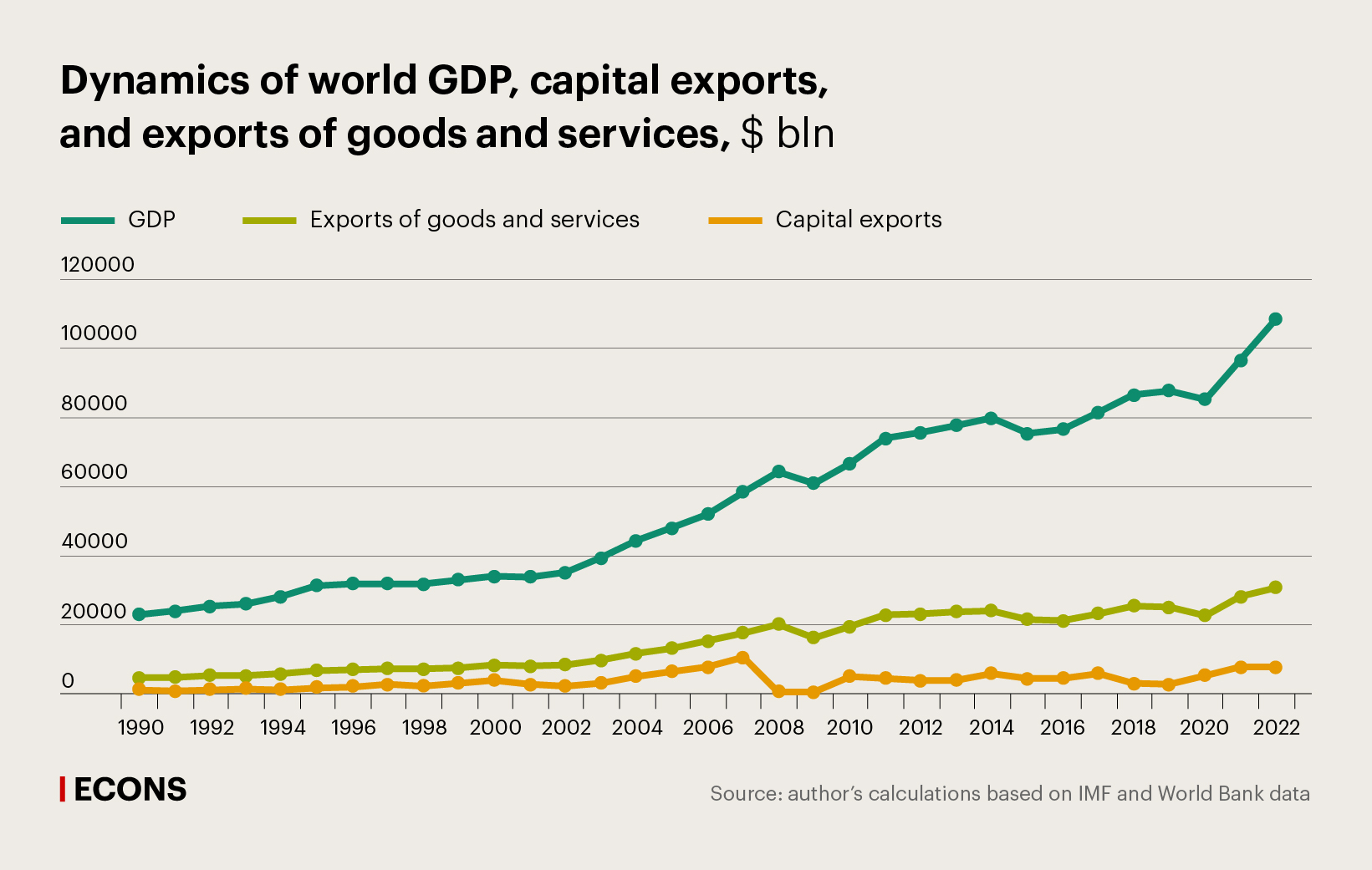

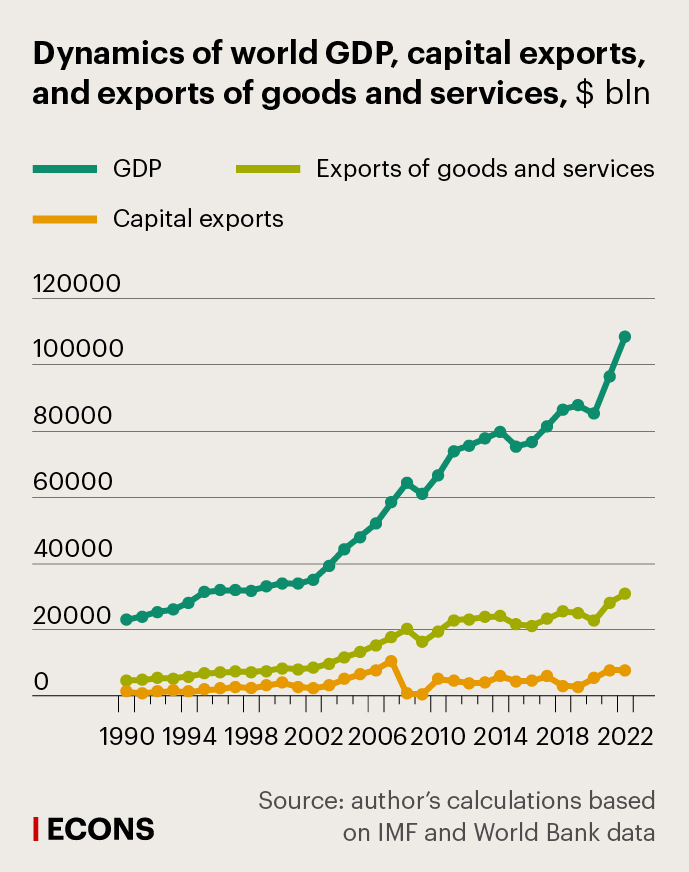

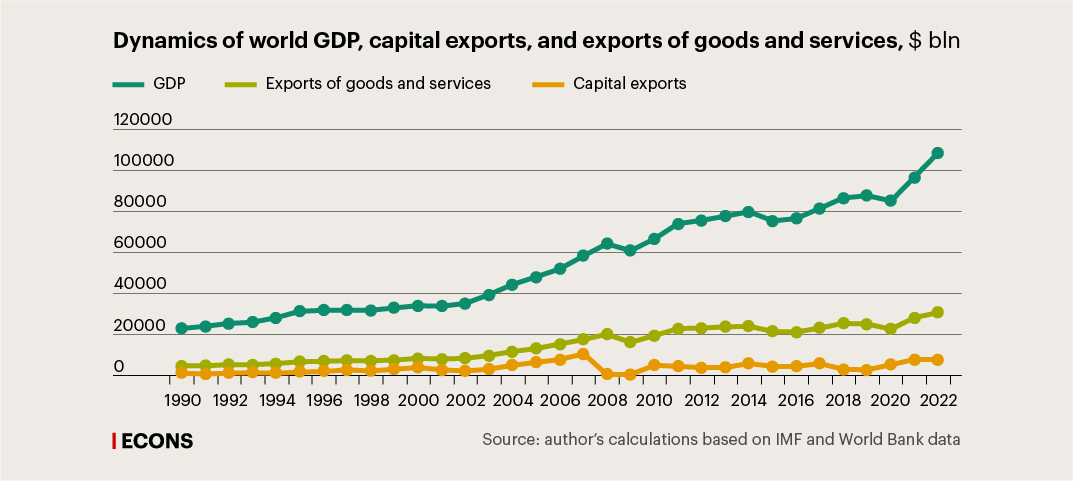

The new reality in the world economy after the global financial crisis, reinforced by the coronavirus crisis and geopolitical turmoil, has led to the emergence of new trends in the international dynamics of capital. Decreasing economic growth rates, slowing globalisation, and growing economic and geopolitical uncertainty have all resulted in a reversal of the established trends.

In previous decades, the growth of global capital exports kept pace with or outpaced global GDP, but the opposite has been happening in 2010s and 2020s. As a result, global capital exports, which fell sharply in the wake of the 2008 global crisis, have not reached pre-crisis levels ($7.4 trillion in 2022 vs $10.3 trillion in 2007).

