The theory of gravity states that objects are attracted to each other in a manner that is directly proportionate to their mass and inversely proportionate to the distance between them. But gravity exists in economics as well as in physics. And just like in physics, its effect is objective. It has to be considered in economic policy.

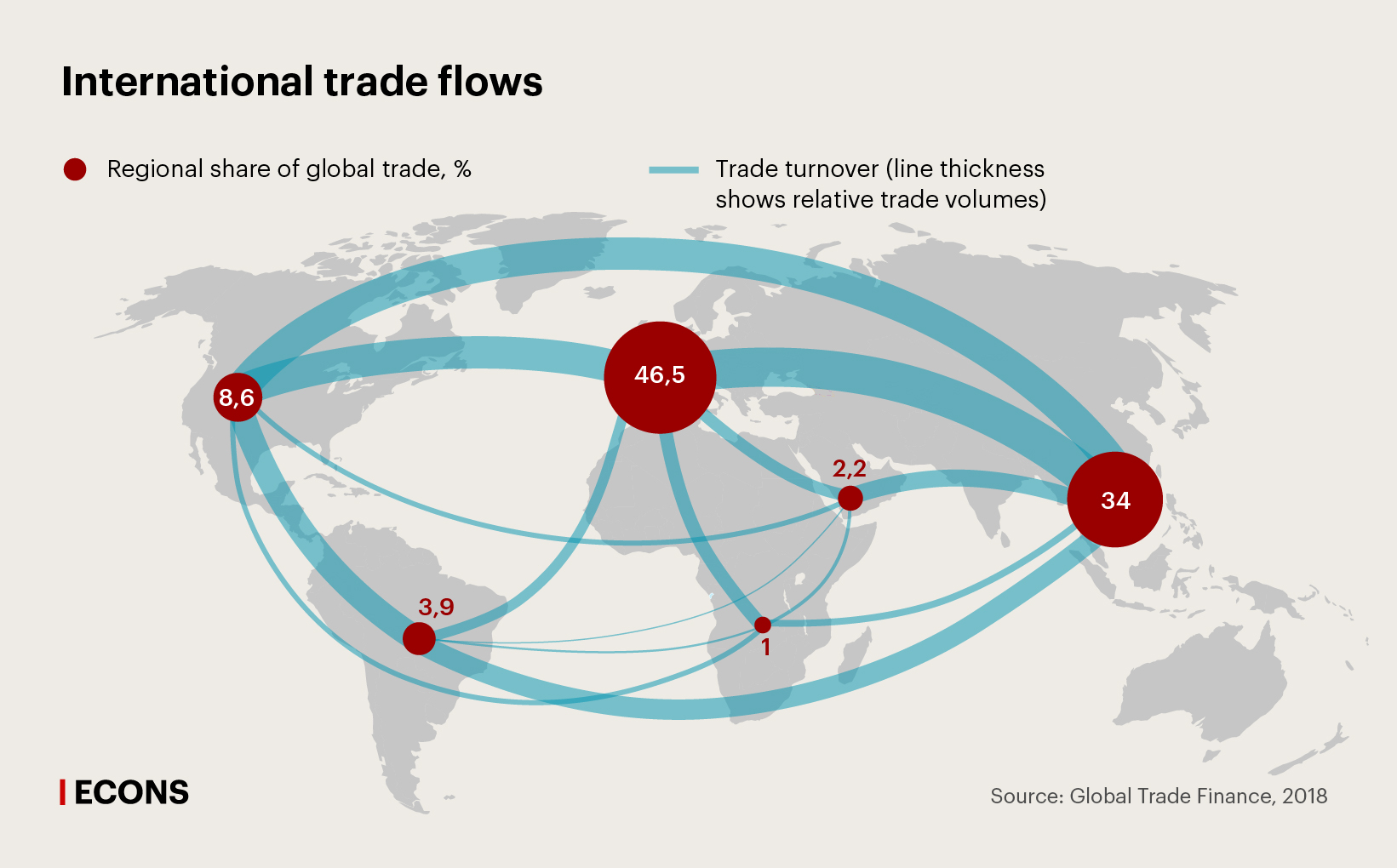

How does gravity work in economics? It can be interpreted like so: the economies of the two countries interact (trade) with each other in direct proportion to their size (i. e. GDP) and inversely proportionate to the distance between them. Providing all other factors are equal, the larger the national economy, the greater the turnover of foreign trade with all other countries. Trade with geographically adjacent countries is much more active than with distant countries that have economies of the same size.

