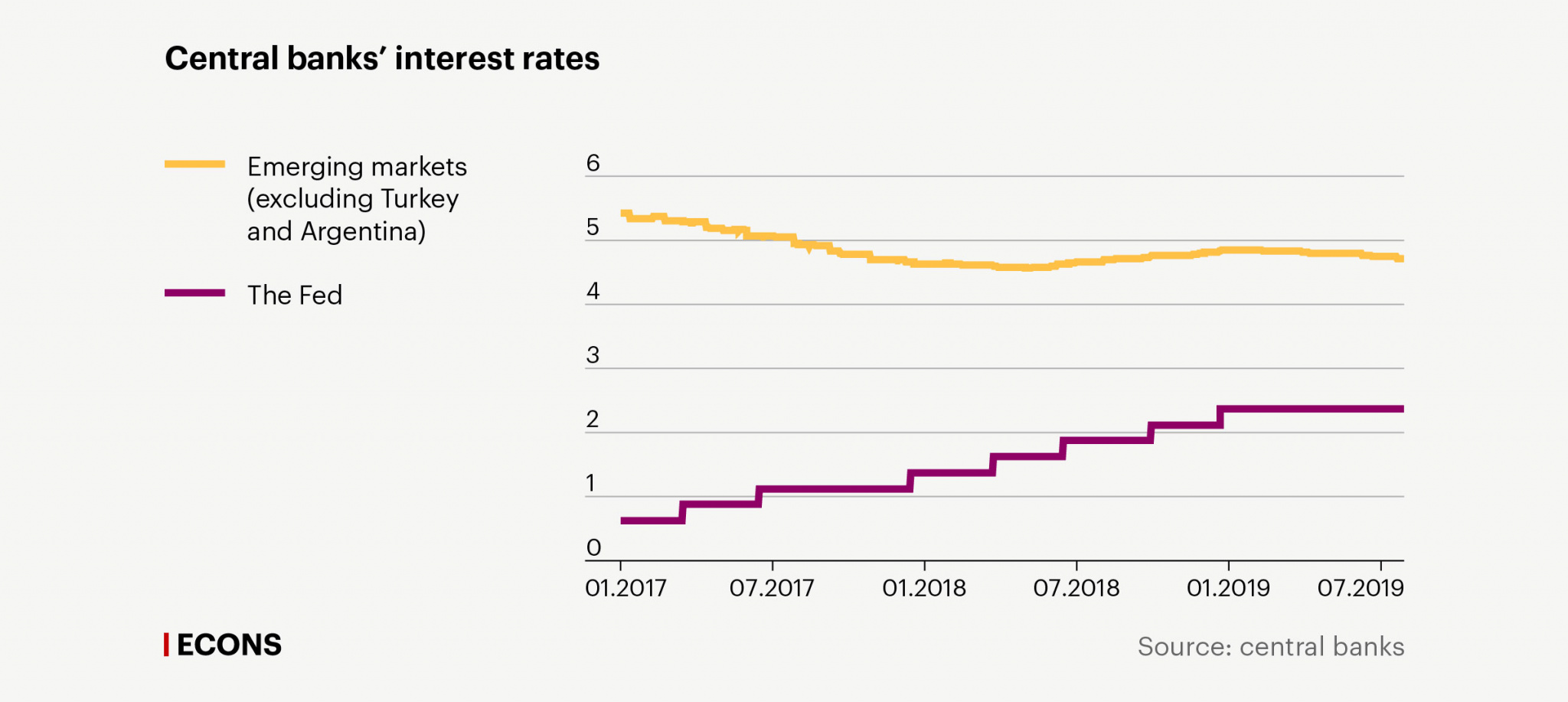

In the first half of 2019, almost all assets in global markets showed positive trends: equity markets grew in both developed and emerging economies; in the majority of countries, bond yields decreased in both national and foreign currencies; the risk premium of emerging markets went down; and volatility returned to early/mid 2018 levels. This improvement in financial conditions on global markets was the result of a shift in leading central banks’ policies: they chose looser monetary policy over monetary policy normalization (i.e. raising interest rates that had remained extremely low for almost a decade). This shift was driven by increasingly obvious signs of a global economic slowdown and by the serious risks presented by the US – China trade dispute, which was not resolved at the G20 summit in Osaka. In developed economies, inflation is still below central banks’ targets, and slower growth leads to lower inflationary pressure, all other things being equal. This is one of the reasons central banks in developed countries are acting as they are.

