In Russia, official poverty estimates are traditionally based on the cost of living. At the end of 2017, according to Rosstat, 19.3 million people, or 13.2% of the population, lived below the poverty line of 10,088 roubles. However, this approach has significant drawbacks. If we divide society into various groups based on median income, we see that far more people are badly off: 33% of Russians are poor or vulnerable to poverty.

Two approaches to income

All the existing approaches to income stratification can be split into two groups: absolute approaches, and relative approaches.

In an absolute approach, the boundaries of income groups are defined by a specific sum of money either in a national currency (calculated at the state level for the purposes of social and economic policy) or in dollars (for cross-country comparisons).

Relative approaches are more often used in developed countries, where there is no longer any need to consider the poverty line a question of actual survival, but rather a matter of sustaining a lifestyle typical for a particular society. It is usually based on the country’s median income (the median income is a level of income that divides the population into two equal groups, half having income above it, and half having income below it). This approach suggests that, in determining income groups, one should take into account the country’s overall income level and its distribution; it also allows for international comparisons. For example, the relative poverty line is usually defined as 0.5–0.6 of the median, as incomes below this level certainly do not enable people to maintain the standard of living that is typical for a particular society. However, it should be borne in mind that, although the relative value of this income is the same for all countries, absolute values may vary considerably.

The issue with the absolute approach

The poverty line in Russia is a special case of the absolute approach. It helps to determine who is most in need of social assistance, but does not allow the overall pattern of income distribution in society to be evaluated: for example, it does not reveal who is vulnerable to poverty and who might be considered middle class.

Multiples of the cost of living are sometimes used as income boundaries to divide the better-off into income groups, but whether these groups are homogeneous in terms of social status and behaviour is a controversial question. Moreover, the cost of living varies considerably from one region to another, while the calculation methodology itself is subject to occasional changes; it is therefore difficult to estimate the dynamics of income stratification correctly. Finally, the poverty line set by the state does not allow the Russian case to be compared with the situation in other countries.

Another example of the absolute approach is the World Bank’s methodology, which is widely used around the world. According to this methodology, people who live on less than $5 a day (in terms of purchasing power parity) are poor, people who live on $5 to $10 a day are vulnerable, and those who live on more than $10 a day are considered middle class.

Back in the early 2000s, Russians’ incomes were so low that this approach was effective. For example, at that point, 27% of Russians belonged to the middle class as defined by the World Bank. However, this methodology is no longer suitable for Russian society; it indicates that 90% of Russians could be considered middle class, while fewer than 1–2% are poor even during an economic slowdown (the calculations are based on microdata from nationally representative surveys by the Russian Longitudinal Monitoring Survey - HSE).

The problem here is that, from the very beginning, the World Bank’s income boundaries were created for developing countries, and in terms of income stratification models, modern Russia turns out to be much more similar to developed countries. In particular, extreme poverty as a matter of actual survival, which is still typical for other BRICS and Latin American countries, is almost non-existent in Russia.

