Fear of Forward Guidance

Monetary policy is invariably conservative. Before adopting new approaches and ideas, central banks subject them to careful inspection, scrutiny, and testing. In the early 1990s, debate regarding the suitability of flexible (and, ultimately, floating) exchange rate arrangements for emerging markets was in full swing; today, floating exchange rates and inflation targeting regimes are the most widespread and widely preferred monetary approaches. Even once the advantages of a flexible exchange rate had become almost universally apparent , the monetary authorities released their grip on the FX market only with great caution. Guillermo Calvo and Carmen Reinhart call this ‘ fear of floating’. This phenomenon manifests itself in the gap between the professed and the actual flexibility of the exchange rate arrangement.

We believe that central banks are similarly cautious when it comes to the adoption of new ideas, particularly of transparent monetary policy, including forward guidance. Just like ‘fear of floating’, ‘fear of forward guidance’ is generated by potential inconsistency – in this case, between the professed transparency of communication and the amount of information on future policies the central bank actually discloses.

The effectiveness of monetary policy is largely determined by clear communication of a central bank’s intentions, as is highlighted by the authors of the IMF’s Advancing the Frontiers of Monetary Policy, who consider forward guidance to constitute best practice. Ksenia Yudaeva, the Bank of Russia’s First Deputy Governor, challenges their opinion, pointing to conditions in which forward guidance from a central bank might have an adverse effect, generating confusion instead of improving transparency.

We deem it imperative to understand forward guidance arrangements, and in order to enrich discussion of this matter, we draw attention to the opinions and comments on the effectiveness and risks of forward guidance provided by experts with hands-on experience: the leadership and researchers from those central banks that have ventured to disclose their key rate forecasts (the findings are published in the Russian Journal of Money and Finance).

Forecasts and commitments…

In 2009, Jan Qvigstad, Special Adviser at Norges Bank (then Deputy Governor), called the publication of projected paths for the central bank’s policy rate ‘the new frontier in central bank communication with the market’ and a priority area for future research. Ten years have passed since then, and several studies have appeared that help us better situate this practice among central banks’ tools. We have reviewed studies, working papers, and notes released by the central banks that practise forward guidance (the central banks of New Zealand, Sweden, Norway, and the Czech Republic) to evaluate the validity of concerns surrounding it.

In her review, Ksenia Yudaeva clearly and concisely summarizes the view of a central bank practitioner on issues connected to forward guidance, noting that the major risk is confusion between a forecast and commitment.

However, none of the studies we have reviewed provides real-world evidence that the perceived commitment problem has in fact ever materialized. Each of the central banks studied conveys the conditionality and the relative uncertainty of published forecasts in its own way, and all of their approaches have proven effective.

...and how to distinguish between them

The Czech National Bank (CNB), having adopted an inflation targeting regime in 1997, started publishing its key rate forecasts in 2008. At the same time, the bank began publishing a chart comparing its own historical policy rate forecasts with actual outcomes to draw attention to potential differences between the actual and predicted values.

In 2005, Norges Bank included in its first published interest rates forecast three alternative economic outlooks, showing different policy rate paths for each scenario. In so doing, it demonstrated how key rate decisions could vary according to the state of the economy.

Moreover, the central banks in question provide confidence intervals around the policy rate forecast to emphasize that the forecast is, in fact, a series of distributions and not a specific value. Confidence intervals reflect the uncertainty of the rate forecast, the result of both potential shocks and the mechanics of the economy.

Numbers vs. words

Confusion between conditional guidance and unconditional commitment can also occur when the central bank confines its communication to general comments on monetary policy. According to the literature we have reviewed, the predictability of policy declines when central banks rely on verbal statements alone, and increases when they provide specific figures along with these statements.

Norges Bank began analysing monetary policy expectations before it started publishing its rate forecast. In 1999–2005, the estimated average deviation of the rates expected by the market and the actual rates for a period longer than one year was more than 2.5 pp, which motivated NB to adopt a quantitative forward guidance strategy. Having analysed the Bank’s three years of experience in publishing interest rate projections, Amund Holmsen, former Deputy Governor of Norges Bank, and his co-authors found that the volatility of the 12-month money market interest rate almost halved the day after the central bank announced its decision. The public rate forecast has given market participants a clearer understanding of how the central bank reacts to the state of the economy.