The global economic slowdown is currently a key threat to global financial markets. There is a real risk that circumstances will change for the worse and emerging markets will face even larger capital outflow. Nevertheless, the events of 2018 – massive capital outflow from emerging markets and increased bond yields – are unlikely to repeat themselves, for several reasons:

Chart 1.

Central banks’ interest rates

The Fed

Emerging markets (excluding Turkey and Argentina)

6

5

4

3

2

1

0

01.2017

07.2017

01.2018

07.2018

01.2019

07.2019

Source: central banks

The Fed

Emerging markets (excluding Turkey and Argentina)

6

5

4

3

2

1

0

01.2017

07.2017

01.2018

07.2018

01.2019

07.2019

Source: central banks

Emerging markets

(excluding Turkey and Argentina)

The Fed

6

5

4

3

2

1

0

01.2017

07.2017

01.2018

07.2018

01.2019

07.2019

Source: central banks

However, the steps central banks take could prove insufficient for preventing global economic slowdown. Factors that may compound the recession and make further recovery difficult persist:

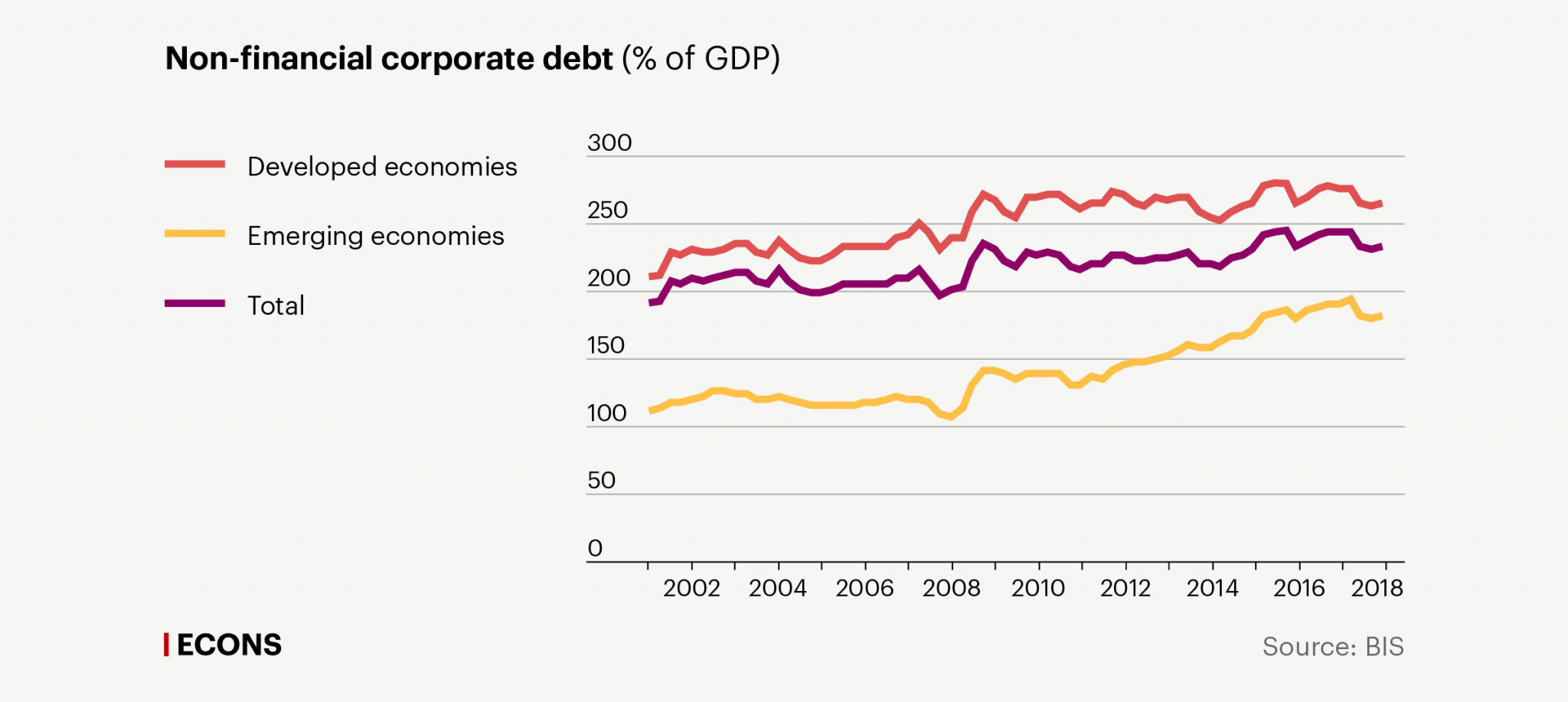

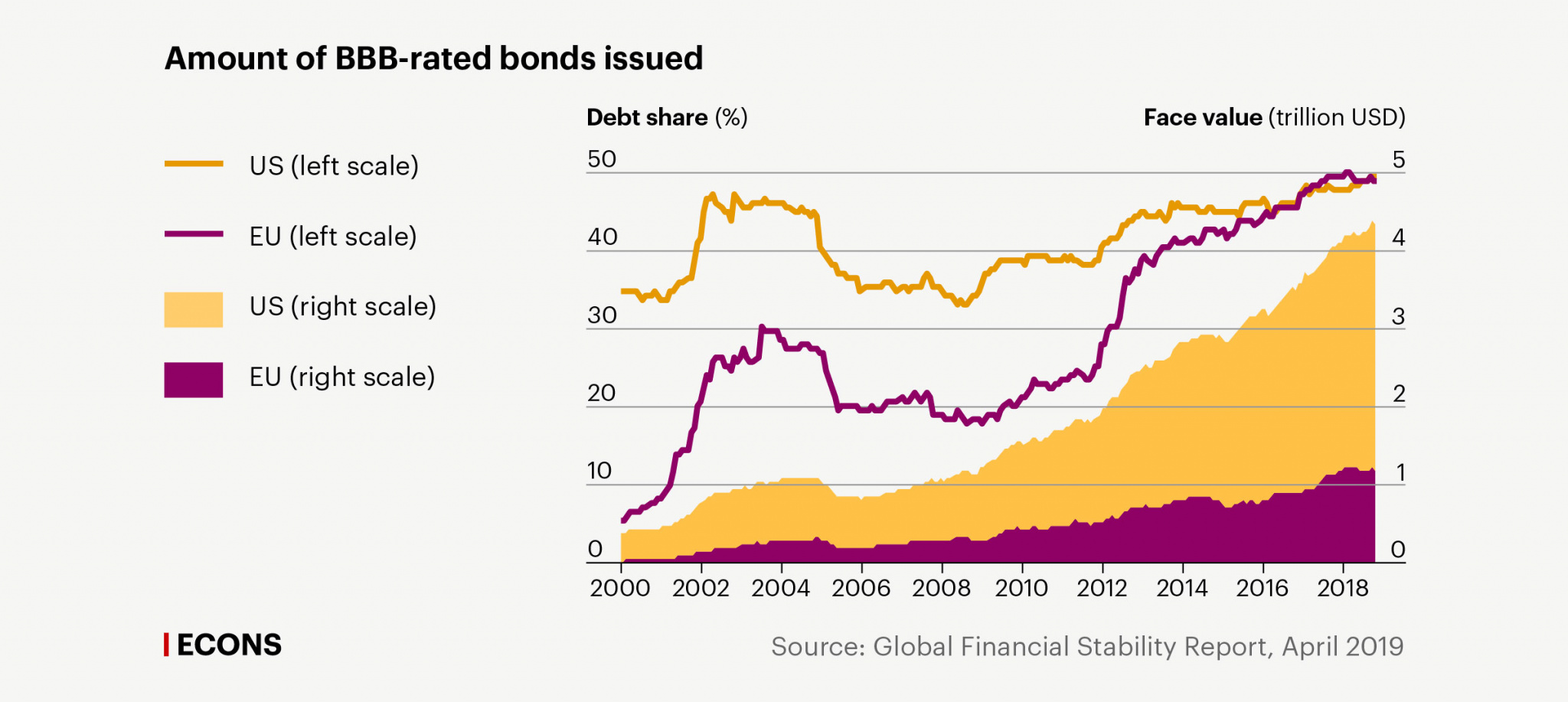

1. Substantial non-financial corporate debt

Slower global trade growth and potential further global economic slowdown are undermining the prospects for corporate profit growth. This factor could play a crucial role in asset reevaluation and increased borrowing costs for business. The lenient financial conditions that supported the economy after the global crisis resulted in record-high corporate debt (see Chart 2). Moreover, recent equity offerings are characterized by lower ratings, while issuers have higher leverage; at the same time, the proportion of BBB bonds in investment-grade debt has risen (see Chart 3).

Chart 2.