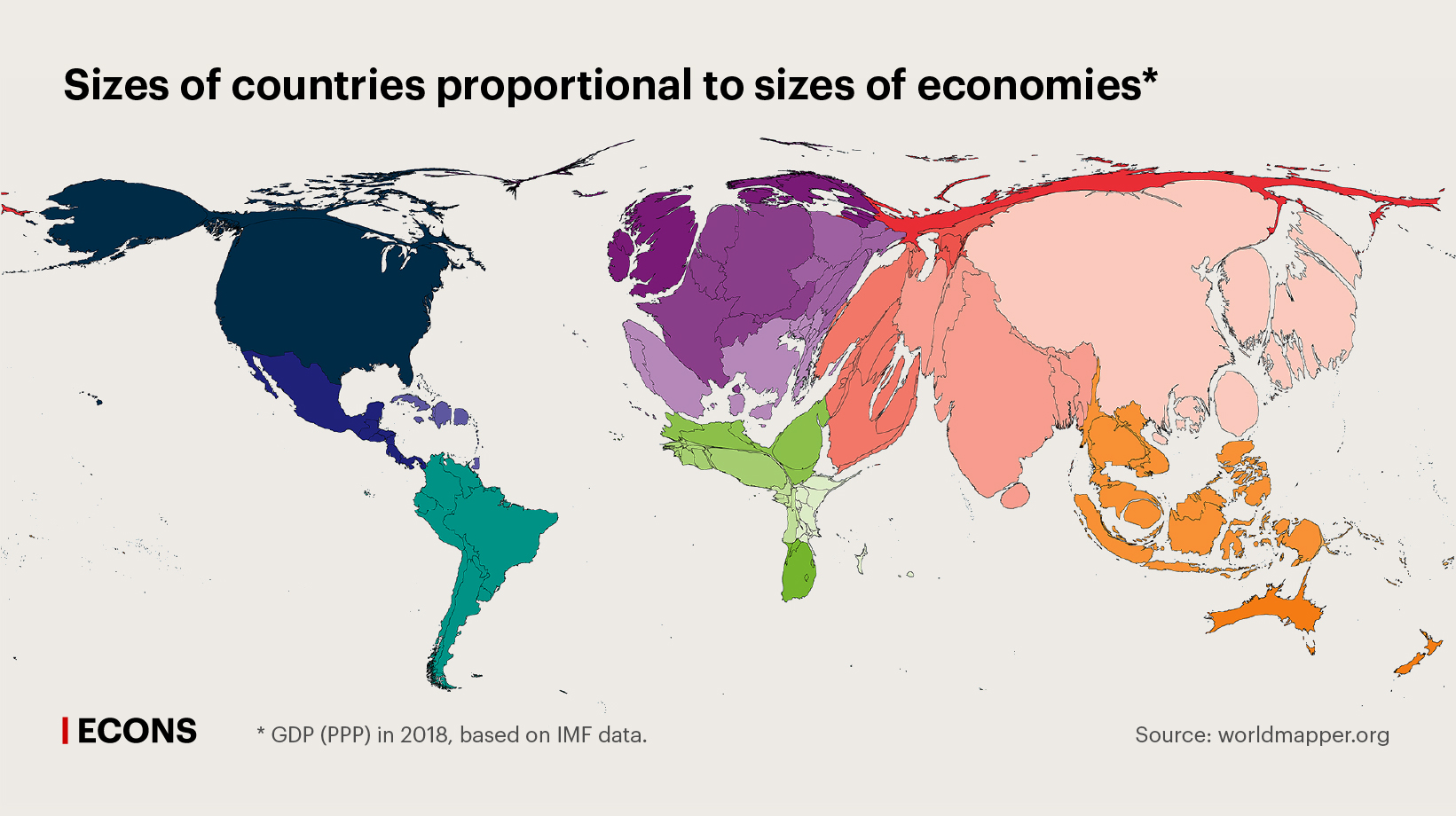

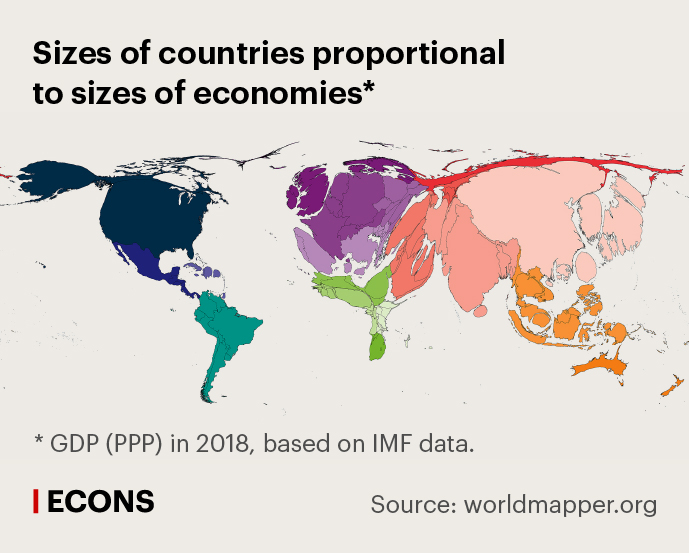

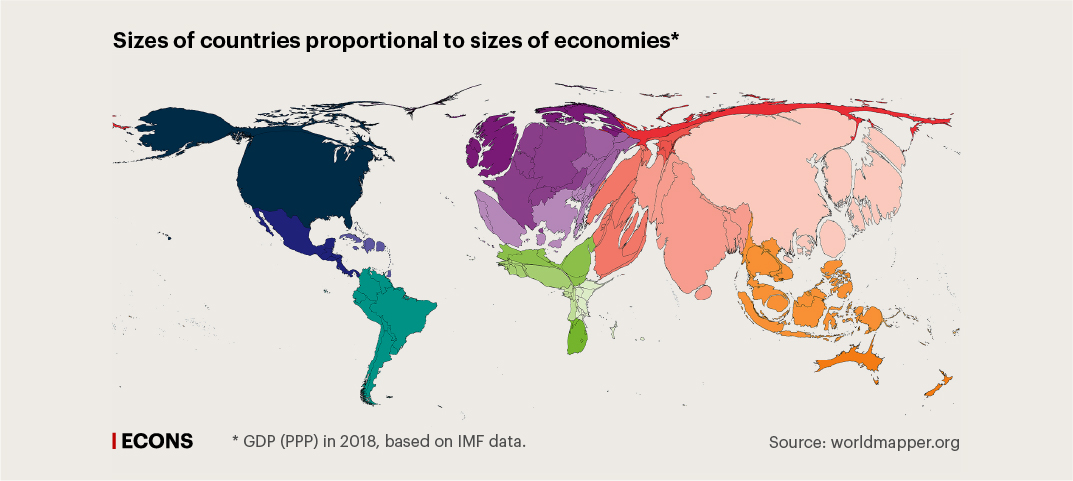

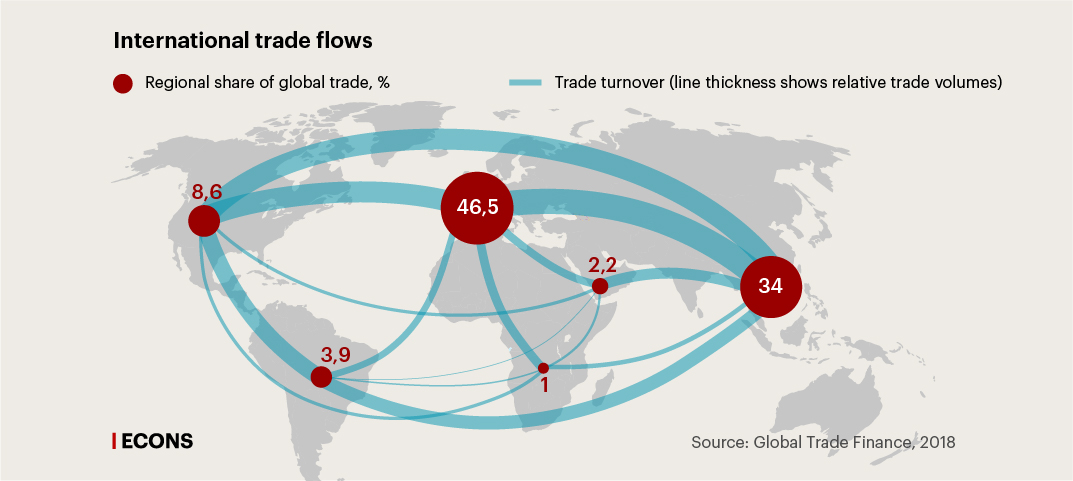

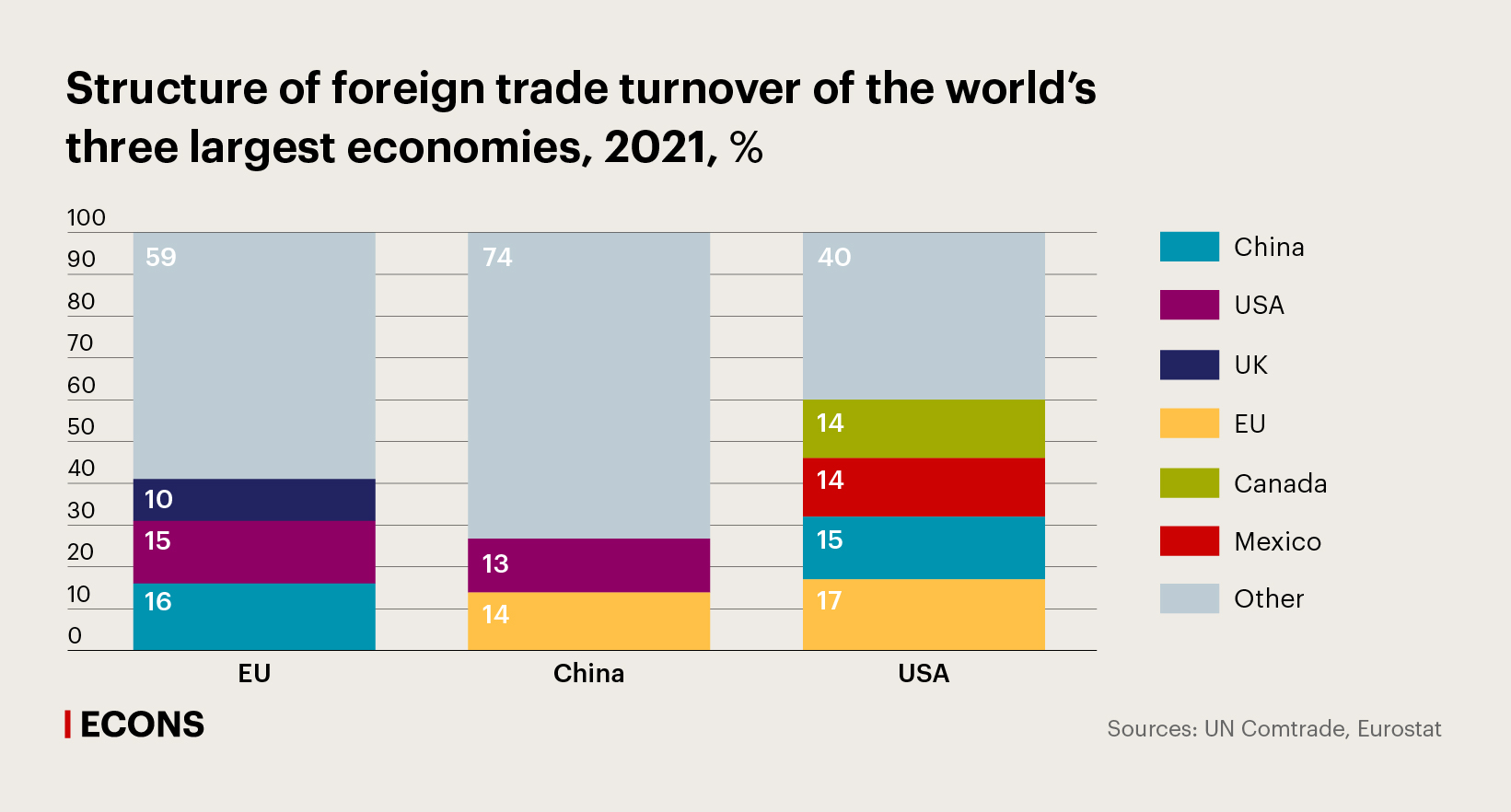

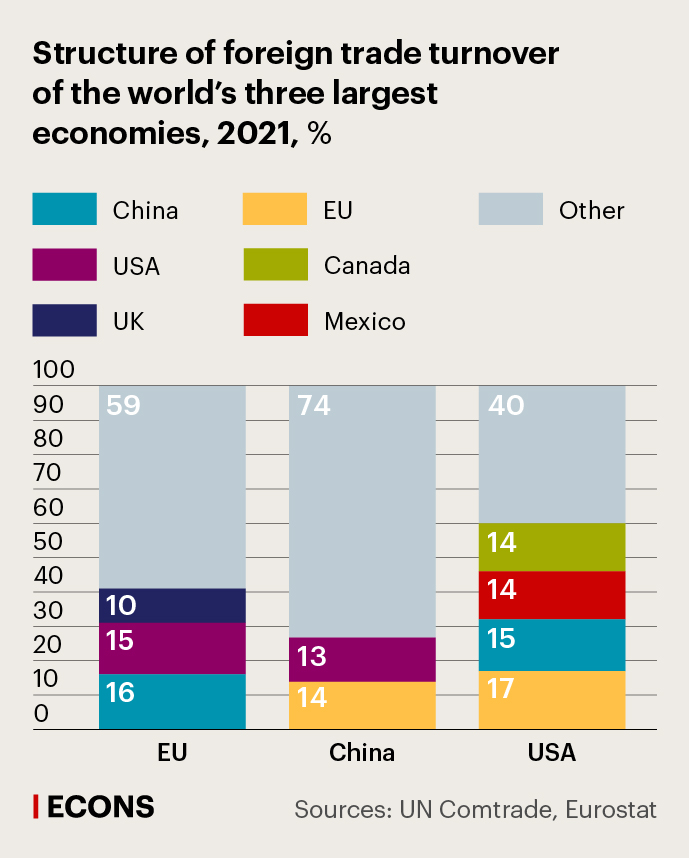

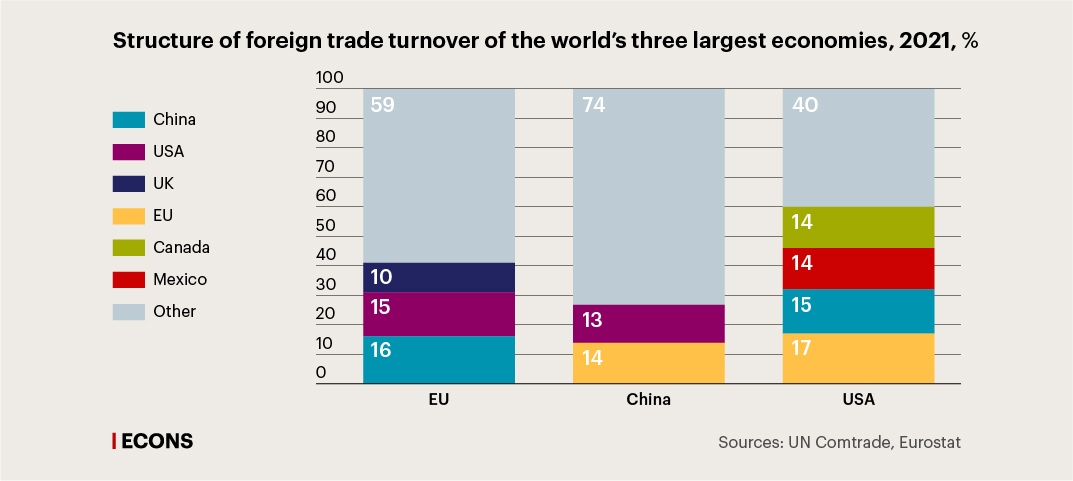

Thus, it is no wonder that the world's three largest economies – the United States, China and the European Union – trade the most among themselves, and for the rest of the world, one, two, or all three of these economies are generally among other countries’ biggest trading partners. Geographically, these three economies are relatively close to other countries. This determines both the economic power and ultimately the political clout of these countries (see charts below).

Why is this happening? First, the largest economies have huge markets. For companies exporting from other countries, this presents a fantastic opportunity to increase production and profits. A small economy alone does not provide such an opportunity. Second, if for small economies, the main trading partners are the largest economies, then for the largest economies, small and even large economies represent a relatively small share of their trade turnover.

The loss of markets in the largest economies as a result of disruptions in trade relations is a severe blow to both smaller economies as a whole, and individual companies. For the largest economies and their companies, the loss of local markets in smaller economies is a nuisance, but not a problem. This results in asymmetry. It is far more important for small countries to maintain and develop economic ties with the largest countries than for the largest with small ones.

