For all the abundant loans and grants available from numerous international financial institutions (IFIs) to developing countries, there are still scarce open-access aggregate data to detail their volumes and objectives. With each organisation only reporting on its own projects and to its own classification standards, data alignment is difficult.

The real picture may be clear from special databases on this type of finance. The following four tables are most informative: Total Official Support for Sustainable Development (TOSSD), maintained by the OECD, External Debt Database of the World Bank, GFSN Tracker of the Global Policy Development Center of Boston University and UN Conference on Trade and Development, and AidData, compiled William & Mary’s Global Research Institut and Brigham Young University. However, these databases have different timespans and sources of information, and their samples of donors and countries are also different. In addition, they leave out the intense operations of numerous development agencies that work with developing economies. There are no open-access data of this kind accessible to government agencies of recipient countries.

Experts at the Eurasian Fund for Stabilisation and Development (EFSD) systematised the silos of data on sovereign financing provided by major IFIs to the 11 Eurasian countries (see Box) to track trends in international lending and the way it changes in times of crises. The EFSD SFD sovereign financing database since February 2023 is available online and updated quarterly.

IFIs provide funding for crisis management and development needs. The wide toolset of sovereign financing of IFIs can be divided into four types:

- stabilisation loans, intended to restore macroeconomic and financial stability in times of financial and economic crises or to counter their consequences (such stabilisation programmes often require that recipient countries implement a set of economic policy measures)

- investment loans, aimed at the development of physical and social infrastructure, such as transport, the power sector, and social services, including improvements in and wider access to medical and educational services

- technical assistance programmes involving the financing of projects to improve the quality of economic institutions and transfer expertise; and finally

- grants, free funding from IFIs for a wide range of initiatives and activities.

Our assessments are conservative since the database relies only on public sources. Nevertheless, it seeks to be as complete as possible.

Scale of financing

Between 1 January 2008 and 1 January 2023, IFIs and development agencies operating in the Eurasian region closed about 4,000 transactions worth about $95 billion.

Over the 15 years covered by the database, the existing IFOs that provide sovereign financing to the Eurasian region have seen significant grown in operations, and new IFIs have emerged. In particular, in 2009, six states (Russia, Armenia, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan) established the Eurasian Fund for Stabilisation and Development, which serves (link in Russian) as the regional financial vehicle of the Global Financial Safety Net. In addition, in 2014, BRICS countries (Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa) founded the New Development Bank (NDB). In 2015, at the initiative of China, the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank was set up, of which major shareholders are, beyond China, South Korea and Turkey. Besides IFIs, the region is marked by intense operations of development agencies.

Based on the analysis, IFIs account for 75% of the volume of sovereign financing transactions made since 2008 in the 11 Eurasian countries in the database, with the remaining 25% attributed to development agencies. This comes as a result of the greater scale of operations and budgets of IFIs and higher transparency in the operations of international organisations, with almost all IFIs publishing their open-access databases on complete and current projects.

The new EFSD SFD database discloses not only the main lenders and borrowers of the region, but also the workings of the Global Financial Security Network (link in Russian). Although most resources of IFIs are spent on investment projects in the region, in times of crisis, international financial institutions expand the number of programmes intended to restore macroeconomic and financial stability, our analysis shows.