Non-financial corporate debt (% of GDP)

Total

Developed economies

Emerging economies

300

250

200

150

100

50

0

2001

2002

2003

2004

2005

2006

2007

2008

2009

2010

2011

2012

2013

2014

2015

2016

2017

2018

Source: BIS

Developed economies

Total

Emerging economies

300

250

200

150

100

50

0

2002

2004

2006

2008

2010

2012

2014

2016

2018

Source: BIS

Developed economies

Emerging economies

Total

300

250

200

150

100

50

0

2002

2006

2010

2014

2018

Source: BIS

In the event of another global recession, reevaluation of companies’ prospects – in the real and financial sectors as well as the private and public sectors – will lead to higher borrowing costs, refinancing problems, and massive downgrades. Lack of room for manoeuvre in certain leading countries’ fiscal policy (due to substantial public debt and/or weak political will) and monetary policy (due to low interest rates) could intensify the negative impact of poor credit quality on economic performance. As a result, economic recovery could take a relatively long time.

Chart 3.

Amount of BBB-rated bonds issued

US (left scale)

US (right scale)

EU (left scale)

EU (right scale)

Debt share (%)

Face value (trillion USD)

50

5

40

4

30

3

20

2

10

1

0

0

2000

2002

2004

2006

2008

2010

2012

2014

2016

2018

Source: Global Financial Stability Report, April 2019

US (left scale)

US (right scale)

EU (left scale)

EU (right scale)

Debt share (%)

Face value (trillion USD)

50

5

40

4

30

3

20

2

10

1

0

0

2000

2002

2004

2006

2008

2010

2012

2014

2016

2018

Source: Global Financial Stability Report, April 2019

US (left scale)

EU (left scale)

US (right scale)

EU (right scale)

Face value

(trillion USD)

Debt share (%)

50

5

40

4

30

3

20

2

10

1

0

0

2002

2006

2010

2014

2018

Source: Global Financial

Stability Report, April 2019

2. High volatility of capital inflow in emerging economies

According to the IMF, over the last decade, portfolio investment benchmarked against widely followed emerging market bond indices has grown by a factor of four, to 800 billion USD. The IMF estimates that about 70% of investment in emerging economies is volatile and responds swiftly to changes in market mood and global financial conditions. This investment can play a significant role in external shock transmission.

If the global economy plunges into another recession, capital will leave emerging economies for defensive assets, i.e. developed economies. Emerging markets will face sudden capital stops that usually lead to exchange rate decreases, thereby increasing the debt burden of borrowers and cutting credit, internal demand, and output. This risk is particularly relevant for countries with substantial foreign currency debt.

