The cinema hall goes dark, and a roaring lion appears: Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer presents its film ‘Inflation’. An offscreen voice addresses the audience: ‘To understand inflation we must understand money. This is a cow. Come on, prove you are a cow.’ On screen, the oldest currency moos in reply.

In 1933, this short film by MGM was shown in American cinemas before popular films, and became one of the government’s first attempts to make its monetary policy clear to the general public. Today, central banks can learn a lot from analysing the actions of Franklin D. Roosevelt’s administration, which used communication as a weapon against the consequences of the Great Depression, argues Christina Romer, Professor of Economics at the University of California, Berkeley, and former head of the Council of Economic Advisers for Barack Obama’s Executive Office.

From esotericism to openness and discoveries

‘Since I’ve become a central banker, I’ve learned to mumble with great incoherence. If I seem unduly clear to you, you must have misunderstood what I said.’ These legendary words were spoken by Alan Greenspan, Chair of the Fed, about thirty years ago and are often quoted in the epigraphs of papers on central banks’ communication policies (for example, here and here). In the 1980s, central banking was compared to an esoteric art due to its extreme complexity, but by the early 2000s central banks’ communication policies had undergone a radical change.

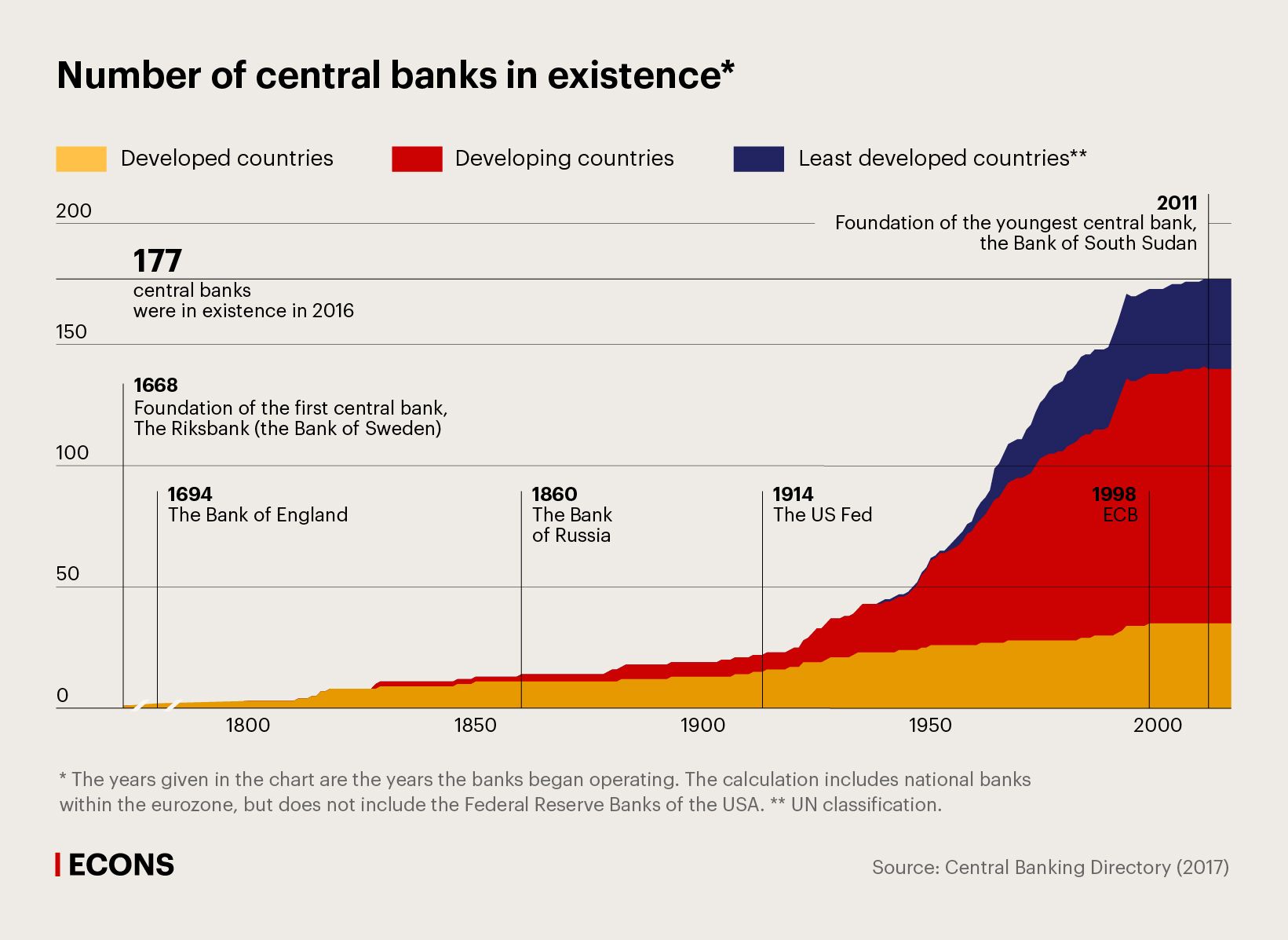

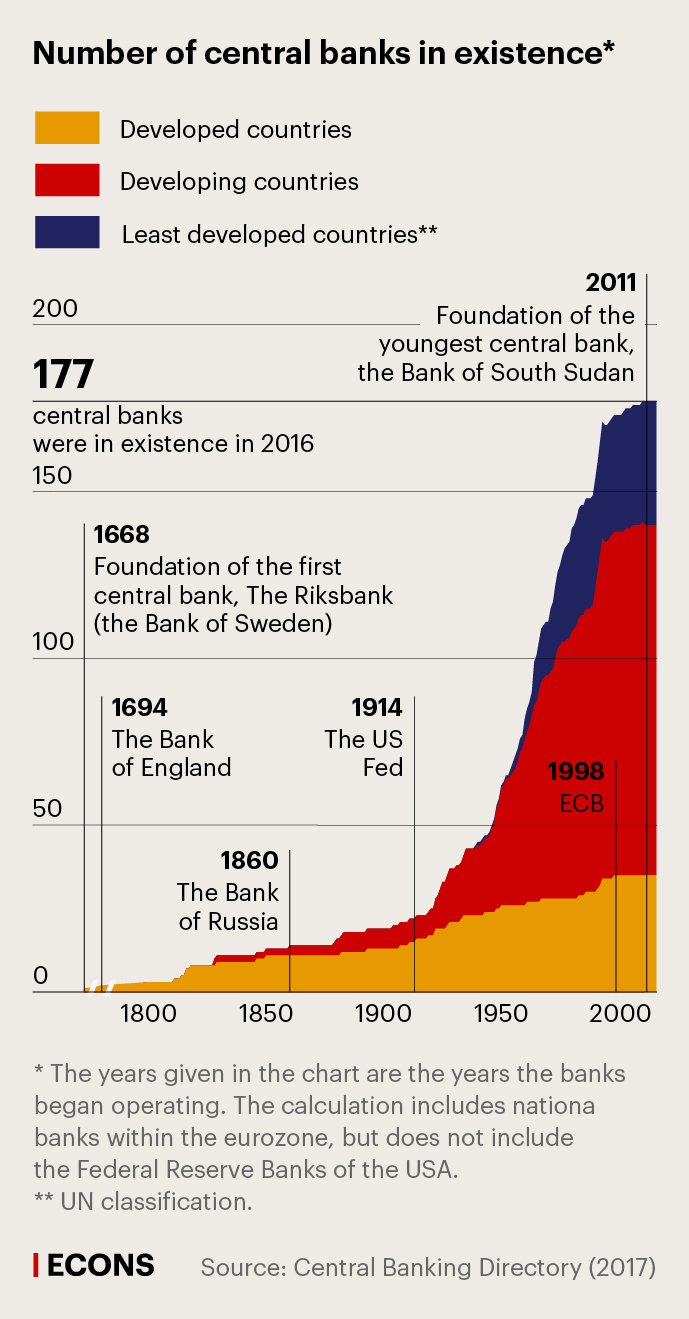

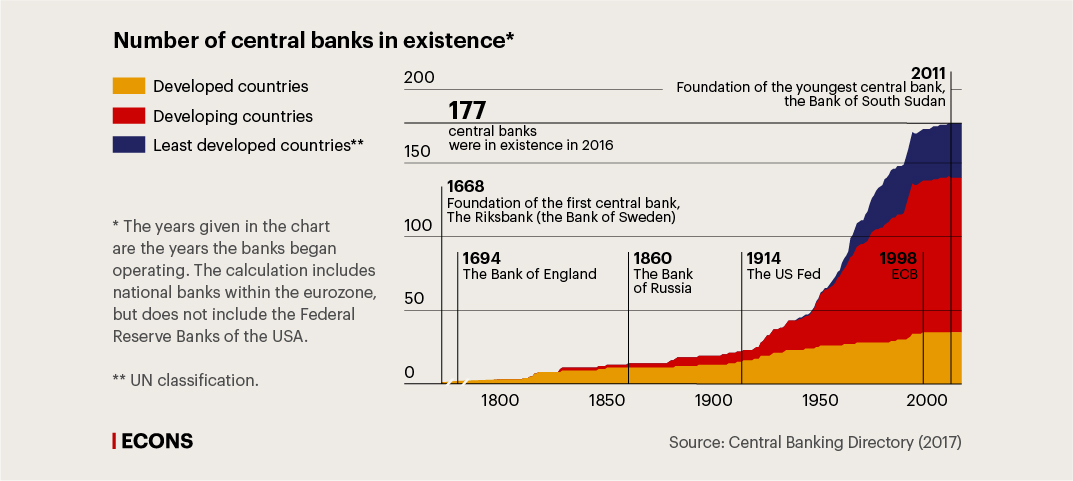

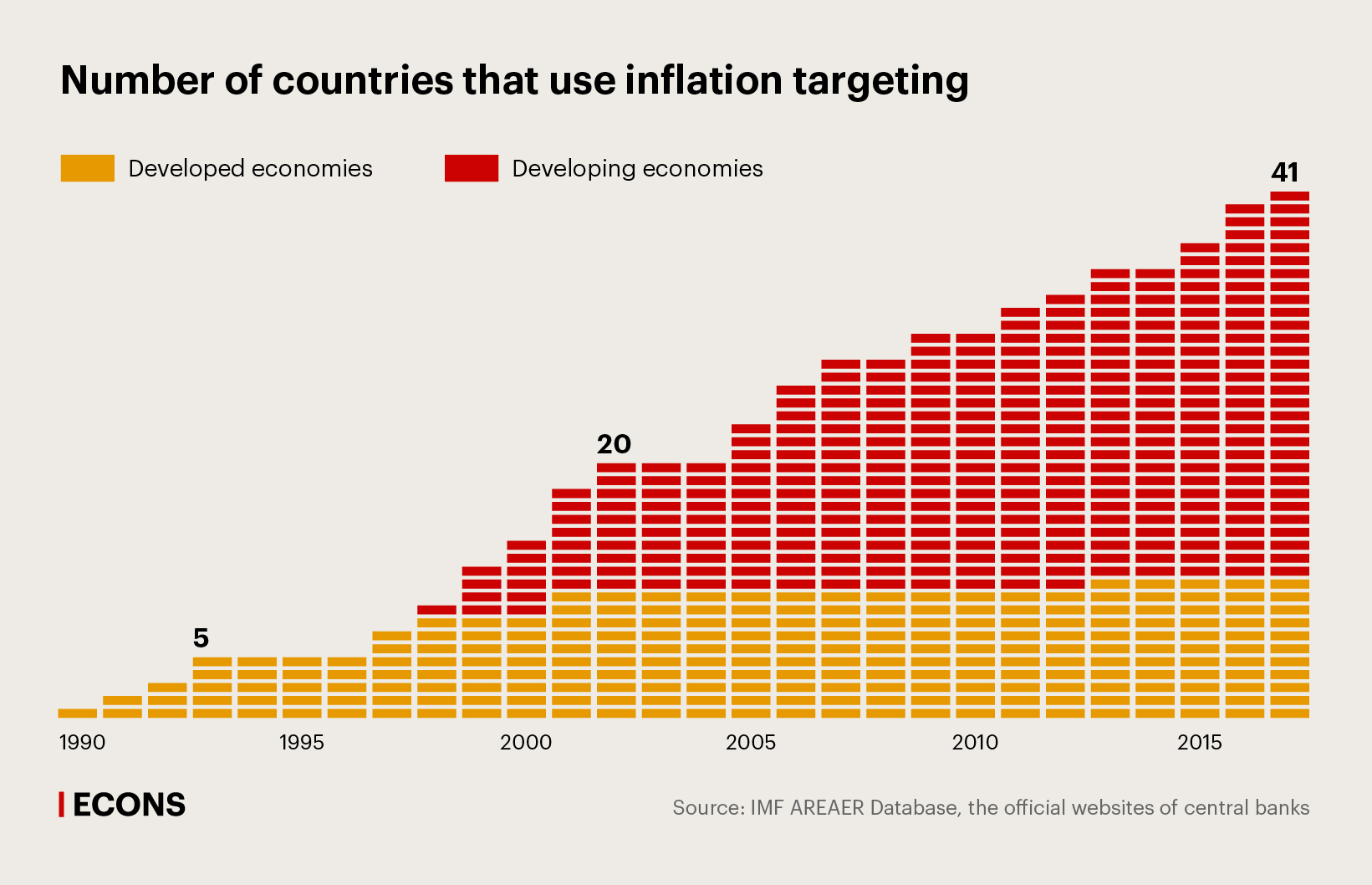

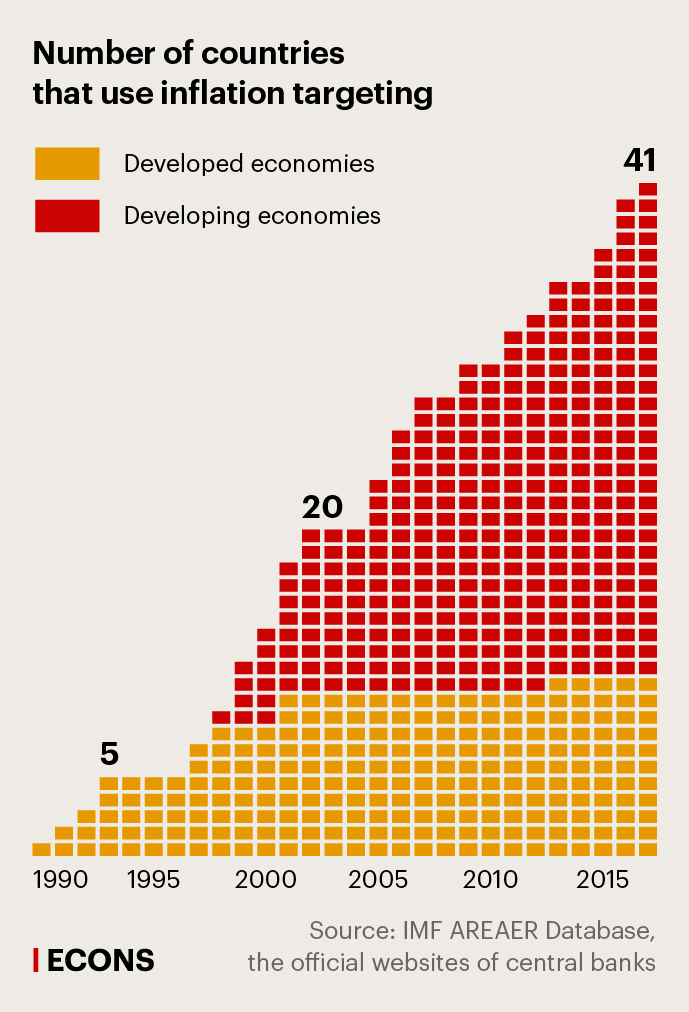

The shift towards inflation targeting that started in the last decade of the 21st century required central banks to be more independent. This independence, in its turn, required central banks to be more accountable and transparent. Open communication has become a way to legitimise central banks’ autonomy in policy-making, and is now our most important tool in managing inflation expectations.

Central banks broaden their audiences

Central banks initially focused on the financial markets, i.e. the professional audience; only ten years ago did they begin paying attention to mass audiences. It was then that central banks realised how little interest people had in their work.

In her article, published by the Journal of Macroeconomics, Carola Binder, an economist at Haverford College, analysed the results of surveys carried out by central banks in different countries to establish people’s attitudes towards the banks’ work. It turned out that many had no attitude at all. A 2005 survey showed that 68% of Japanese knew next to nothing about the Bank of Japan and its work; according to a 2011 survey, 45% of South Africans had never heard of the South African Reserve Bank; and a 2016 survey demonstrated that the existence of the European Central Bank was news to every sixth adult European.

