Many people ask how this measure will affect financial availability in an environment where the methods of obtaining information on income and the tools for measuring income used by banks to calculate the debt burden are imperfect. That is why we do not plan to introduce hard-and-fast quantitative limits and intend to regulate only the proportion of high-risk loans, allowing banks to use these limits to lend to those whose risks, according to the bank, are lower. In all other situations, you need to understand that a loan is an opportunity to increase consumption today at the expense of reducing it tomorrow and for the entire period of loan repayments. Therefore, if the repayment burden turns out to be high, then, of course, it makes sense to think about whether it is worth so limiting your future consumption, or whether it would be better to postpone the purchase. If a person already has a high debt burden, then new loans will only increase the problems and will not help to solve them. The law (link in Russian) will help potential borrowers to correctly assess their risks obliging banks to inform clients about their future debt burden if, upon receiving a new loan, repayments on all debts exceed 50% of their income.

.jpg)