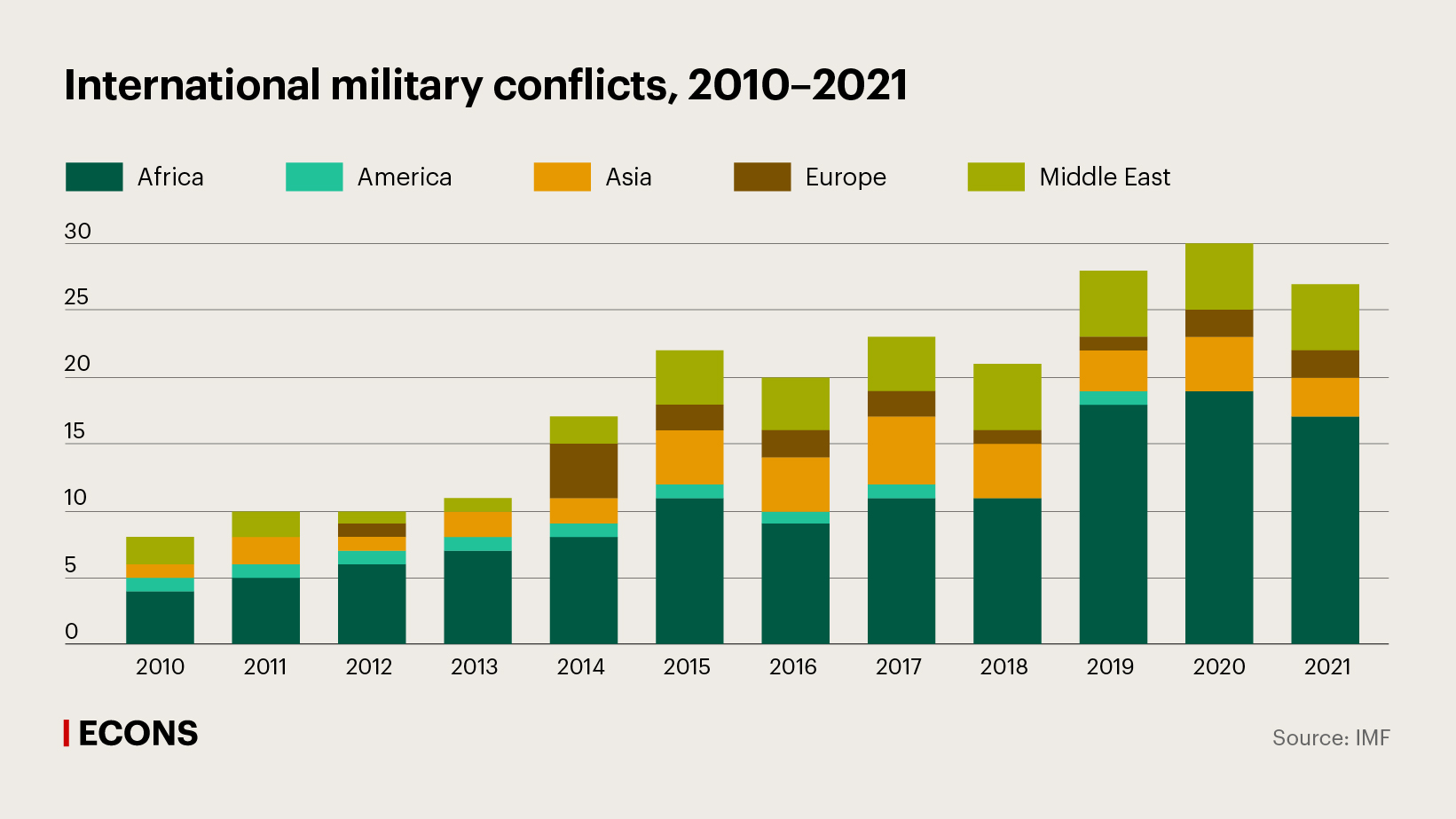

The international capital flows and international trade lags behind the growth of world GDP is often interpreted as a reversal of earlier trends in the globalisation of the world economy. This coincides with the opinion of IMF experts expressed in early 2023 about the process of geo-economic fragmentation that has begun in the world. This process is often driven by strategic considerations related to political and economic security, and it is largely due to the growing number of armed conflicts in the world – a trend that had formed even before the current military operation in Ukraine. The number of military conflicts has nearly tripled in the past decade.

In addition to the ‘impossible trinity’ (a concept stating that it is impossible to have all three of free capital movement, a fixed foreign exchange rate, and an independent monetary policy at the same time), it has been suggested that there are other trilemmas of international capital movements in which the absence of capital controls does not allow other objectives to be achieved simultaneously. Such objectives include financial stability, countries’ concerns about national sovereignty, the degree of their commitment to the established world order, and their focus on solving internal political problems – that is, these objectives mostly pertain to political economy.

Increasing geopolitical risks have put the clear, if not the main, brake on international capital flows. The dynamics of such capital flows are the subject of our review published in Voprosy Ekonomiki journal. Geopolitical relations, as emphasised by IMF experts, can influence the direction of cross-border capital flows by affecting investor behaviour, as market participants tend to invest less capital in countries whose views on foreign policy differ from those in the countries of origin of the capital. Investors are concerned about financial constraints, information asymmetry, general distrust, or the expropriation of their capital in receiving countries with ‘different views on foreign policy’.

