Over the last 25 years, the growth of the Russian economy has been extremely uneven: GDP almost doubled from 1999 to 2008, followed by a period of stagnation, with growth of only 16% between 2009 and 2021. The previous favourable factors that provided high rates of economic growth have been broadly exhausted. The search for new sources of growth prompted interest in human capital, the significance of which had received wide recognition (link in Russian) by then.

Human capital includes the expertise and skills of workers that affect their labour productivity. It is created through parents investing in the development of their children, by further formal education, by advanced training, by on-the-job training, by investment in health, and even by workers’ personal qualities. In addition to accumulation, human capital is also subject to depreciation, i.e., the loss of existing abilities and skills or their loss of relevance to the economy. At the same time, the availability of human capital is not a guarantee that all of it will be used efficiently and be able to influence the economic growth rate.

However, an attempt to assess the dynamics of human capital, taking into account the variety of processes and factors influencing it described above, is inevitably hampered by a significant lack of data. Researchers have to use the approximating indicators that are available, at best seeking to take all the information on hand into account as much as possible. To assess the dynamics of human capital in Russia, I limited myself to data on the duration of formal education and the health of Russian workers. To capture the relationship between these indicators and productivity, I included microeconomic estimates of the return on the corresponding investments in my calculations. Thus, I used a human capital index that characterises workers’ productivity in connection with their education and health. This approach adapts the World Bank's methods to the assessment of the dynamics of human capital and to Russian statistics.

All existing papers, including Russian microeconomic research, provide more data on the various aspects of the accumulation and depreciation of human capital than the index I proposed. The lack of quality data on the results of the assessment of adult cognitive skills, which are a direct reflection of the knowledge and skills of those employed in production, is still a significant limitation. At the same time, the index used shows the changes in the key forms of human capital, which are also closely linked to other productivity characteristics of workers and which underpin further investments in human capital.

In assessing the contribution of human capital to the growth of the Russian economy, I employed the standard approach based on growth accounting. Therefore, I explored only the direct channel of human capital's impact on economic growth, which is directly related to the increase in labour productivity. However, the list of these channels is much broader, namely the role of human capital in generating new knowledge and technologies, in their further integration and distribution, in the making of investment decisions by companies, etc.