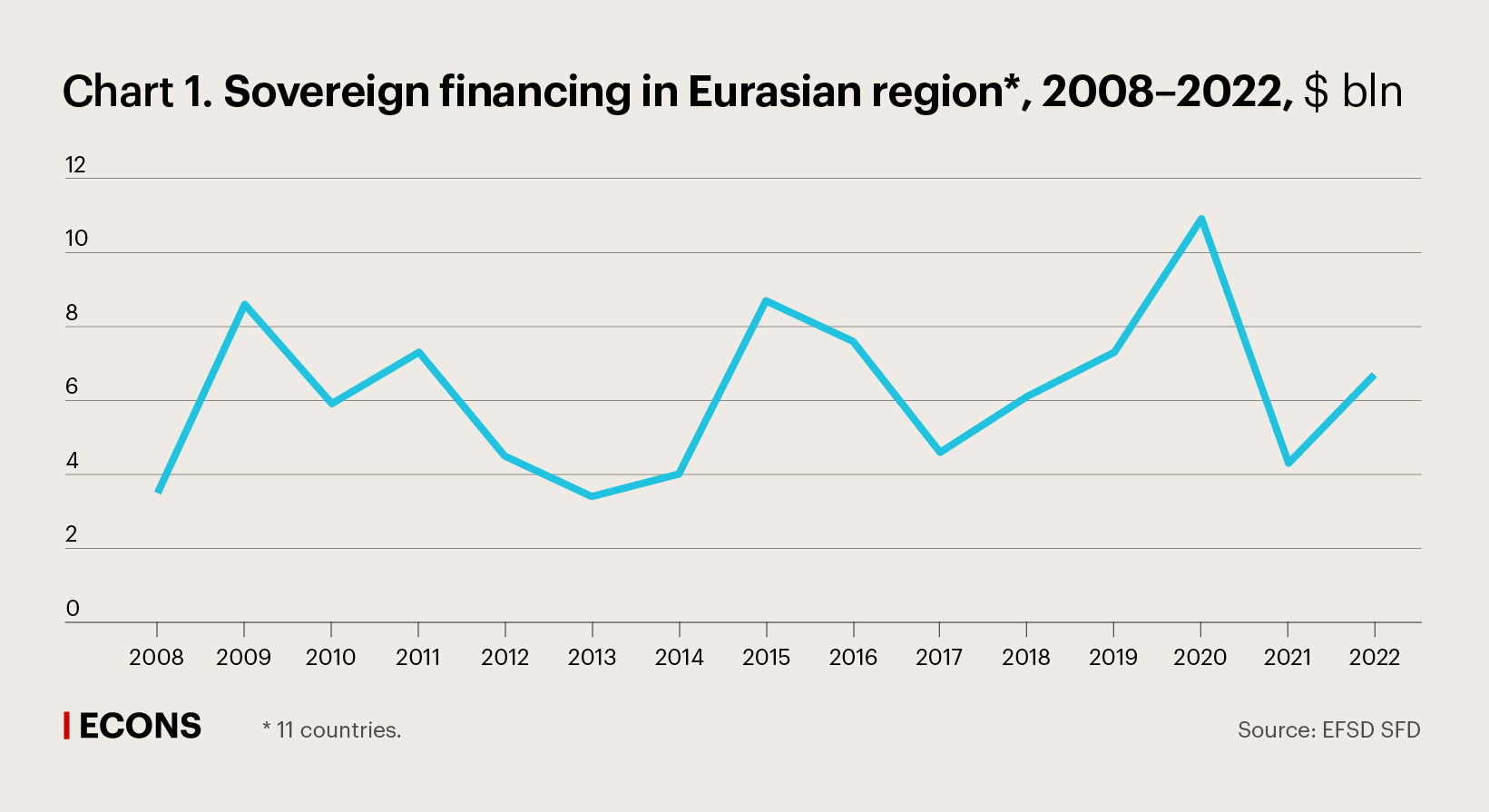

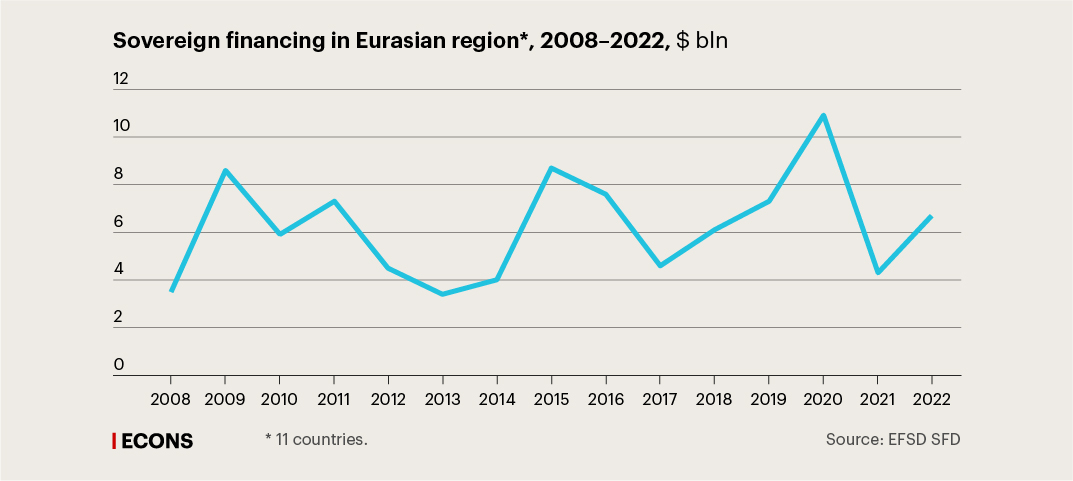

Evidently, sovereign lending peaked in the years of crises: in 2009 ($8.6 billion), 2015 ($8.7 billion) and 2020 ($10.9 billion). This can be explained by rapidly expanding crisis response measures aimed at addressing the global financial and economic crisis of 2008–2009, the 2015 regional crisis in Eurasian economies following the collapse of oil prices and the ruble devaluation in 2014, and the global pandemic crisis of 2020 respectively (see Chart 1).

The region’s total stabilisation loans worth $33 billion accounted for a little more than a third of all financing approved from 2008 to January 2023. Development banks were prominent players in crisis management support, having provided half of such loans ($17.3 billion).

Whether international development banks should allocate a significant part of their resources for stabilisation support is an open and rather controversial issue. On the one hand, crises come with long-term scarring effects. The number of transactions approved in 2021 was the lowest since 2008 – that can probably be explained by the large number of projects that IFIs and development agencies had approved during the global crisis caused by the pandemic – which organisations and countries did not have the time to complete in 2021.

On the other hand, the portfolios of IFIs focused on Eurasian countries are overall dominated by investment loans, which, compared to crisis management support, are distributed more evenly over time. They account for over $55 billion – more than half of the funding approved by IFIs and development agencies for the region. This is driven by the high demand for infrastructure and human capital investments. The EFSD SFD database shows priority projects by sector, including those aimed at improving economic policy and public administration, on the one hand, and the development of basic infrastructure (essentially transport and energy), on the other hand.

Technical assistance programmes involving the transfer of expertise are the largest tool of sovereign financing in terms of number of operations (2,900+ operations or almost 75% of the total) and the smallest in terms of volume (worth about $0.8 billion). Technical assistance projects differ significantly in duration and content – from short-term consultation workshops to multi-year projects related to structural transformations in the economy.