Average standard of living

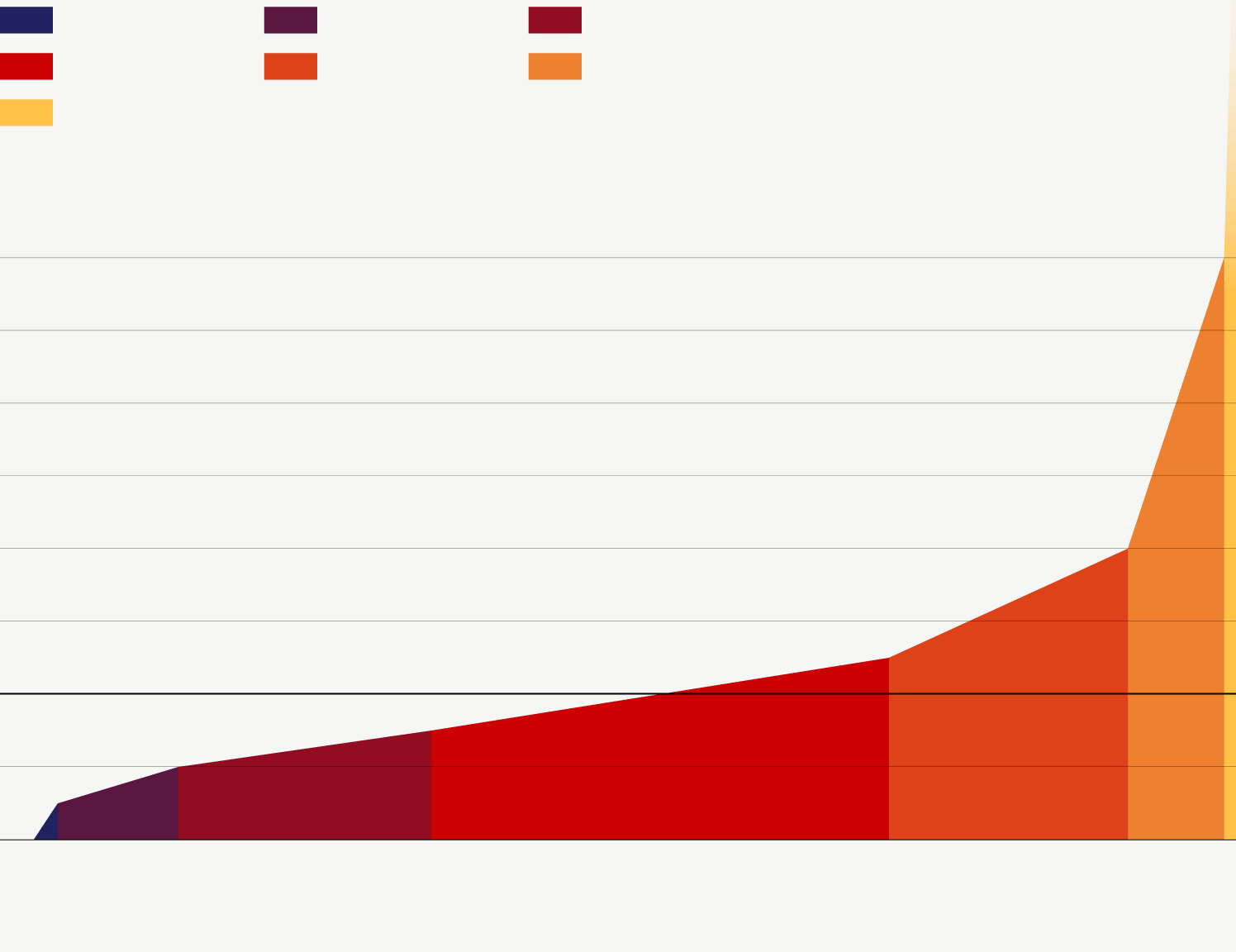

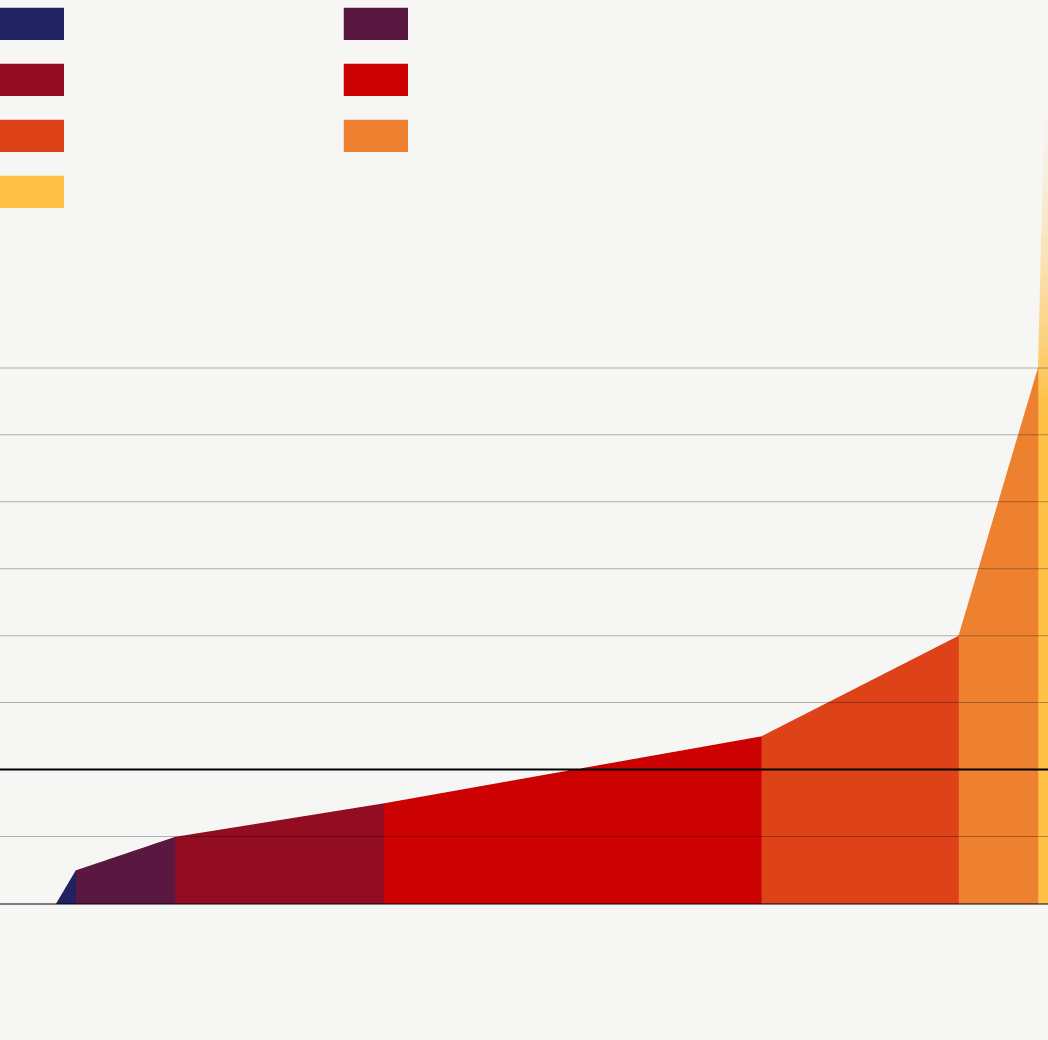

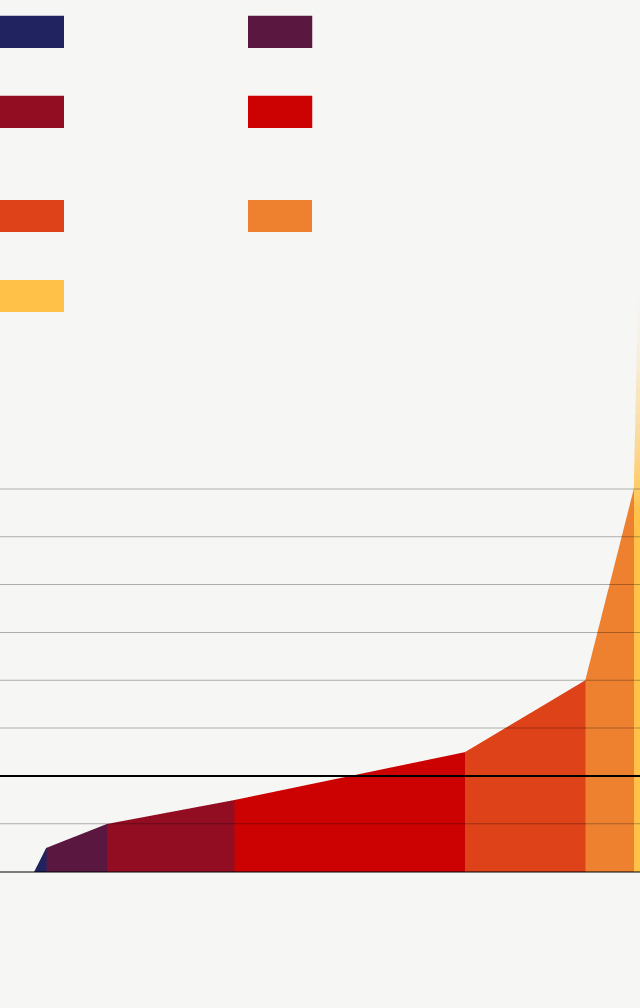

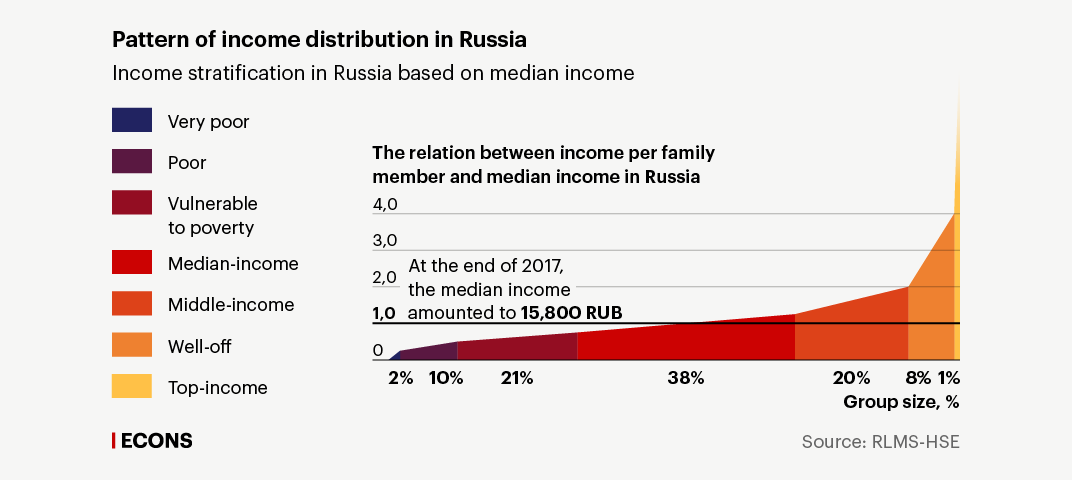

The relative approach based on median income produces more representative results when applied to Russia. Using this method, we have divided modern Russian society into seven income sub-groups, which can be arranged in three classes that are almost equal in terms of the number of people included: a well-off class, a disadvantaged class, and a middle class (see the chart ‘Pattern of income distribution in Russia’). We used data provided by RLMS-HSE suggesting that, at the end of 2017, the median income amounted to 15,800 RUB. This is much lower than Rosstat’s estimate of 23,561 RUB, as social income data gathered through surveys is usually different from statistical data.

Pattern of income distribution in Russia

Very poor

Poor

Vulnerable to poverty

Well-off

Median-income

Middle-income

Top-income

The relation between income per family member

and median income in Russia

4,0

3,5

3,0

2,5

2,0

1,5

1,0

At the end of 2017, the median income amounted to 15,800 RUB

0,5

0

2%

10%

21%

38%

20%

8%

1%

Group size, %

Source: RLMS-HSE

Very poor

Poor