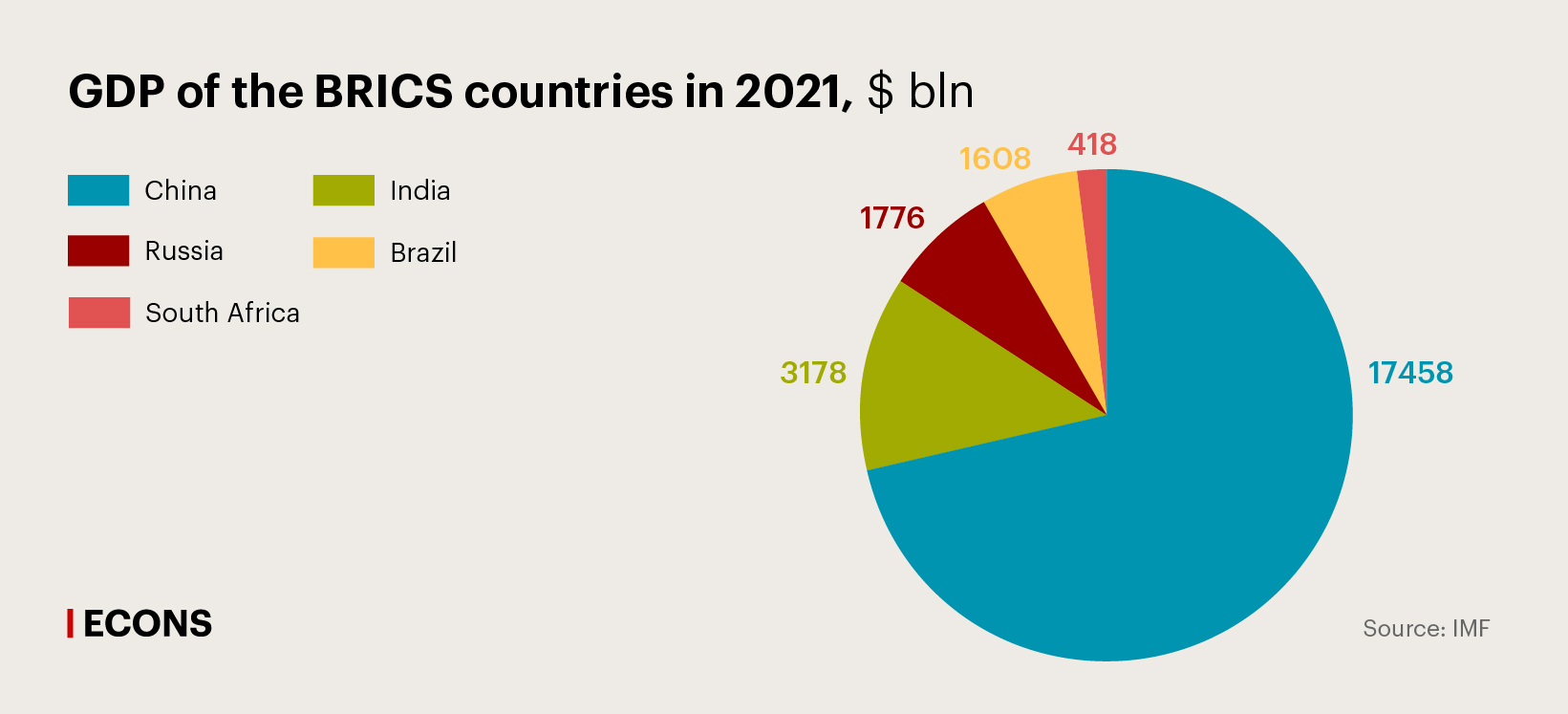

Among the BRICS countries, China clearly stands out in terms of economic size (see chart below). For other BRICS countries, trade with China is important (18 % of Russia’s trade is with China) or even decisive (27 % of Brazil’s trade is with China) due to the size of China’s economy. In other words, if it had not been for China, BRICS would have lost its importance as an economic association. Of course, given the demographic potential, India's rapidly growing economy could eventually catch up to China. But this is a long-term process (United Nations projections show that India will overtake China in terms of population in 2023, while the size of its economy in the foreseeable years will remain about five times smaller, according to IMF calculations).