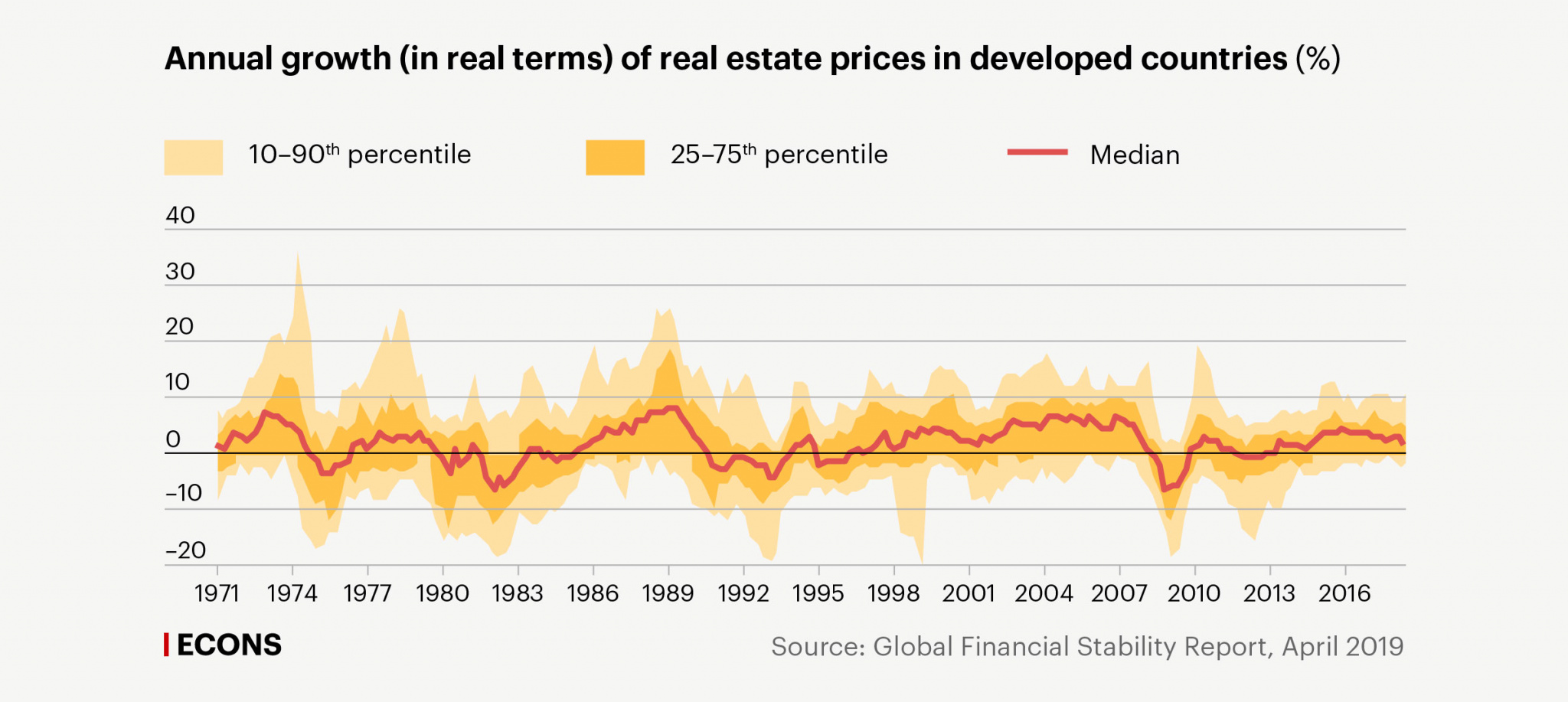

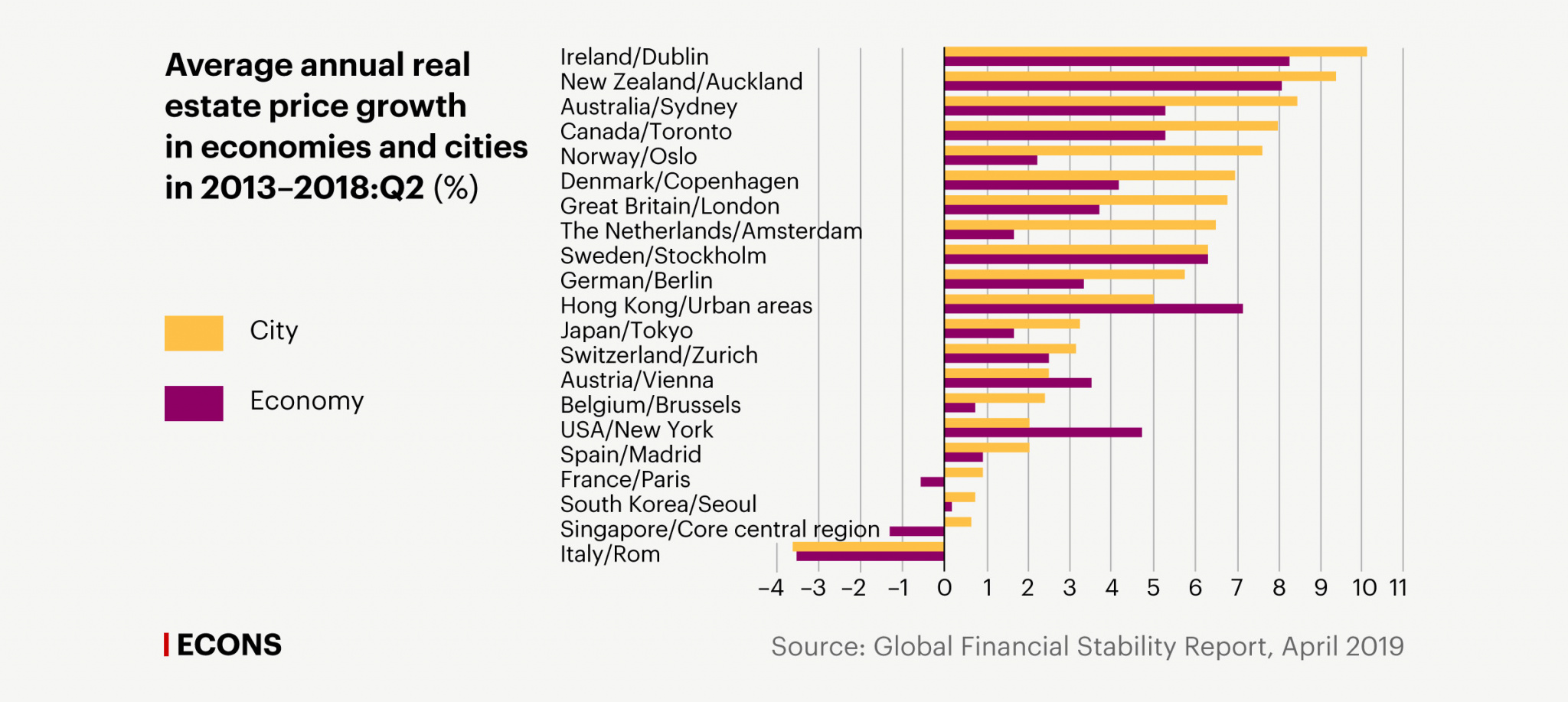

3. Real estate boom

Over the last five years, some countries have experienced growth in real estate prices (for example, housing prices in Hong Kong, Sweden, and Ireland gained on average 5% or more each year from 2013 until 2018), which requires regulators in these countries to take additional measures, primarily in macroprudential policy. Given the increased synchrony in housing price dynamics across countries (see Chart 5), there is a risk of a synchronous fall in real estate prices.

Sharp price adjustments may hinder businesses’ access to funding (commercial property often serves as collateral for corporate loans; housing and commercial property prices correlate) as well as have a negative impact on consumption and generate problems in the banking sector. Housing prices are closely linked with macroeconomic and financial stability. Empirical studies show that recessions aggravated by falls in real estate prices are deeper and longer. As a result, in the event of global recession, countries experiencing a real estate boom are likely to suffer more than other countries.

Chart 4.

Average annual real estate price growth in economies and cities in 2013–2018:Q2 (%)

City

Economy

Ireland/Dublin

New Zealand/Auckland

Australia/Sydney

Canada/Toronto

Norway/Oslo

Denmark/Copenhagen

Great Britain/London

The Netherlands/Amsterdam

Sweden/Stockholm

German/Berlin

Hong Kong/Urban areas

Japan/Tokyo

Switzerland/Zurich

Austria/Vienna

Belgium/Brussels

USA/New York

Spain/Madrid

France/Paris

South Korea/Seoul

Singapore/Core central region

Italy/Rome

–4

–3

–2

–1

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