Key lenders and borrowers

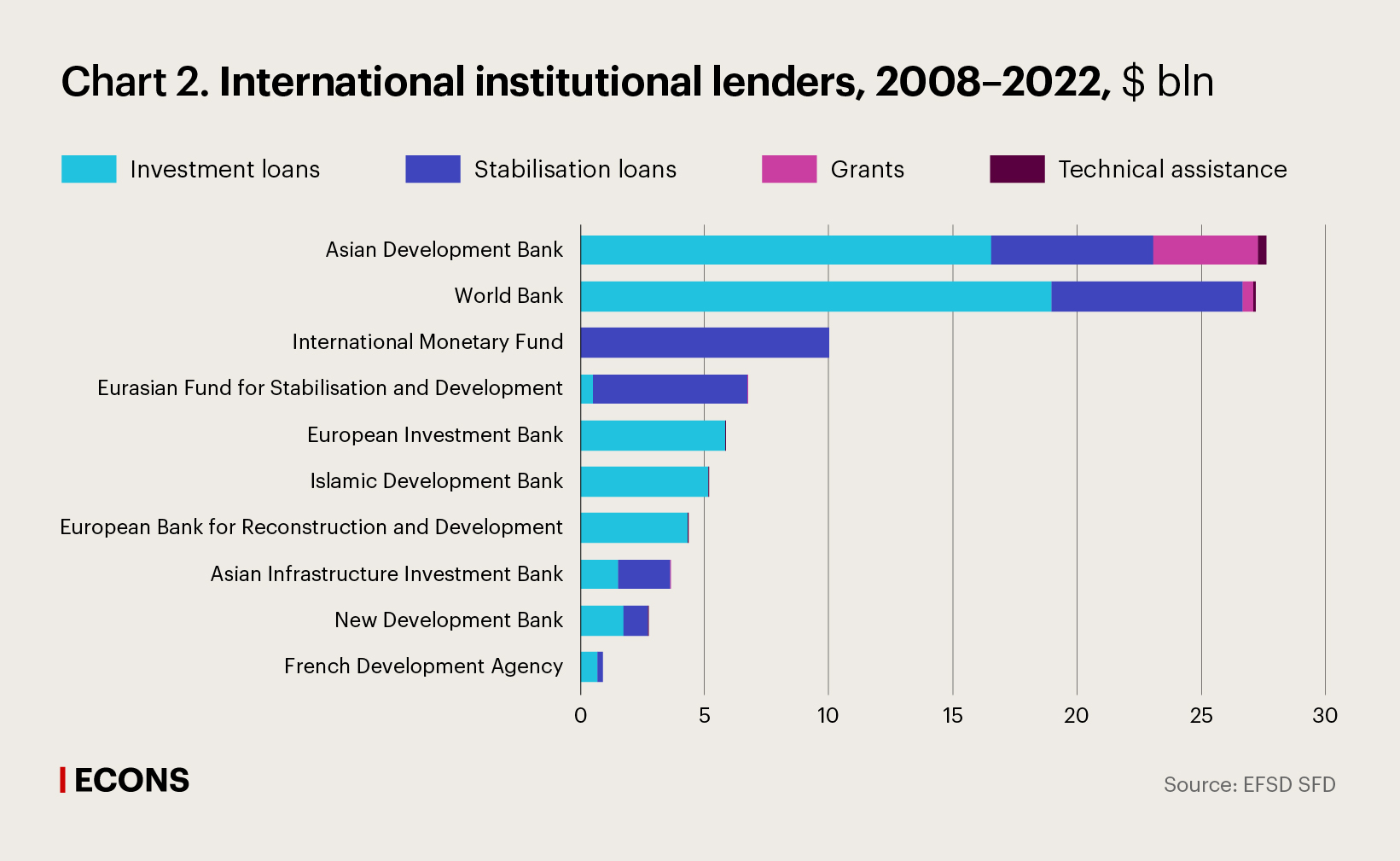

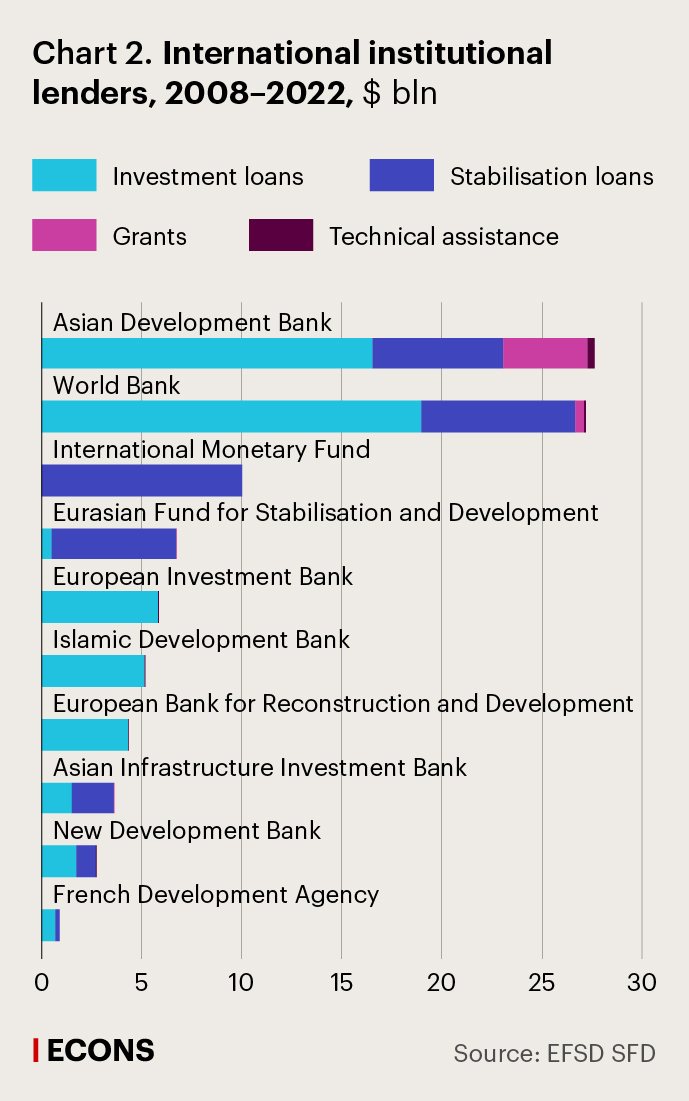

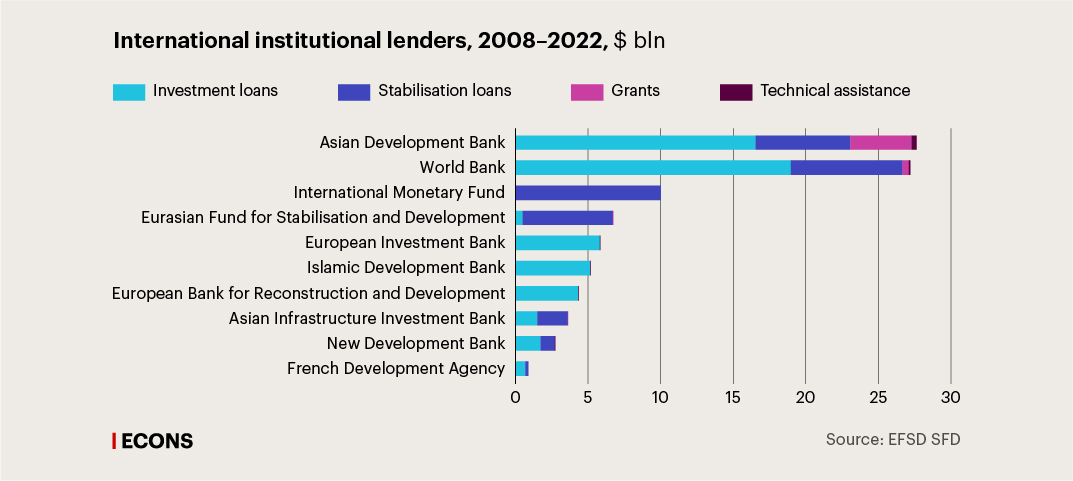

The leaders in terms of approved funding are the Asian Development Bank (ADB), the World Bank, the IMF and the EFSD, collectively accounting for 75% of the region’s total financing since 2008 (see Chart 2).

There are a number of reasons behind this. First, this is the larger number of countries in the region that the IMF, the World Bank and the ADB work with. Second, their operations cover the entire (or almost the entire in the case of the EFAD) time span of the EFSD SFD database, unlike other organisations operating since 2008.

However, the last five years are clearly marked by certain changes. The first top positions are invariably held by the World Bank ($11.8 billion) and the ADB ($11.4 billion), but they are followed by the European Investment Bank ($3.3 billion), the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB, $3 billion) and the New Development Bank (NDB, $2.7 billion). Newcomers to IFIs, the AIIB and the NDB have become active providers of financing to countries for infrastructure development. They allocated significant resources as stabilisation support during the COVID-19 crisis.