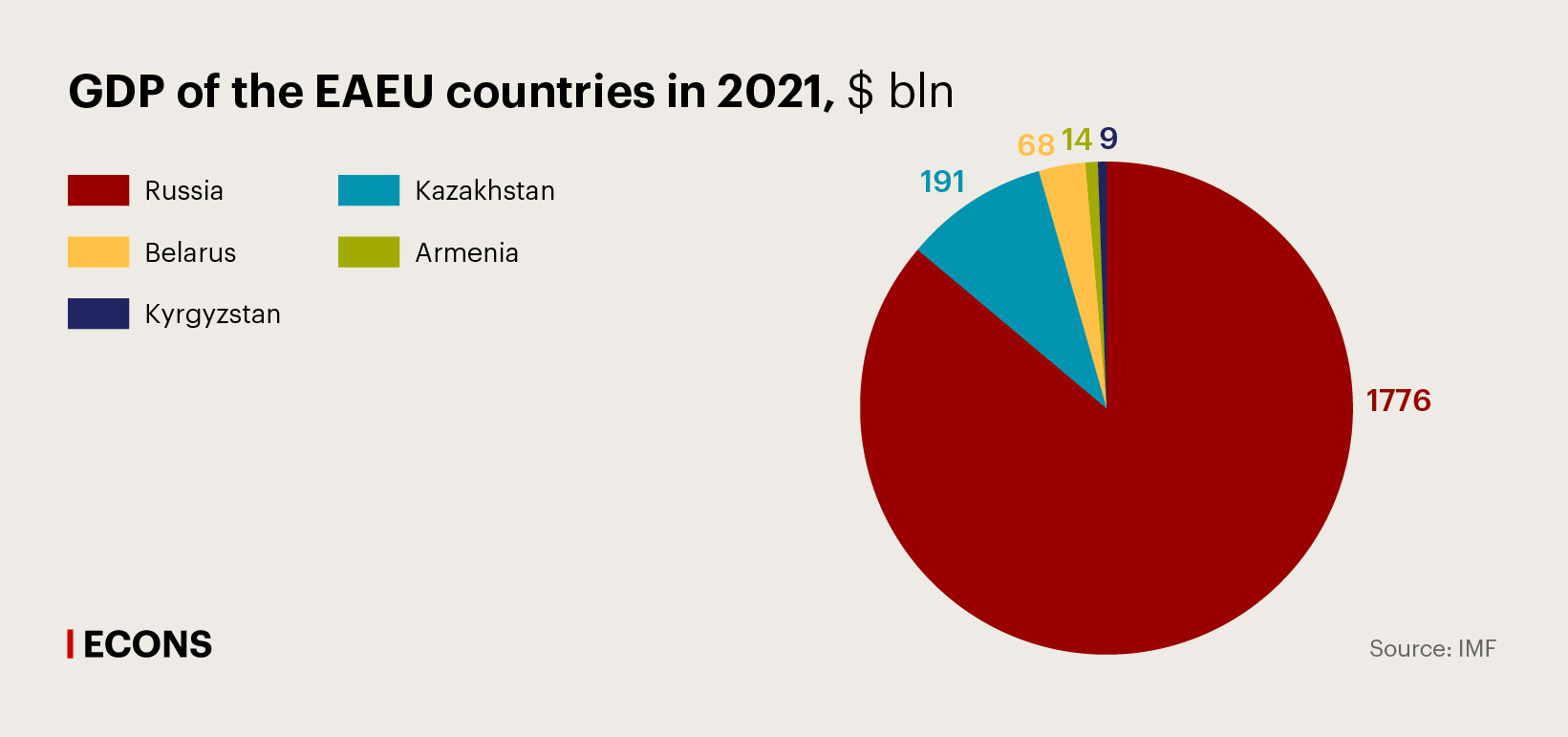

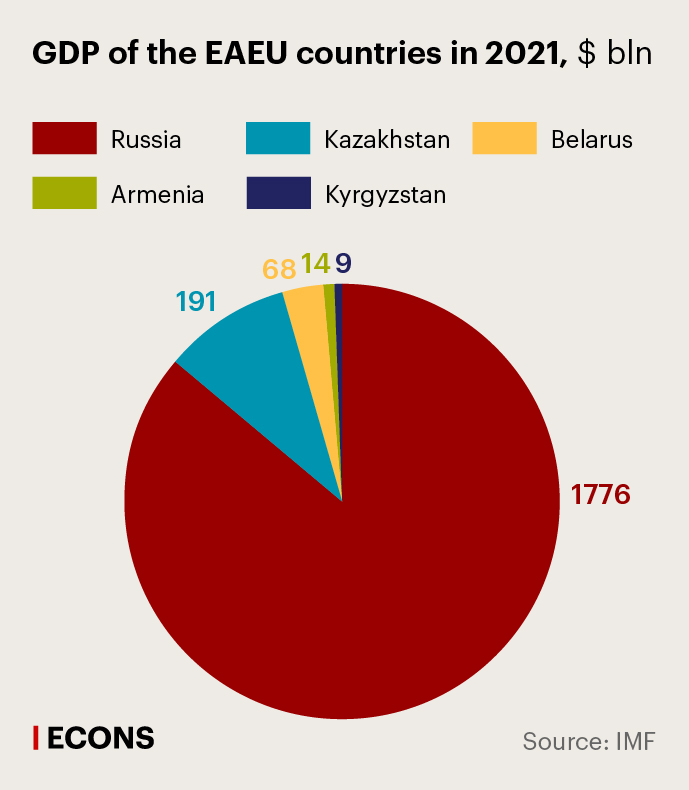

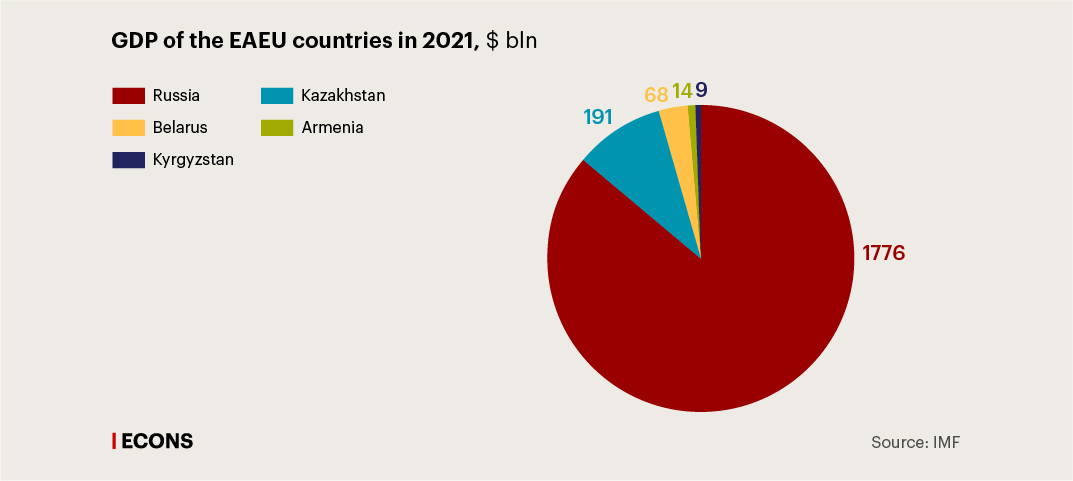

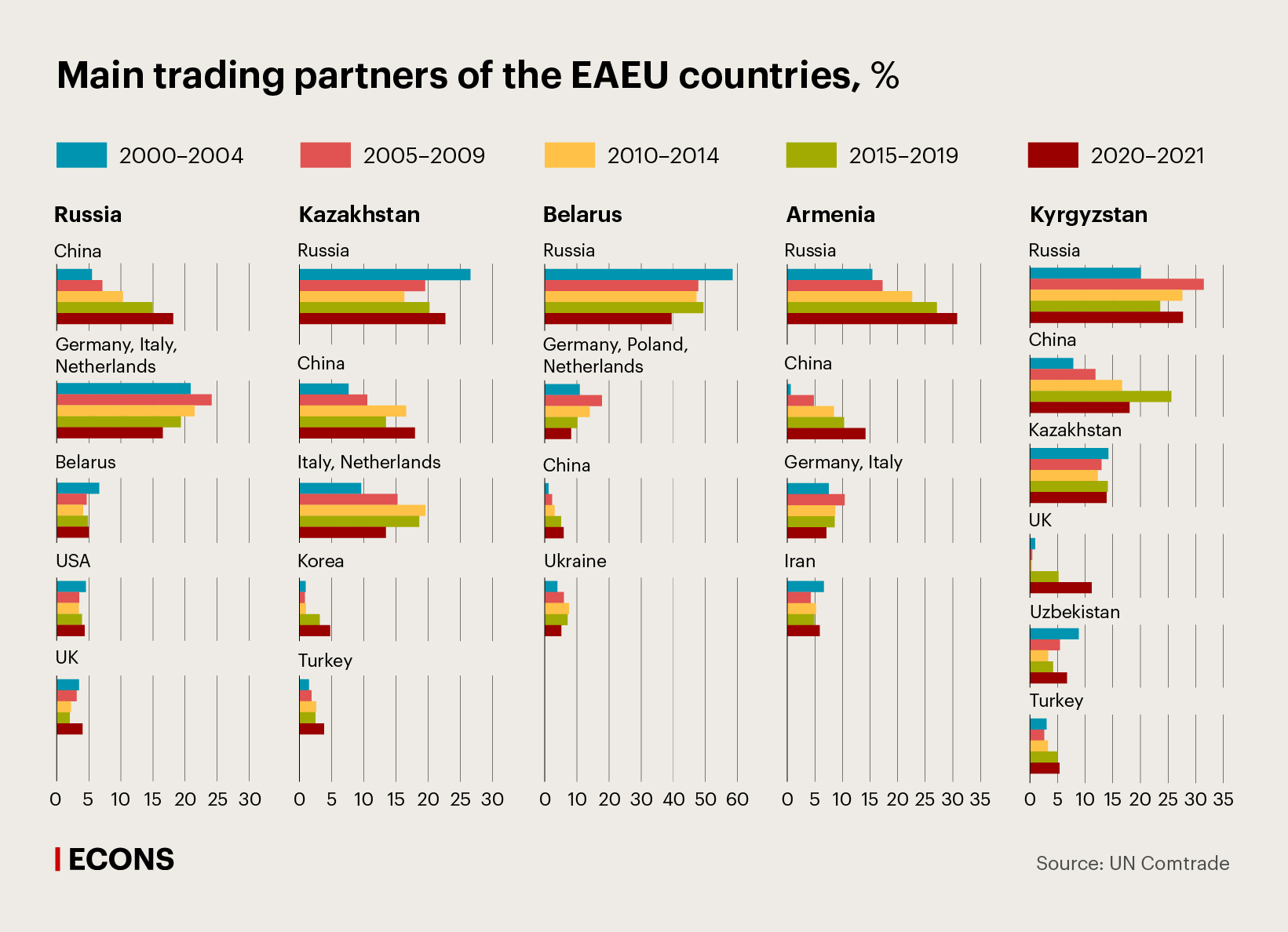

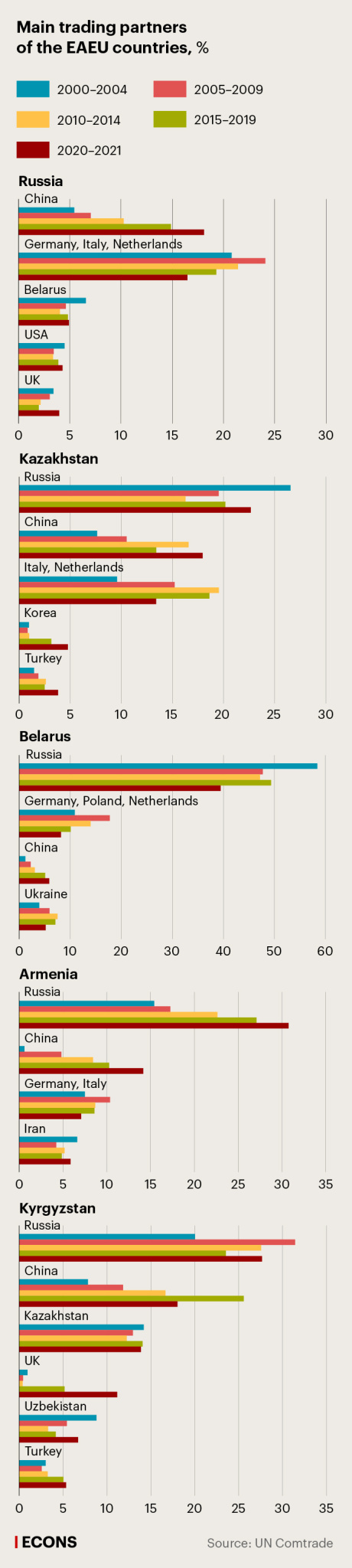

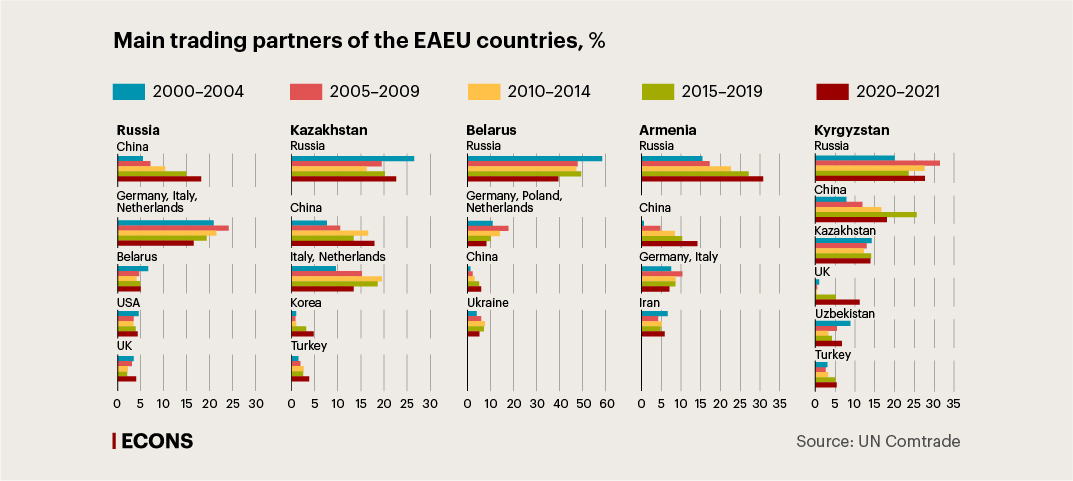

If we look at the Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU), we can see that the Russian economy plays a dominant role by attracting neighbouring economies (see charts below). However, two of the largest economies, the European Union and China, are located next to Russia, meaning that gradually, albeit non-linearly, the gravitational field of the Russian economy has been overpowered, thus defining the main trajectory of foreign trade of other EAEU economies.

Of course, not everything depends on size and distance, but both of these factors are important. In terms of distances, the nature of trade presupposes, among other things, not only the existence of national borders, but also infrastructure, sea routes where the world's major freight traffic takes place, the complementarity of economic and foreign trade structures (including the uniqueness of goods being supplied), political, historical, migratory and cultural ties between countries, and common or similar languages. However, these traits represent adaptations to the general rule that follows from the gravity theory. It is possible to overcome gravity, but this requires a lot of effort, while one can stay within the gravitational field with minimal effort.