Source: Global Financial Stability Report, April 2019

City

Economy

Ireland/Dublin

New Zealand/Auckland

Australia/Sydney

Canada/Toronto

Norway/Oslo

Denmark/Copenhagen

Great Britain/London

The Netherlands/Amsterdam

Sweden/Stockholm

German/Berlin

Hong Kong/Urban areas

Japan/Tokyo

Switzerland/Zurich

Austria/Vienna

Belgium/Brussels

USA/New York

Spain/Madrid

France/Paris

South Korea/Seoul

Singapore/Core central region

Italy/Rome

–4

–3

–2

–1

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

Source: Global Financial Stability Report, April 2019

City

Economy

Ireland/Dublin

New Zealand/Auckland

Australia/Sydney

Canada/Toronto

Norway/Oslo

Denmark/Copenhagen

Great Britain/London

The Netherlands/Amsterdam

Sweden/Stockholm

German/Berlin

Hong Kong/Urban areas

Japan/Tokyo

Switzerland/Zurich

Austria/Vienna

Belgium/Brussels

USA/New York

Spain/Madrid

France/Paris

South Korea/Seoul

Singapore/Core central region

Italy/Rome

–4

–2

0

2

4

6

8

10

Source: Global Financial

Stability Report, April 2019

Chart 5.

Annual growth (in real terms) of real estate prices in developed countries (%)

10–90th percentile

25–75th percentile

Median

40

30

20

10

0

–10

–20

1971

1974

1977

1980

1983

1986

1989

1992

1995

1998

2001

2004

2007

2010

2013

2016

Source: Global Financial Stability Report, April 2019

10–90th percentile

25–75th percentile

Median

40

30

20

10

0

–10

–20

1974

1980

1986

1992

1998

2004

2010

2016

Source: Global Financial Stability Report, April 2019

10–90th percentile

25–75th percentile

Median

40

30

20

10

0

–10

–20

1971

1980

1989

1998

2007

2016

Source: Global Financial

Stability Report, April 2019