Bank of Russia policy: market expectations and reality

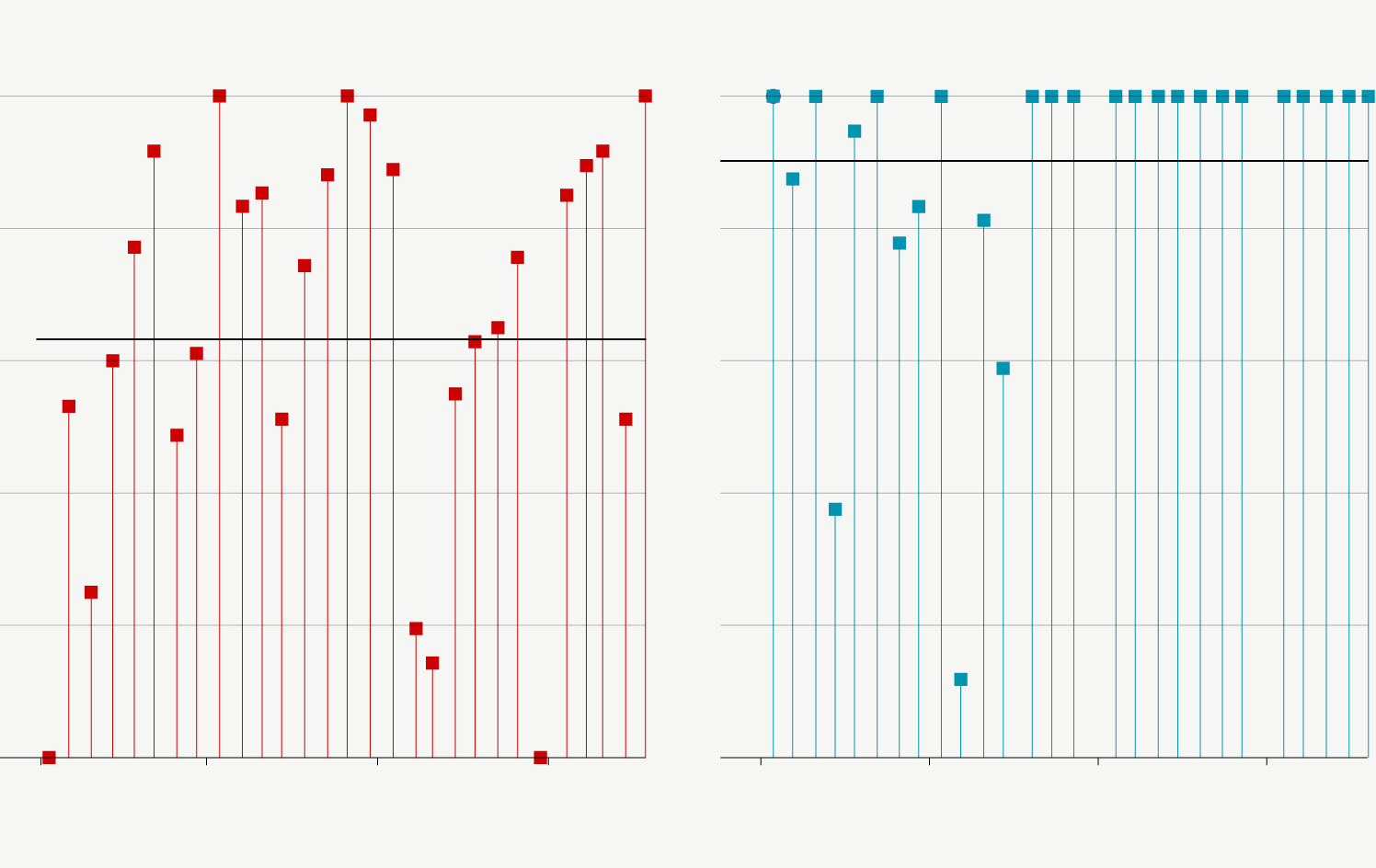

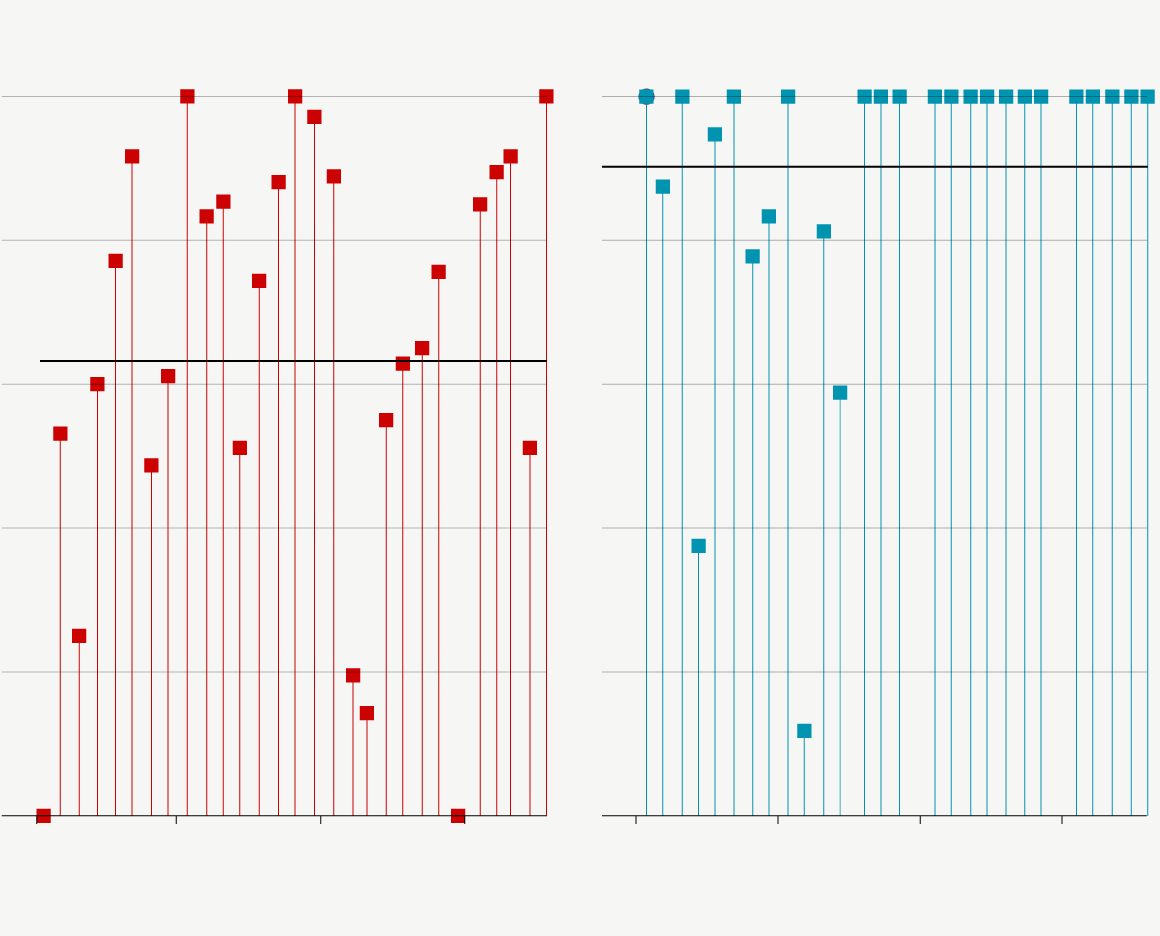

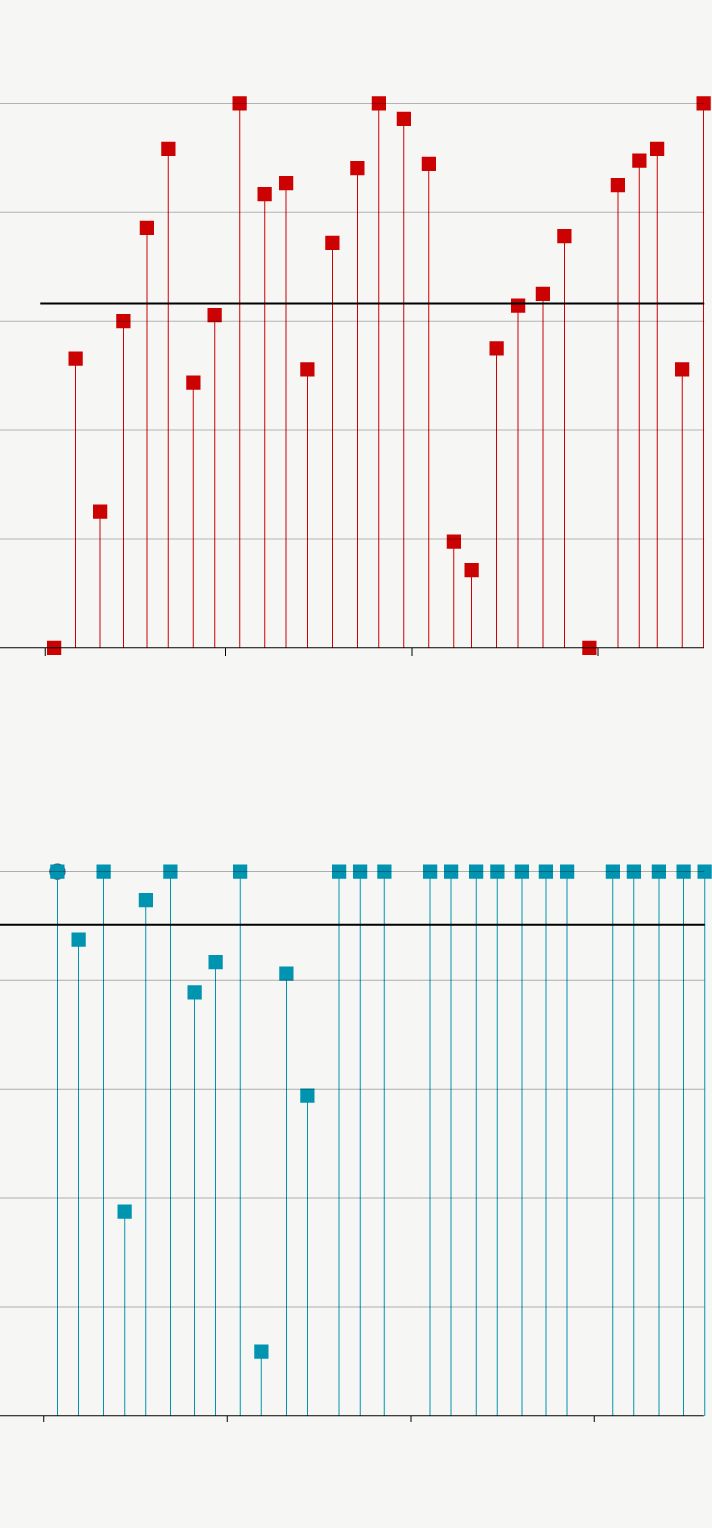

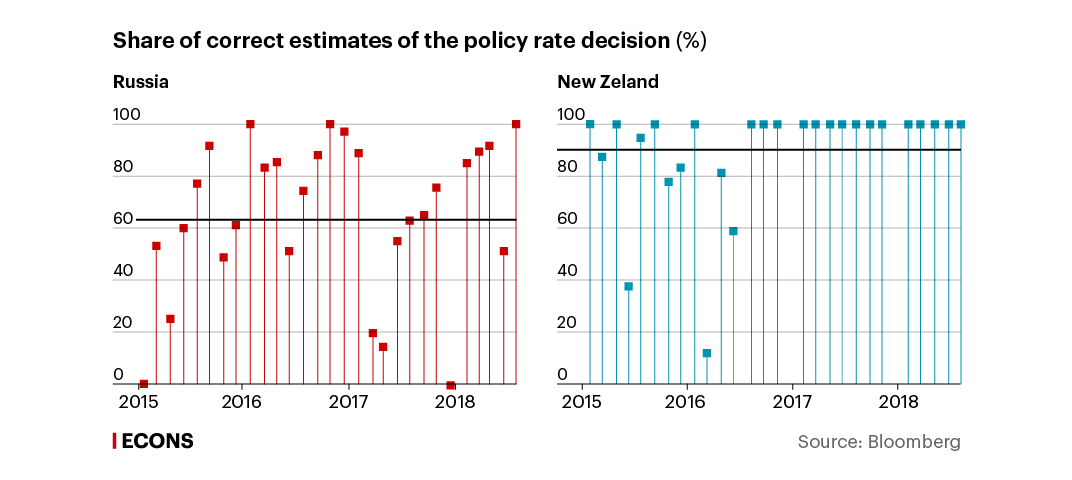

The long-term predictability of the bank’s policy is difficult to assess, especially when there is no forward guidance. However, it is possible to measure the short-term predictability of the Bank of Russia’s policy. To do this, we have studied the results of Bloomberg’s Analyst survey for the period from January 2015 to September 2018, when the floating exchange rate regime was in force, excluding Q4 2014, which is characterized by an initial shock after the adoption of the new regime. During this period, the Board of Directors’ estimates were correct in an average of 65% of cases. In five cases, fewer than 25% of the respondents gave the right forecast, and in two cases, the decision took all the forecasters by surprise.