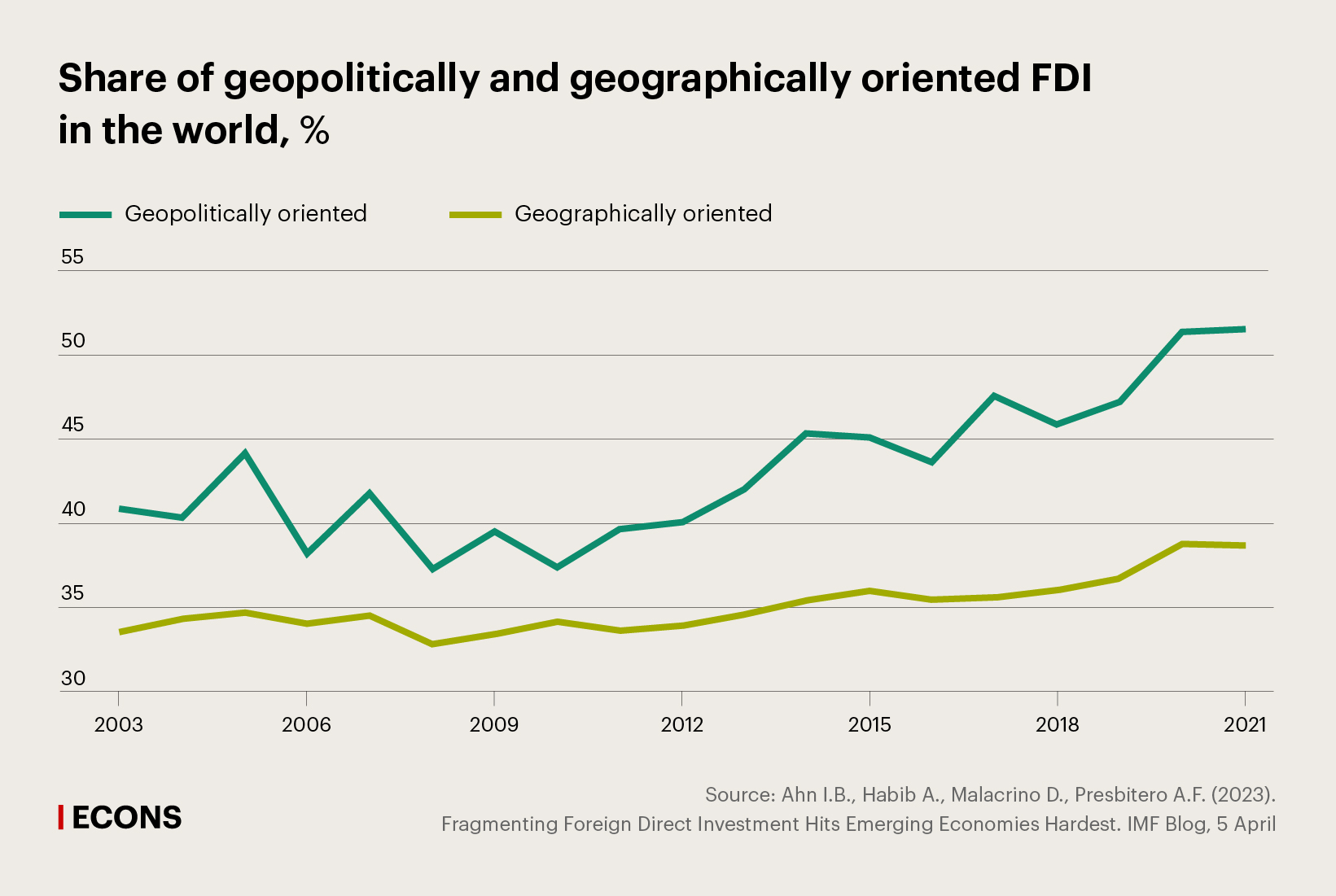

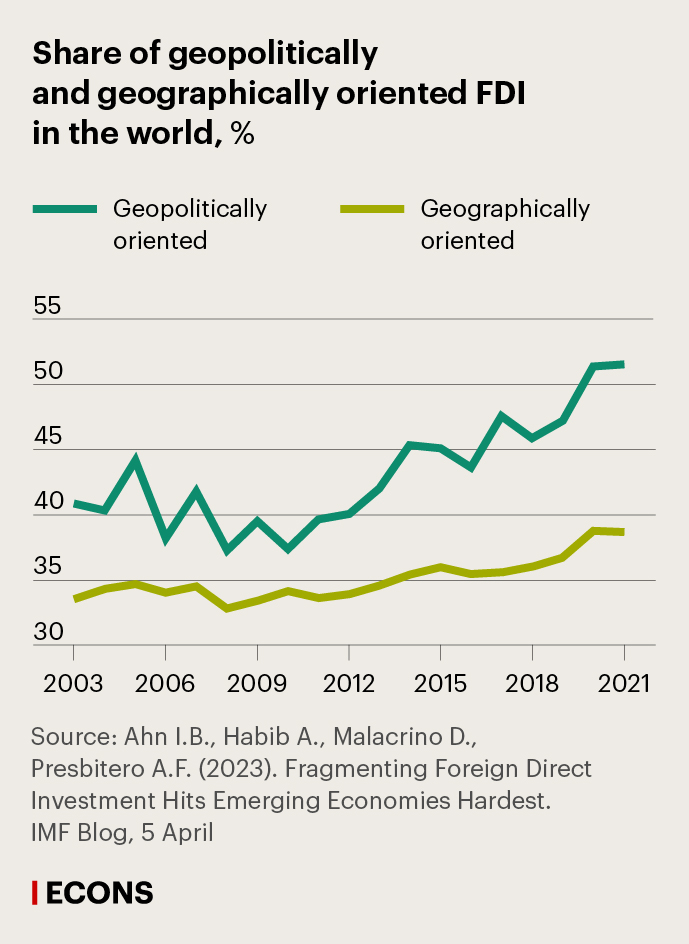

Data on foreign direct investment (FDI) show that geopolitical and geographical distancing – the orientation of investment towards allied or geographically close countries – has intensified since around 2014, the year in which the number of international military conflicts began to increase.