Lena Dräger, Michael J. Lamla, and Damjan Pfajfar, whose article on the role of central bank communication in improving the efficacy of monetary policy was published in the Fed’s Discussion Series, believe that the majority of people choose rational inattention. People do not keep track of monetary policy because they cannot see any apparent personal gains from doing so, while the costs of processing excessive amounts of information are high – especially since central banks’ information is extremely difficult to understand. For example, only 2% of adult Americans can understand the minutes of the Federal Open Market Committee, fewer than 10% of Americans can comprehend the Fed’s Beige Book summaries, and even discussions of monetary policy in the mainstream US press are accessible only to around 20%. At the same time, speeches by President Trump are comprehensible to 70% of Americans, and Elvis Presley’s songs reach 60%. This comparison was drawn by Andy Haldane, Chief Economist at the Bank of England, at a conference at the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco. Howard Davies, former Deputy Governor of the Bank of England, argues that this situation is common: ‘There are no comparable statistics or verdicts for the ECB, but I would be surprised if the results were any different.’

Translating from central bankerese

A language barrier is preventing people from acquiring first-hand information from central banks, as the Flesch–Kincaid readability test demonstrates when applied to press releases and reports published by central banks. This test shows how difficult a text is in terms of the lowest level of education needed to understand it. The results of the test depend on the number and length of the words in the text. The Bank of England and the Bank of Scotland publish the easiest announcements: to read them, you need to have successfully finished school (equivalent to 12 years of education). On average, to comprehend the texts released by the central banks of developed countries, you need at least 16 years of education (equivalent to a college degree in the US). To understand the Fed’s announcements, even a college degree is not enough: Americans need 18–19 years of education for that.Communication via the mass media, who act as translators from ‘central bankerese’, might be similarly ineffective, according to an experiment held in the USA. The researchers wanted to discover how various forms of communication influence people’s expectations about inflation. First, the respondents gave their inflation forecasts; then the researchers split the participants into groups and provided each group with the official forecast in one of several ways, including giving them a newspaper article or an official press release, or telling them the Fed’s inflation target. Next, the respondents were asked about their inflation expectations once again. A news article from USA Today proved to be the least effective: participants who read it later reduced their inflation forecast by 0.5 percentage points (or around one-fifth), in comparison with 1–1.1 percentage points in other groups. Given that the article contained the same figure as the press release and oral announcements, the authors conclude that people discount information provided by the media. Mr Haldane pointed out that the decreasing credibility of mass media is a pressing issue when it comes to its use as a communication channel; for example, only one-third of Americans trust the media.

Analysing the results of the experiment, the researchers came up with one key recommendation: not to rely on the media, and to address general audiences directly. However, they did not venture an explanation of what they meant by ‘addressing the general audience directly’, simply calling for ‘new approaches’. The number of existing studies on central bank communication is insufficient as a scientific basis for decision-making. That said, academia is paying more and more attention to central bank communication: in 2000, ‘central bank communication’ appeared in only 15 scientific works indexed by Google Scholar, while in 2018, it was found in 389 papers, or just over 1% of all the studies on central banking written that year.

New approaches

Meanwhile, central banks themselves are on the hunt for new approaches. For example, in November 2017, the Bank of England started publishing visual summaries of its quarterly inflation reports. These summaries are written in accessible language and contain pictures and definitions of all technical terms. The Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level of the simplified report version is equivalent to eighth-grade level, say Mr Haldane and Michael McMahon, Professor of Economics at Oxford University. The authors point out that these simplified reports have proven useful for professionals as well: 70% of the respondents who took part in the Bank of England’s business survey admitted that Bank’s policy had become clearer, and 60% of the respondents said their confidence in the Bank had improved.

As Chief Economist at the Bank of England, Mr Haldane also seeks to explain the Bank’s policy himself, without any intermediaries. Since the middle of 2017, he has been regularly touring the UK to meet with local entrepreneurs, activists and anybody with questions to ask him, as well as to learn about the real state of local economic affairs. ‘You cannot do that sat in London all the time, poring over the numbers in your spreadsheet,’ explained Mr Haldane.

Central banks not only convey information in a simple form in their attempts to make it accessible to the public, but also seek to make the audience itself more financially literate.