Vulnerable to poverty

Median-income

Middle-income

Well-off

Top-income

The relation between income per family

member and median income in Russia

4,0

3,5

3,0

2,5

2,0

1,5

1,0

At the end of 2017, the median income

amounted to 15,800 RUB

0,5

0

2%

10%

21%

38%

20%

8%

1%

Group size, %

Source: RLMS-HSE

Very poor

Poor

Median-income

Vulnerable

to poverty

Middle-income

Well-off

Top-income

The relation between income per family

member and median income in Russia

4,0

3,5

3,0

2,5

2,0

1,5

1,0

At the end of 2017,

the median income amounted to 15,800 RUB

0,5

0

2%

10%

21%

38%

20%

8%

1%

Group size, %

Source: RLMS-HSE

The lower income group includes Russians with incomes below 0.75 of the median, disadvantaged members of society who amounted to one-third of the whole population in 2017. This group is mainly comprised of Russians who are vulnerable to poverty rather than poor, who are poised on the edge of poverty and are at risk of a drop in their standards of living should their personal circumstances or the general economic situation change. This group turns out to include far more people than just the officially poor, whose incomes are lower than the cost of living.

Today, the median group that includes people whose incomes are at least 0.75 of the median but less than 1.25 of the median is the largest, accounting for 38% of the population. It represents an average standard of living in Russia. By and large, this is a very modest standard: only a small share of this group find their financial circumstances satisfactory, and they have next to no opportunities to improve their consumption, while simultaneously having little in the way of a safety net (for example, significant savings). However, their standard of living is much higher than the standard needed for survival: for example, they have good supplies of durable goods, and more than half of them have cars. What’s more, the increase in consumption over the last 15 years has had the greatest impact on this very group.

Overall, the Russian median group is poised between well-being and poverty.

Finally, the middle-income group (with a range of incomes between 1.25 and 2 times the median) and higher-income groups (with incomes more than double the median income) together represent the better-off part of society, accounting for 20% and 9% of the population respectively. The richest 3–5% of Russians are not included in the samples, so the middle- and higher-income groups constitute the well-off proportion of the mass population.

