The sanctions imposed since 2022 have been a large-scale shock for the Russian economy, with foreign trade having emerged as the key channel of their influence. Discussions on sanctions often tend to be reduced to their impact on Russian commodity exports. It is however not limited to such direct effects as supply constraints, complicated logistics and higher transaction costs of exports. The disruptions in established import chains proved to be no less significant channel of sanctions pressure on both domestic production and non-commodity exports.

The unavailability or sharp rise in the cost of supplies of imported components and equipment resulted in serious problems in a number of manufacturing industries, and some of them failed to adapt quickly to the new conditions. A prominent but not the only example of a strongly affected industry is the automotive sector.

Our estimates are based on Rosstat data on import use in production and Russian trade statistics reconstructed from trading partners’ data for 2019 Q1–2024 Q3. They show that the drop in intermediate imports at the onset of sanctions confrontation transformed into a more than twofold drop in manufacturing output (in absolute values).

The import shock had diverse effects on non-commodity exports in terms of the technological process: the exports of machinery and equipment, i.e. the most technologically advanced goods, were the most affected. This aligns with a global trend: imported components are used in production of exports more intensively than in production of goods for the domestic market. High-tech production and exports depend most heavily on imports because unique components are more difficult to replace, and adapting production chains to those replacements demands significant resources.

Mechanism of impact

The way import shocks spread across production chains and the implications for output are clear enough. Researchers have found that the extent of this influence not only depends on the intensity of use of imported components, but also on whether they can be substituted. According to an overview of empirical works, disruptions in the supply of intermediate goods, such as natural disasters, have significant economic implications for related companies, even when they have not been directly affected.

For instance, one study uses the example of the 2011 earthquake in Japan to demonstrate how the import shock propagates through corporate chains, undermining output and exports of their overseas subsidiaries. The output of Japanese companies’ US subsidiaries declined almost as much as imports from Japan. The research also shows that complex and specialised goods are harder to replace in the short term, as this requires adjustments of production chains. In some cases, substitution was virtually impossible in the short term.