Share of correct estimates of the policy rate decision (%)

Russia

New Zeland

100

100

80

80

60

60

40

40

20

20

0

0

2015

2016

2017

2018

2015

2016

2017

2018

Source: Bloomberg

Russia

New Zeland

100

100

80

80

60

60

40

40

20

20

0

0

2015

2016

2017

2018

2015

2016

2017

2018

Source: Bloomberg

Russia

100

80

60

40

20

0

2015

2016

2017

2018

New Zeland

100

80

60

40

20

0

2015

2016

2017

2018

Source: Bloomberg

Comparing the average rate of correctly predicted decisions in Russia in 2015–2018 with statistics from another country where the central bank has already adopted conventional forward guidance, we find that in New Zealand, for instance, where the central bank pioneered forward guidance, the rate is as high as 90%, compared to 65% in Russia.

Implications of forward guidance

The literature we have reviewed provides no justification for the major concerns expressed about forward guidance. On the contrary, having analysed the experience of four central banks that have been publishing their rate forecasts for the last 10–20 years, we have found that forward guidance may increase the predictability of monetary policy and the effectiveness of the transmission mechanism, and help markets better understand the policy implications of the new data, thus reducing interest rate volatility.

Certain papers suggest that the effectiveness of the guidance may decline if monetary authorities resort to excessive interest-rate smoothing, and emphasize that policy rate path publication is no substitute for verbal guidance, which is closely monitored by market participants.