So, what does this mean? Gravity theory suggests that maintaining and developing foreign trade ties with the European Union and the United States, ceteris paribus, should be a priority for China (see chart below). Developing trade with Russia is important, but the Russian market is not as large as the European and American markets. In this regard, Russia may be more interested in China than China is in Russia. Other countries in East Asia and the Pacific region are strongly attracted to China, both economically and geographically. Russia can hardly expect to take a leading place in their foreign trade.

In fact, due to the sanctions, Russia has no option in terms of trade gravity other than to further expand its economic ties with China, such as by building new transport corridors and establishing foreign trade logistics, thereby reducing the distance, as it were, between the two economies. The development of Russian trade with regional Asian powers such as Turkey, India, Iran, Indonesia, and Vietnam will be inferior compared to going the “Chinese route” in terms of its macroeconomic impact. The EAEU and Central Asian countries are also becoming increasingly integrated into China's foreign trade and production chains, increasing China's economic influence over the region as a whole.

In the current geopolitical situation, Russia as a whole is more interested in reorienting towards China and Asia than the countries in the region. For Russian companies such a rapid shift may require concessions in foreign trade negotiations. These may include offering significant price discounts on exported Russian goods compared to world market prices (benchmarks).

It is important to understand that expanding trade with China can be an opportunity for Russia not only to diversify its energy exports, but also to diversify its economy. This requires a set of policies aimed at easing pressure on business, increasing labour productivity and attracting direct foreign investment from China.

In the long run, we can only get out of the gravity of the largest economies by creating our own gravity to become one of the largest economies in the world. This is possible if the Russian economy significantly outperforms other economies, especially the largest, in terms of growth rates over at least a decade.

This was the case at the beginning of the 21st century. The Russian economy grew at an annual rate of about 7% based on fast-growing private companies. Can that be done again? If we want to achieve this, we need the same “animal spirits” and entrepreneurial confidence we had 20 years ago. This requires entrepreneurs, the dominance of private companies in the economy, confidence in the future and an understanding of future demand, a level playing field, significant decriminalization of commercial criminal law, effective protection of property rights, and a radical reduction in regulatory and administrative barriers.

In addition to geopolitical de-escalation and domestic institutional factors, the limited size of the domestic market (link in Russian), which makes it impossible to gain significant benefits from minimizing fixed costs, must be overcome if we want to even discuss the possibility of an economic miracle. For that, we need to build up our business from an export perspective. This makes it possible to widen our domestic market.