Such distancing is encouraged by the governments of various countries, primarily to make global value chains more resilient. Reshoring, the transfer of these value chains or parts of them to their home countries or closer to them (in the latter case, it is called nearshoring), or friendshoring (the transfer of value chains to friendly countries) are initiated to this end.

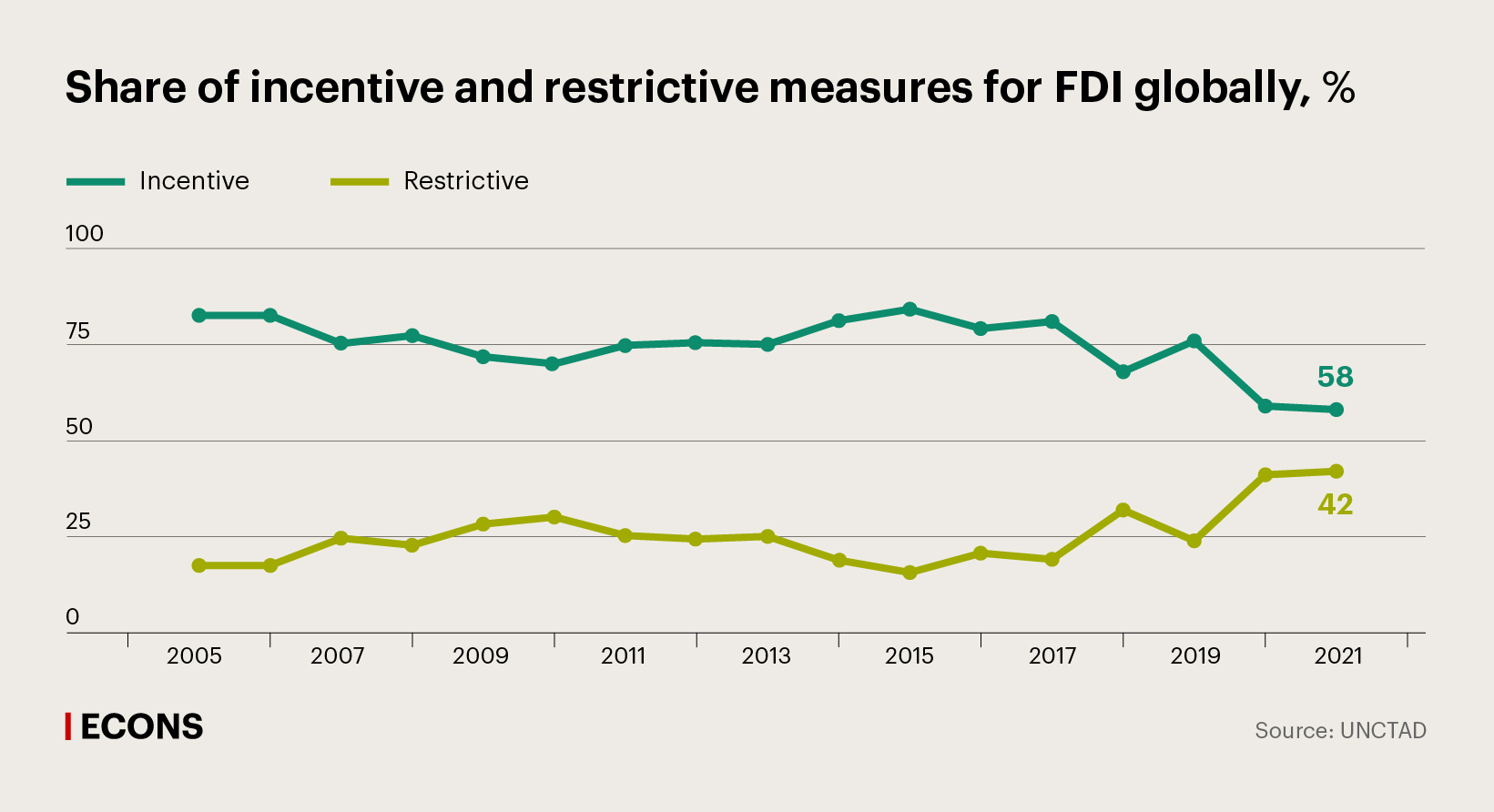

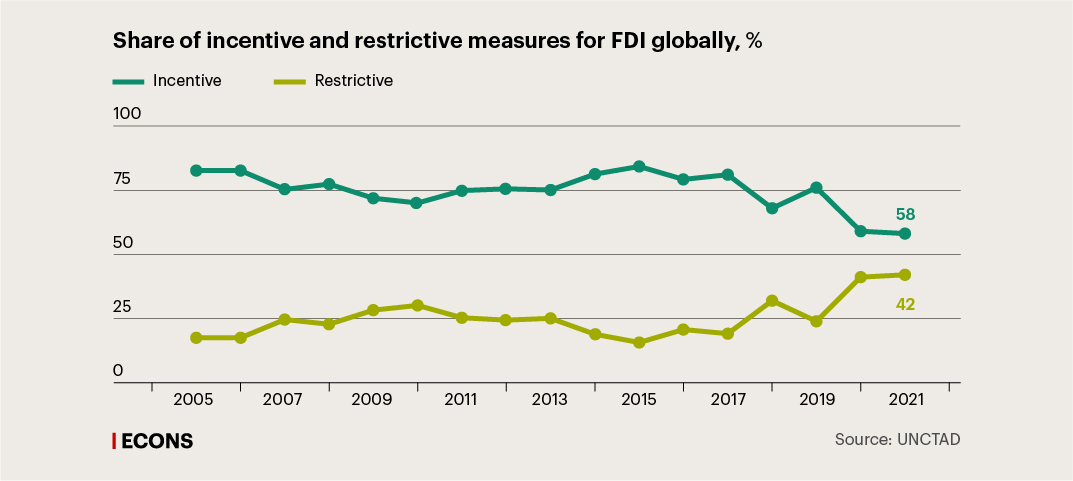

Since the middle of the last decade, the measures taken in relation to FDI in the entire world have increasingly been restrictive rather than encouraging.

During the same period, the number of countries that screen FDI for national security purposes began to increase. In 1995, there were only three such countries; by 2022, the number had risen to 37, primarily due to 28 developed countries, including most of the EU countries, the US, Canada, Japan, South Korea, and Australia. Generally, this can be interpreted as part of the sanctions campaign conducted by the developed countries – major capital exporters – against many developing countries. According to the IMF, the share of jurisdictions subject to financial sanctions alone increased from 22% to 57% between 2010 and 2022.

Geography of international capital flows

Mutual investments by developed countries continue to account for the vast majority of capital exports and imports globally, but the share of developing countries in both capital exports and imports is gradually increasing (from 10% to 19% and from 9% to 23%, respectively, over 2000–2021, according to IMF data), while the share of developed countries is declining. However, the leaders of capital flows are also changing within both groups of countries.