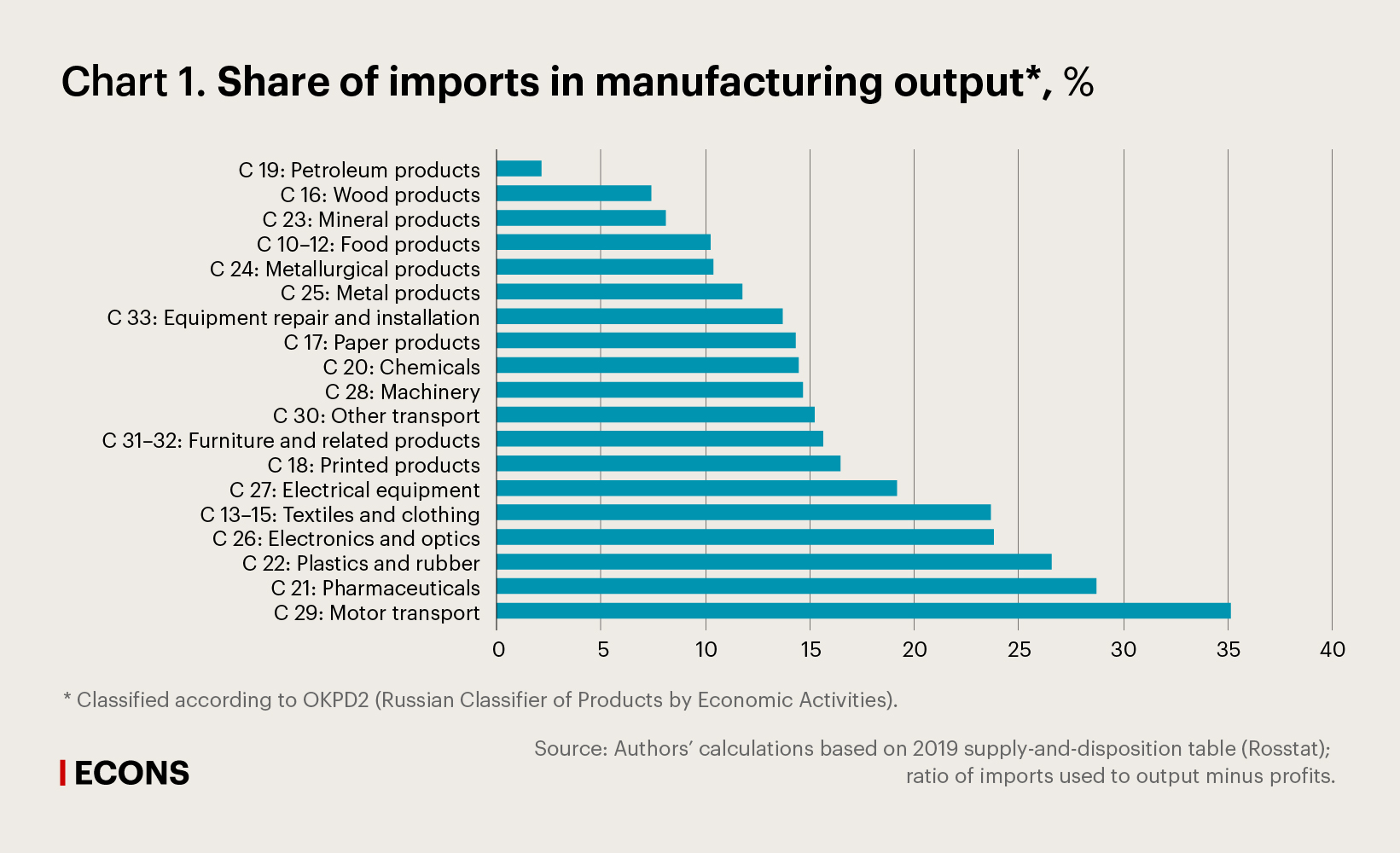

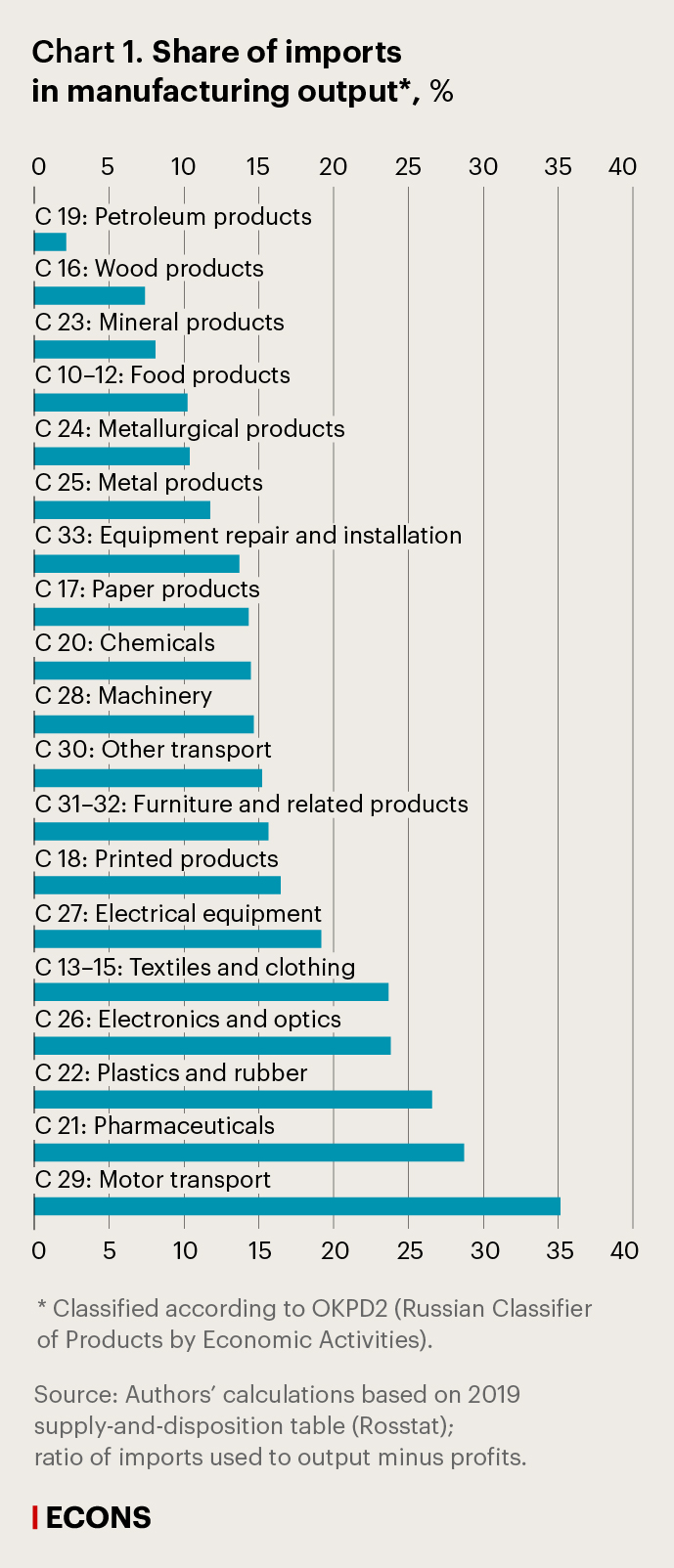

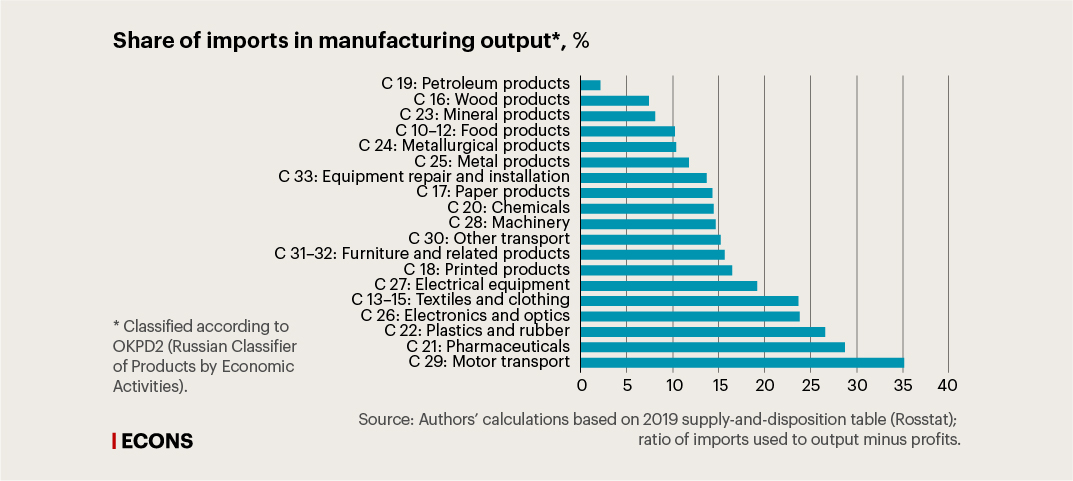

Russia’s manufacturing industry is marked by the highly variable use of imports. The scale and depth of the shock are clearly linked to how intensely imports are used in production.

Rosstat’s data for 2019 – the last ‘normal’ year – reveal considerable sectoral differences (see Chart 1). The ratio of imports (raw materials and other intermediary products) to production costs varied from 2.1% in the production of petroleum products to 35% in the automotive industry, which showed a record output decline among manufacturing industries in 2022.

In the period under review (2019–2024), two episodes of import decline and recovery were of non-economic nature: the Covid pandemic and sanctions. They can be therefore analysed as exogenous (external) import shocks of macroeconomic scale. Unlike in the pandemic, there were no administrative restrictions on domestic production at the time sanctions were imposed. This is why this situation can be viewed as a natural experiment and the impact of import restrictions on output can be assessed at sectoral level.

A similar situation was observed in 2020 Q1, when the pandemic was only affecting China and the intermediate goods it supplied. In his recent research (link in Russian) Dmitry Kuznetsov of RANEPA empirically shows that the drop in imports from China at the time had negative implications for production and exports in Russia’s manufacturing sector.