How and why the impact of human capital changed

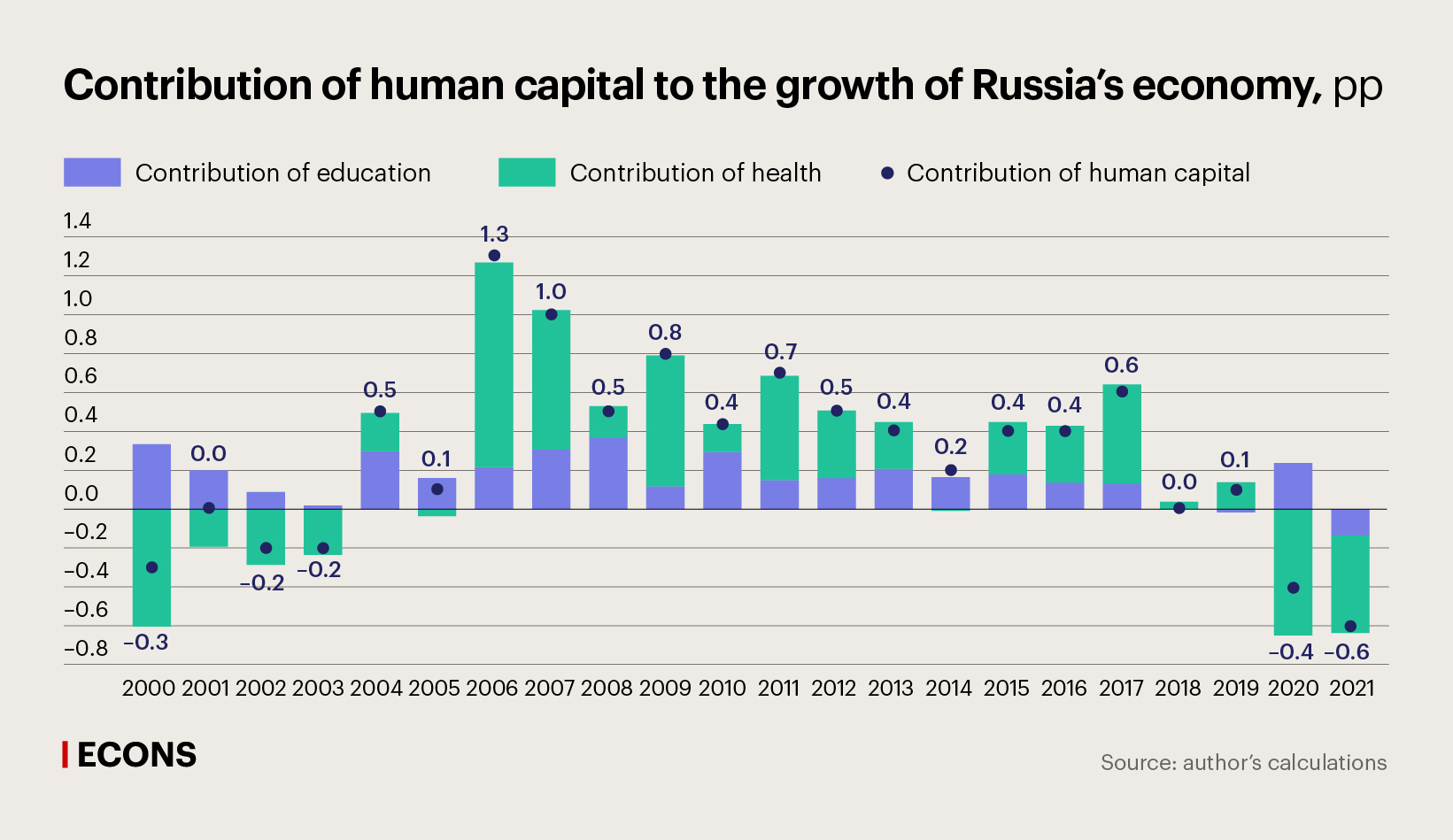

According to the estimates (see the chart below), the main period in which human capital made a positive contribution to Russian economic growth was between 2004 and 2017, when increasing education levels and the improving health of workers ensured annual economic growth of approximately +0.6 percentage points (pp). However, despite the substantial contribution, especially in particular years, increased human capital accounts for only around 15% of the economic growth in this period.

The contribution of human capital peaked in the second half of the 2000s. The preceding period of strong economic growth provided incentives and opportunities for boosting human capital, i.e., for investing in knowledge, skills, and health. Large younger generations were entering the labour market, and an increasing proportion of them opted for higher education.

In addition, the high dynamics of human capital indicators (education, health) during that time were partly explained by the low base effect. For example, the lifting of the administrative restrictions of the planned economy highlighted a considerable unrealised demand for vocational training, while the high potential for improving the health of the population is largely attributable to the long period of increasing mortality following the series of crises in the 1990s.

However, the growth rates of human capital indicators (which underlie the dynamics of its contribution to economic growth) started to slow down over time. For example, while in 2006–2009, the average annual contribution of human capital to economic growth was 0.9 pp, in 2010–2013, it was already 0.5 pp, and it fell to a mere 0.4 pp over 2014–2017.

The inflow of younger generations into the labour market decreased substantially in the 2010s under the influence of demographic factors, the rate of renewal of human capital in the form of education, which had already become quite high, also slowed down. The opportunities for investment in human capital contracted due to the decelerated growth of real disposable income after the global crisis, followed by a decline in incomes since 2014. Resources for education became limited, and further improvement in the health indicators began to require more decisive transformations in healthcare. As a result, the average annual contribution of human capital to economic growth approached zero in 2018–2019.

However, it should be borne in mind that there are natural limits to the potential for increasing worker productivity through formal training and improving health. It is likely that, by that time, the main potential for further productivity dynamics was centred around improving the quality of the knowledge and skills of Russian workers, which would have been accounted for by assessments of adult cognitive skills. In addition, the accumulated stock of human capital continued to influence economic growth through indirect channels, the role of which is not evaluated in my study.

In 2020–2021, the contribution of human capital to the growth of the Russian economy dropped to -0.5 pp due to the significant deterioration of the population’s health during the COVID-19 crisis. However, this negative contribution signifies the negative impact of the pandemic on the health and productivity of workers and thus on the economic growth rate, rather than that human capital played a negative role for the economy.

The transformation of the Russian economy, which began in 2022, raises the question of the prospects for human capital dynamics, with papers (link in Russian) exploring this topic only just starting to appear.

The full text of the study is published in the HSE Economic Journal, 2024, Vol. 28, No. 1.