From 1990 to 2021, among the developed countries, the United States retained its leadership as the top capital exporter, but the ‘Asian tigers’ (South Korea, Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Singapore) and Ireland (where most of the European headquarters of American multinational corporations are located) displaced Germany, France, the United Kingdom, and the Benelux countries, which had previously followed the US, while Japan dropped out of the list of leading capital exporters. Among the developing countries, China became the undisputed leader in capital exports, followed by India, Russia, Brazil, and Saudi Arabia by a wide margin. The changes in the leaders by capital imports were characterised by a similar trend.

Another notable trend in recent years has been growing international coordination to strengthen control over tax evasion through foreign jurisdictions. This is due, inter alia, by the fact that most countries are not willing to tolerate the withdrawal of a significant part of investments to offshore and transit countries.

Assuming that international capital flows worldwide are still driven by the GDP developments in major capital exporters and importers, that these capital flows continue to lag behind the pace of global trade, and that geopolitical tensions in the world persist, we can assume that capital flows will actually be at the level of 2021–2022 in the coming years, if calculated at constant prices, that is, they will grow only at the inflation rate.

Based on the ongoing defragmentation of the world economy, we can also assume a slight increase in the share of developed countries in capital exports and imports and a reduction in the previously growing share of developing countries, which will become more risky from the point of view of Western investors and which will not be able to compensate for this with mutual investments.