Impact on output and exports

Based on statistics available from Russia’s trading partners (over 80% of the country’s foreign trade turnover), we have reconstructed data on intermediate imports to Russia by commodity sectors. We then used Rosstat’s data on the shares of intermediate imports in total production costs (output net of profit) in the baseline 2019 year to calculate changes in these shares in 2019–2024 for each sector and quantify the impact on industrial output.

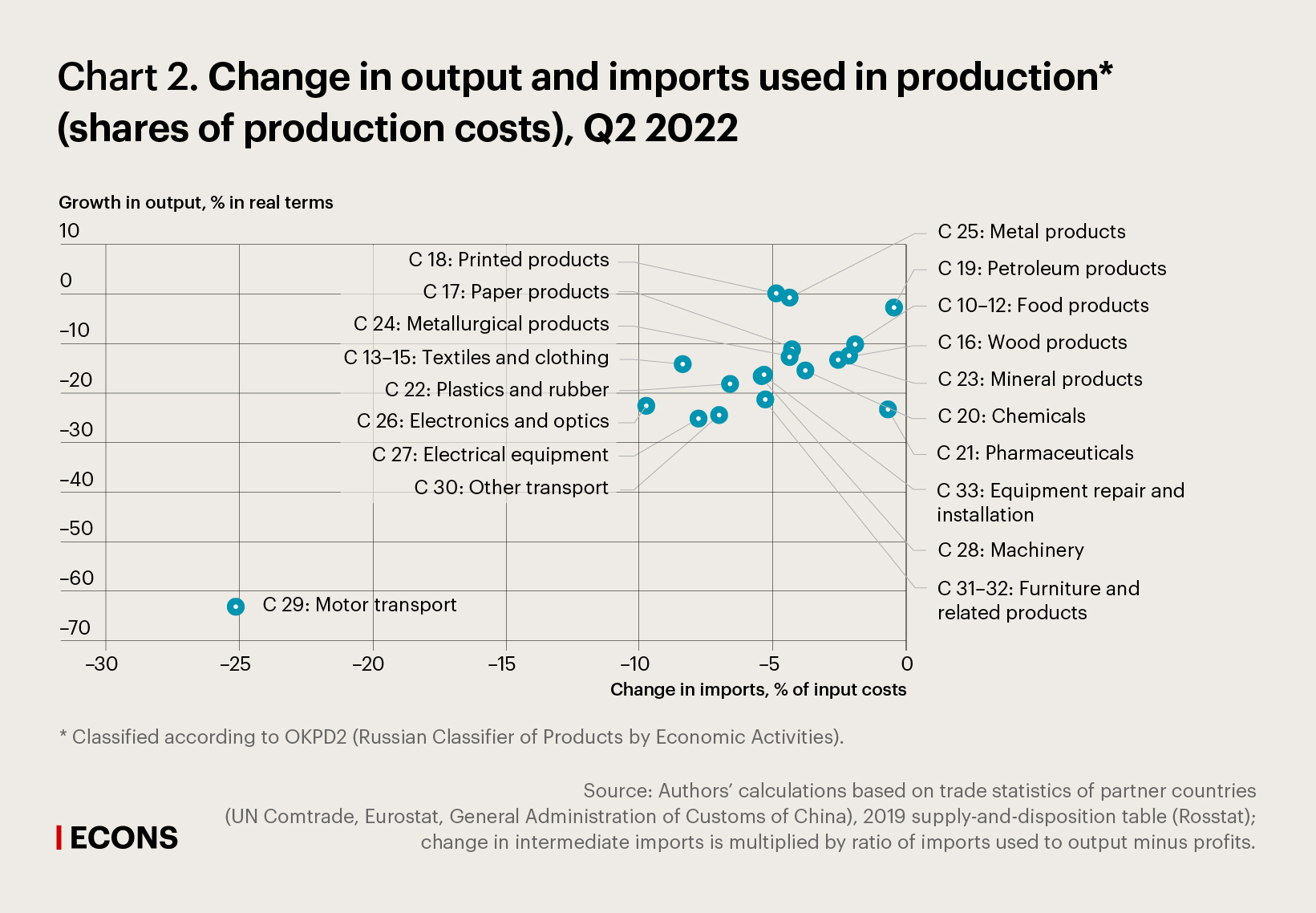

By 2022 Q2, some industries with a fairly high share of intermediate imports already showed a decline of 5–10% (in absolute terms) of input costs (see Chart 2). These industries saw their output drop by at least 14%. Chart 2 also shows that the automotive industry is an extreme case (this is why we exclude it from the sample and therefore avoid heavy distorted coefficients).