These people’s living conditions are more stable, while their standard of living is relatively high. They can choose what to do with the money they have left after their basic needs are satisfied, and are able to build up financial safety nets. Members of this class have greater access to consumption opportunities which are limited for the general population (trips abroad, foreign cars, expensive durable goods, and so on). That said, middle-income and high-income Russians have quite different standards of living, and opportunities are distributed unevenly among them.

Changes in poverty and well-being

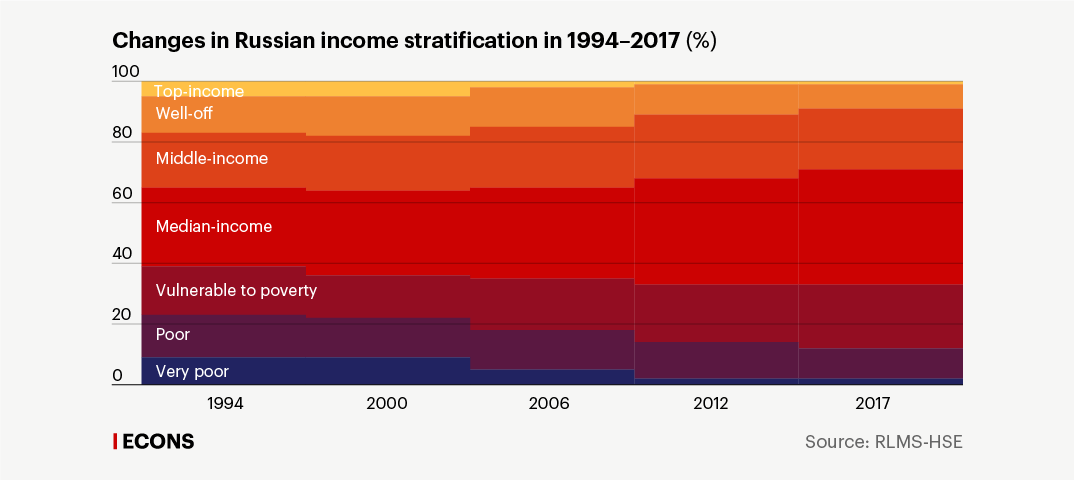

However, since the mid-1990s, this well-off class has shrunk from 35% of the population in 1994 to 29% in 2017 (see the chart ‘Changes in poverty and well-being’). At the same time, the share of people with a low income has also been shrinking. These two processes shaped the median class, which is currently the largest, increasing its share from 25% in 1994 to almost 40% of the population. In recent years, Russia has seen the rise of levelling tendencies in the income of the population at large, while the gap between the general population and people with the highest incomes has been growing even wider, according to data on income and wealth concentration in the top 1–5% of the population (see reports by Credit Suisse and the World Inequality Database).

Changes in Russian income stratification in 1994–2017 (%)

100

Top-income

Well-off

80

Middle-income

60

Median-income

40

Vulnerable to poverty

20

Poor

Very poor

0

1994

2000

2012

2017

2006

Source: RLMS-HSE

100

Top-income

Well-off

80

Middle-income

60

Median-income

40

Vulnerable to poverty

20

Poor

Very poor

0

1994

2012

2000

2017

2006

Source: RLMS-HSE

100

Top-income

Well-off

80

Middle-income

60

Median-income

40

Vulnerable to poverty

20

Poor

Very poor

0

1994

2012

2000

2006

2017

Source: RLMS-HSE

These levelling tendencies were expected to reduce social tensions in lower- and middle-income groups, as according to public opinion, inequality is one of the most pressing social issues. However, in fact, this problem is not becoming any less acute, and is still a tremendous brake on the country’s current development. Our previous studies have shown that “ordinary Russians” are mostly frustrated by the widening gap between themselves and the few ‘at the top’ rather than by the scale of inequality among other mass groups.

Besides, Russians are more concerned about the unfairness of the basis for modern Russian inequality than they are by income inequality itself (indeed, they tend to consider a certain level of inequality necessary). They do not want universal income levelling, but rather equal opportunities, so that different incomes are shaped by legitimate factors such as education, qualifications, efficiency, and so on. At the same time, the most educated and qualified Russians are not happy with the income-levelling tendency in mass groups and shrinkage of the higher-income group, as for them as for them this means reduction in chances for achieving higher quality of life.