Russia and international capital flows

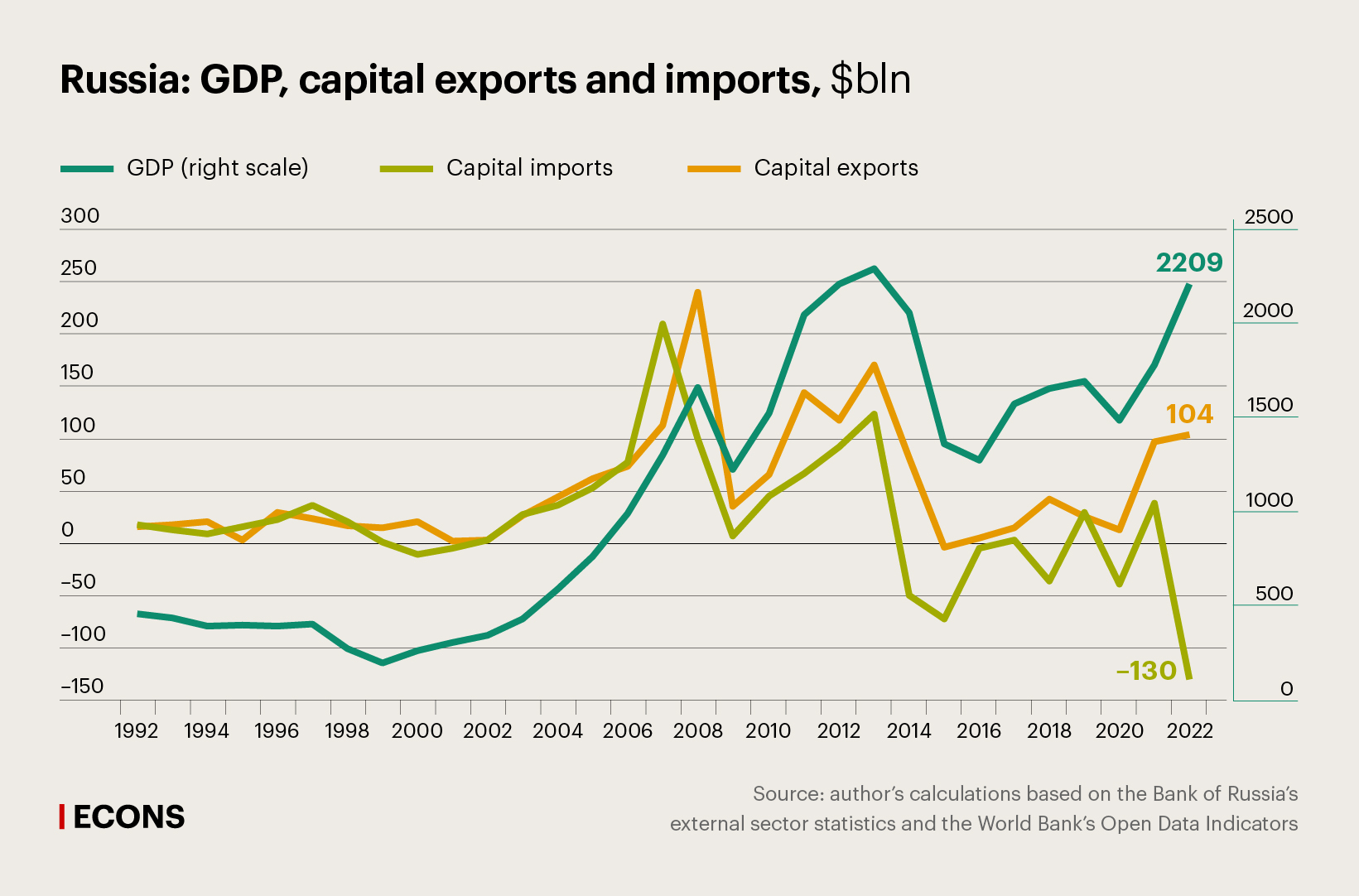

Over the past 30 years, Russia has seen both general and specific trends in its participation in international capital flows.

- Before 2008, the growth of capital exports and imports outpaced GDP, while after 2008, it lagged behind GDP, as in the world economy as a whole.

- Capital exports usually exceeded capital imports (in 21 out of 31 years), which is typical for countries with current account surpluses, which Russia had in all these years, except for 1997.

- In 2022, there was a turning point in capital imports caused by the Western sanctions and falling GDP.

In 2022, when Russia’s foreign economic position changed drastically, capital exports from the country continued, but not in all forms: there was a decline in direct and portfolio investments accumulated abroad, but there was simultaneously a jump in other investment exports, which was due to the increase, especially in 2022 Q1, in cash currency and deposits, loans, credits, and other debts.

In 2022, other investment exports were characterised by the following trends:

- There was a sharp decline in net foreign currency sales by exporters, to $15.7 billion (link in Russian) in December 2022. By comparison, exports of goods in that month may have been around $40 billion (based on Bruegel data), and three quarters of this amount was paid in foreign currency. This led exporting companies to accumulate foreign currency in their accounts abroad, and the transfer of funds from such accounts to Russia was hampered by the disconnection of most Russian banks from SWIFT.

- The foreign assets of Russian banks increased by approximately $30 billion (link in Russian) despite the sanctions.

- Funds deposited by individuals in foreign banks doubled in ruble terms in 2022 to 4.5 trillion roubles (from $31 billion to $67 billion at the average annual exchange rate).

Capital exports continued in 2023 Q1 and 2023 Q2, although in lesser amounts than in 2022 Q1 and 2022 Q2 ($24.9 billion vs $67 billion, according to the Bank of Russia’s estimates and the author’s calculations).