The empirical estimates confirm that the contraction of imports had a major impact on output. On average, in 2020 Q1–2024 Q3, a 1pp decrease in intermediate imports in manufacturing production costs led to a 0.88% reduction in output in the same quarter, that is, the drop in output in its value was almost equal to the reduction in intermediate imports.

However, the dependency ratio for the whole period under study also takes into account cases of changes in imports caused by production dynamics, for example when falling demand pushed down production. Estimates for the onset of the sanctions pressure more accurately reflect the response to the import shock – at the time, this relationship was significantly stronger.

In 2022, a 1pp reduction in intermediate imports in terms of production costs led to a 1.14% decline in output in the current quarter and a 1.33% decline in the next, meaning that the exogenous reduction in imports translated into a more than twofold decline in output (almost 2.5% over two quarters).

Over a one-year period, the impact of import contraction remains more than proportional to its contribution to production costs: each 1pp reduction in imports comes with a 2–3.1% decline in output. The negative effect stops growing by the end of the first or early second year after the import shock.

The impact of the import shock on non-commodity exports is diverse in terms of the technological process, with a more pronounced effect on high-tech goods. On average across all industries, a 1pp reduction in intermediate imports relative to total industry costs reduced non-commodity exports by 1.3% in the same quarter, and another 1.2% in the next. Notably, the exports of machinery and equipment, the most high-tech goods, reacted much more severely as they declined by 16% (11.6% and 4% in the same and next quarters respectively).

The stronger export response canот be explained by the more intense use of imported components, resulting in the share of imports in their costs being higher than the industry average. Moreover, high-tech production is more tightly integrated into global value chains, including through assembly lines, in which delayed supplies of components are more likely to cause a complete halt in production.

The same effect for average processed goods was 8.4% in the first two quarters (4.1% and 4.3% in the same and the next quarter respectively). For low processed products, which include homogeneous goods such as exchange-traded and non-energy commodities (e.g. grain, sawn lumber, steel), the results were unstable and more dependent on prices that were rather volatile over the period under study.

Thus, the import shock had the greatest impact on high-tech industries, deeply integrated into global value-added chains and therefore highly reliant on supplies.

Refocus of imports

Although the stop of supplies of components and equipment, primarily from advanced economies, had an adverse impact on output and exports of Russian manufacturing sectors, we observe a significant increase in supplies from neutral countries, evidenced by mirror trade statistics of partner countries. We find no major differences in the responses of production and exports subject to the group of countries from which intermediate goods originate. Among possible explanations are the successful switch to components from neutral countries and the nominal nature of this refocus.

An interesting question in this regard is the extent of the switch to components from alternative sources – this takes time and adjustment of production – and the extent of workarounds for supplies of the same goods from hostile countries. The bypass supplies are difficult to identify, but their scale is clear even from foreign trade statistics of partner countries and particularly noticeable in small economies.

Thus, Armenia recorded an increase in imports of various types of equipment from third countries almost of the same order as the rise in exports of the same goods to Russia. For example, imports of communication and imaging equipment to Armenia increased by $628 million (7 times), and the value of Armenian supplies to Russia increased from virtually nothing to $500 million. A similar dynamic is seen in monitors, projectors, computers, and household appliances. Consequently, it can be argued that the decline in imports into Russia of goods produced in hostile countries was somewhat smaller than their trade statistics suggest, due to supplies through neutral countries.

Nevertheless, even in cases where supplies were uninterrupted, the disruptions in logistics and complications in cross-border payments sent procurement, and by extension, production costs higher. These factors were likely partially offset in 2022 by a strengthened ruble in the case of domestically focused production, but not exports.