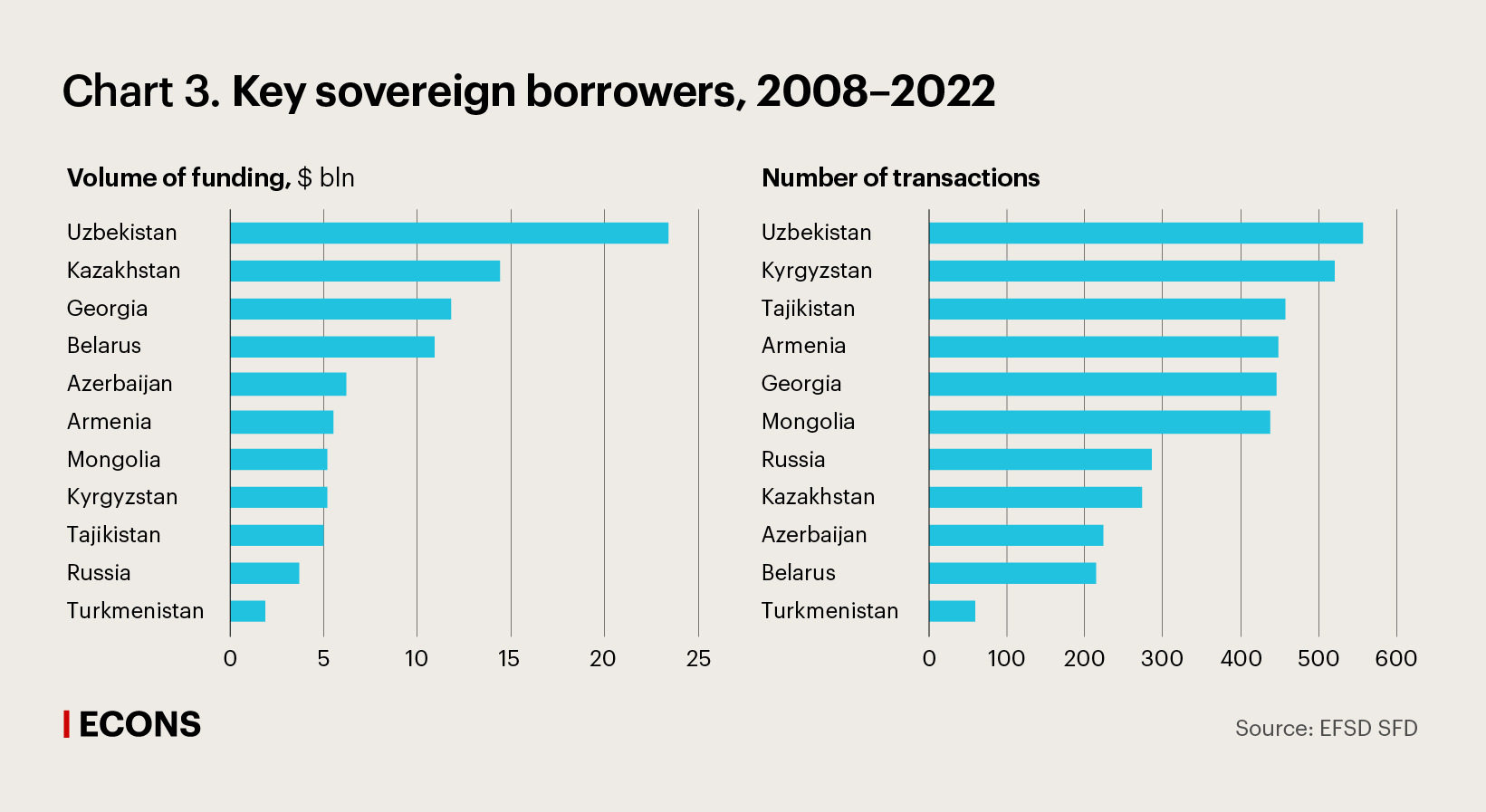

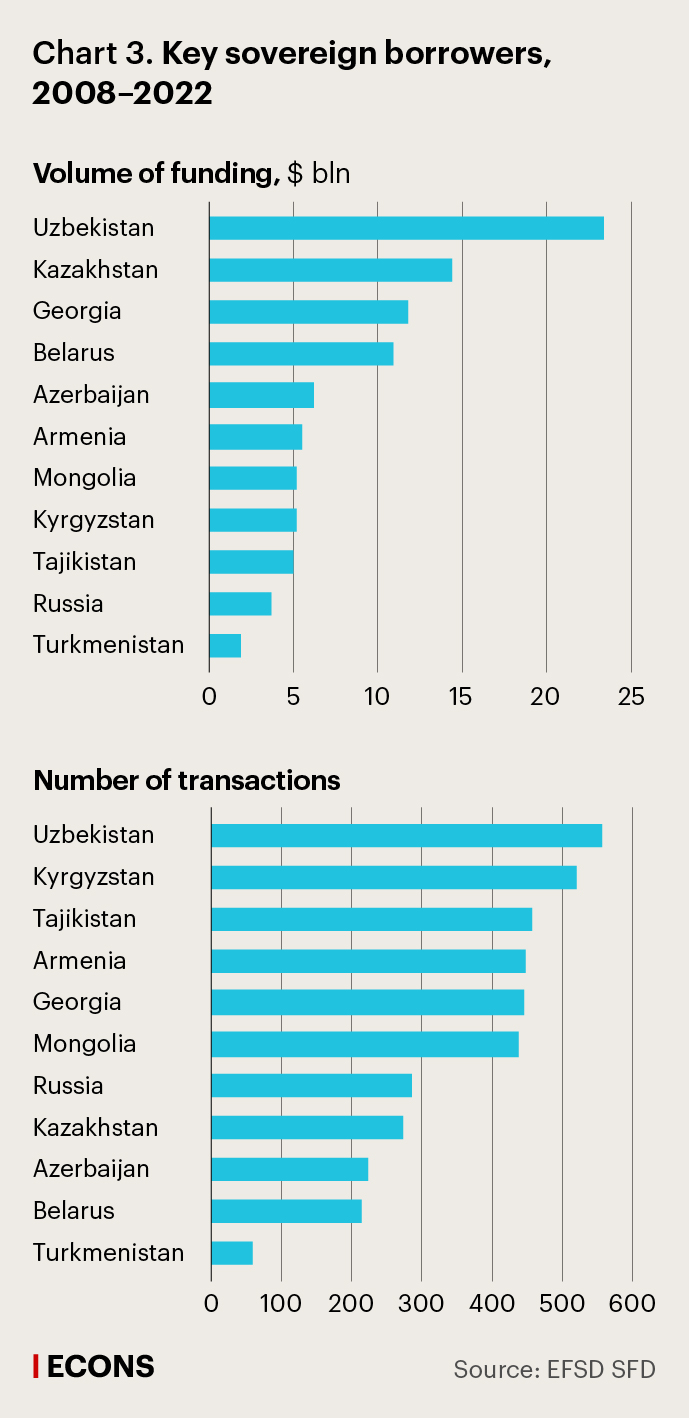

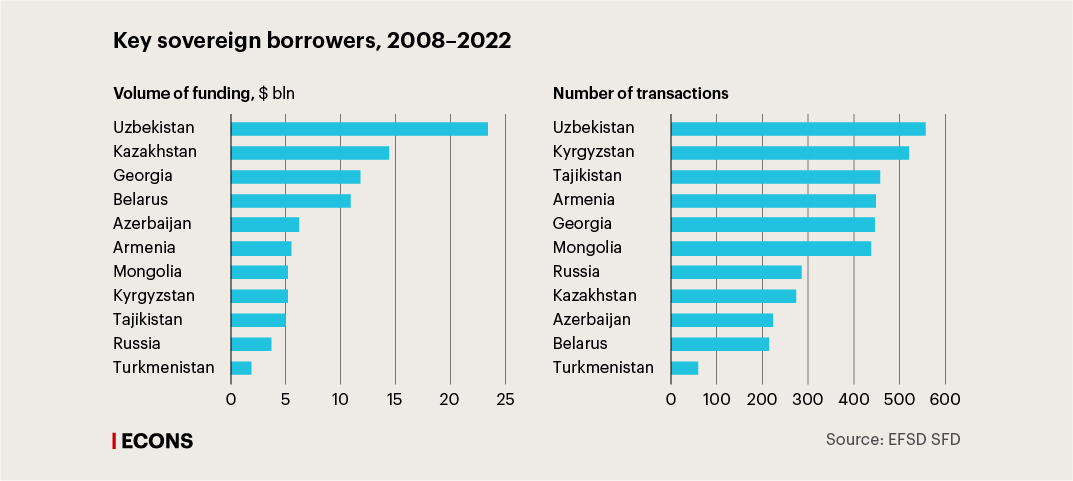

Of the sovereign borrowers, Uzbekistan ranks top by the number of transactions and the volume of funding ($23.4 billion, or almost 25% of the region’s total financing). The other leaders by the number of operations are Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan, but they are at the bottom of the list by the volume of approved financing. Kazakhstan, sitting in second place in terms of funding volumes, accounts for a smaller number of transactions (see Chart 3).

Based on the quantitative analysis of the EFSD SFD database, three key trends stand out in sovereign financing.

First, approved funding from IFIs peaked in crisis years, at a time the number of macroeconomic stabilisation programmes was on the rise, whereas investment projects are more evenly distributed over time.

Second, multilateral development banks play a major role in providing stabilisation support (link in Russian).

And third, one of the focal areas of sovereign financing is capacity development. The enormous number of technical assistance projects is testament to the urgent need of regional countries for improving skills and competencies, as well as for structuring and supporting investment projects.

.jpeg)