As for capital imports, there was major disinvestment in 2022, that is, a decline in the amounts of capital previously imported in all forms, driven by the exit of foreign companies from Russia. Disinvestment continued in 2023 Q1 (by $13.3 billion, according to calculations based on the balance of payments of the Russian Federation).

The flight of foreign capital and the capital exports of Russian residents together resulted in a record outflow of $237.5 billion in 2022, the largest annual capital outflow in the last three decades. This is not counting the part of official reserves blocked abroad ($200–300 billion, according to various estimates) or other assets of Russian residents.

In addition, in 2018–2020, investments made by foreign owners and joint investments made by both foreign and Russian owners accounted for a notable share of all annual fixed capital investments in Russia, from 12% to 15% (link in Russian), about the same as in 2011–2014.This made foreign investments – combined with the new technologies they brought – an important source of economic growth and technological progress in the Russian economy.

Russia and restrictive measures

In 2022–2023, as part of the new wave of Western sanctions, in addition to the disconnection of most Russian banks from SWIFT and the freezing of the Bank of Russia’s assets in Western countries, most of the assets of Russian investors in Euroclear and Clearstream, mainly in the form of foreign securities, totalling $6 billion (link in Russian) (or perhaps more) were blocked. The foreign assets of Russian individuals subject to Western sanctions were also frozen, totalling $58 billion, according to the REPO (Russian Elites, Proxies, and Oligarchs) Task Force set up by the Western countries to identify these assets.

As for the assets of Russian corporates blocked abroad, there are only estimates for certain companies. In particular, VTB’s assets blocked abroad amounted to about $8 billion (link in Russian). The Western sanctions have also forced certain Russian companies, primarily oil producers, to sell part of their assets in Western countries. For example, in 2023, LUKOIL sold its oil refinery in Sicily for about €1.5 billion (link in Russian) due to the sanctions on oil supplies to its three refineries in the EU. Overall, by the end of 2022, LUKOIL, Rosneft, and Gazprom had lost control (link in Russian) over a number of their foreign refineries. Indicatively, the German government seized (link in Russian) three oil refineries partially owned by Rosneft and the German subsidiary of Gazprom (link in Russian).

Russia has begun to pursue a policy of restraining (link in Russian) such disinvestment, primarily using C-type accounts, in relation to foreign investors from unfriendly states who had previously invested their funds in the Russian economy and now wish to withdraw these funds. This has had an effect. Indeed, according to a study, only fewer than 9% of the 2,405 firms in Russia owned by EU and G7 residents had left the country. However, these were mostly large companies, and as a result, in 2022 and 2023 Q1, the foreign capital accumulated in Russia decreased by a third (from $1.17 trillion to $772 billion, according to the Bank of Russia), mostly due to the loss of direct and portfolio investments. In addition, in April 2023, Russia took a new step by imposing external administration (link in Russia) on the assets of Finland’s Fortum and Germany’s Unipro in retaliation for similar actions taken in the EU against the assets of Rosneft and Gazprom.

What’s next?

By early 2022, up to three quarters of direct investments imported into Russia and two thirds of portfolio investments exported from Russia involved offshore and Western transit countries, indirectly reflecting the ‘turnover’ of Russian capital. The percentage of investments made by developing countries in Russia is not significant: for example, China accounts for 0.5% of incoming investments, and India’s share is even smaller.

It is likely that Russia cannot count on the previous level of capital imports in view of the projected low performance of the global and domestic economies, especially due to the growing geopolitical strain in its relations with the Western countries. The ‘turnover’ mechanism, which used to provide the main inflow, may now hinder it, as the inflow came mainly from the developed countries and offshore areas, which are under growing pressure from the Western countries. The relatively small amount of Chinese and Indian investment in Russia suggests that investors from developing countries have shown little interest in investing in the Russian economy, and their investment appetites are unlikely to increase significantly in the coming years.

The potentially weak inflow of new foreign capital into Russia, combined with the continued disinvestment of previously imported capital, will lead to a reduction in accumulated foreign investment in the country in the years to come. This will have a tangible impact on economic growth and technological progress in Russia.

The dynamics of capital exports by residents from Russia will depend on two main factors. On the one hand, uncertain prospects for Russia’s development will continue to urge Russian investors to export at least part of their capital to foreign countries to protect it (to create ‘safety deposits’ abroad). The substantial current account surplus forecast by the Bank of Russia and the Russian Ministry of Economic Development will provide the foreign currency resources needed for such exports in the next few years. Meanwhile, the limited capital control existing in Russia will offer opportunities to withdraw capital, just as in 2022, albeit not in all forms nor across all channels.

On the other hand, this withdrawal will be hampered by the anti-Russian attitude of the Western countries, while Russian investors may find it risky to invest capital in developing countries in tangible amounts. Given the effect of these opposite trends, we can expect that capital exports by residents from Russia will continue in the short term, but in much smaller amounts than in 2022.

The full article is published in Voprosy Ekonomiki, No. 9, 2023.