Central banks in dozens of countries around the world implement financial literacy programmes themselves or take part in similar national government programmes. For example, the Bank of Ireland runs a financial literacy programme for children

aged 7 and older, while the Bank of Uganda offers programmes for

various target groups, from schoolchildren to business associations. To cultivate people’s financial awareness, the Bank of Russia created the website fincult.info, which has a special section for schoolteachers and financial education activists. The better citizens understand economics, the more informed decisions they make. In order for a central bank to attain its goals, it is essential that citizens, regardless of their position in society, understand the economic and financial conditions that influence their lives, points out the Central Bank of Brazil.

Likes for central banks

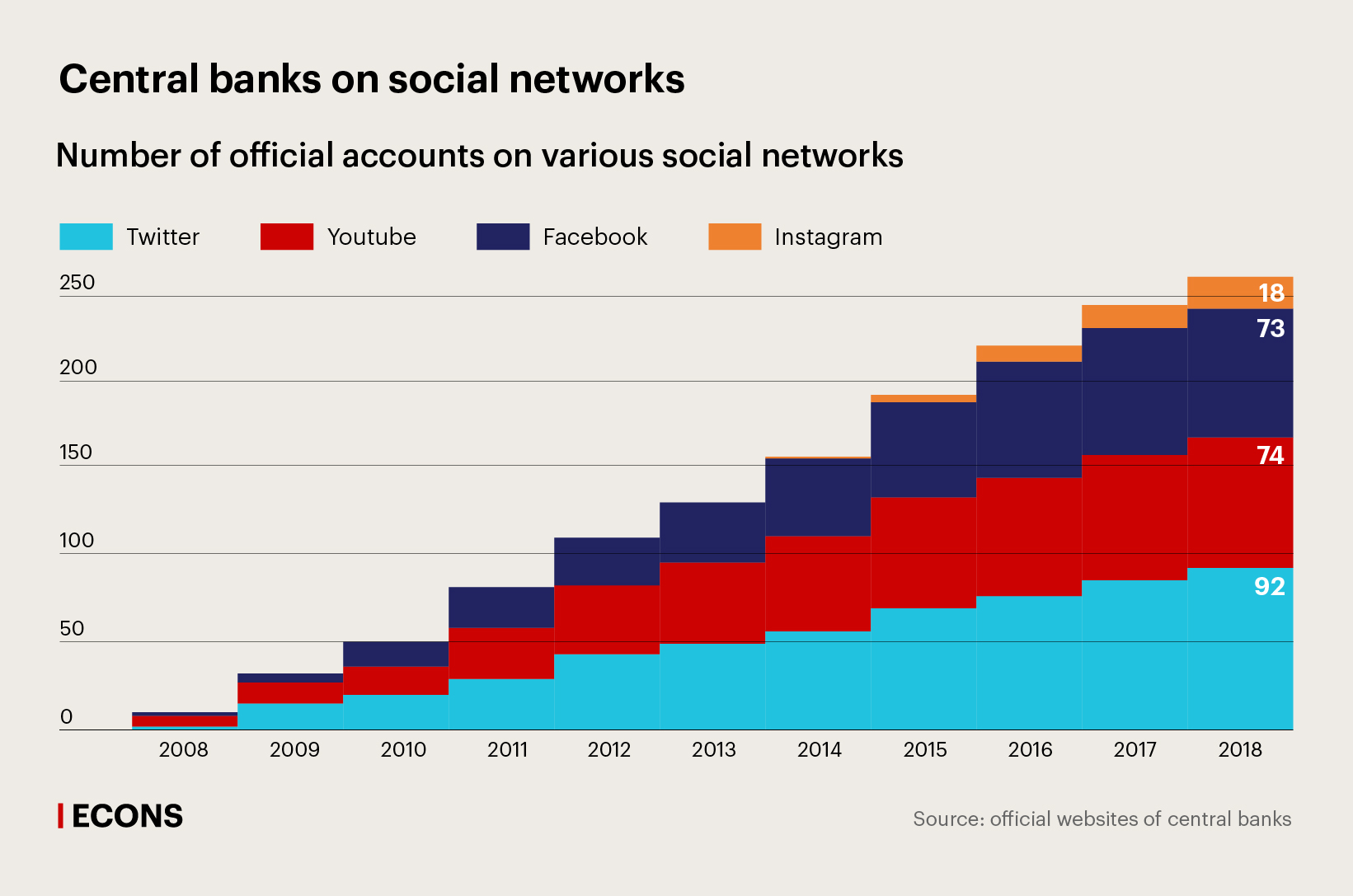

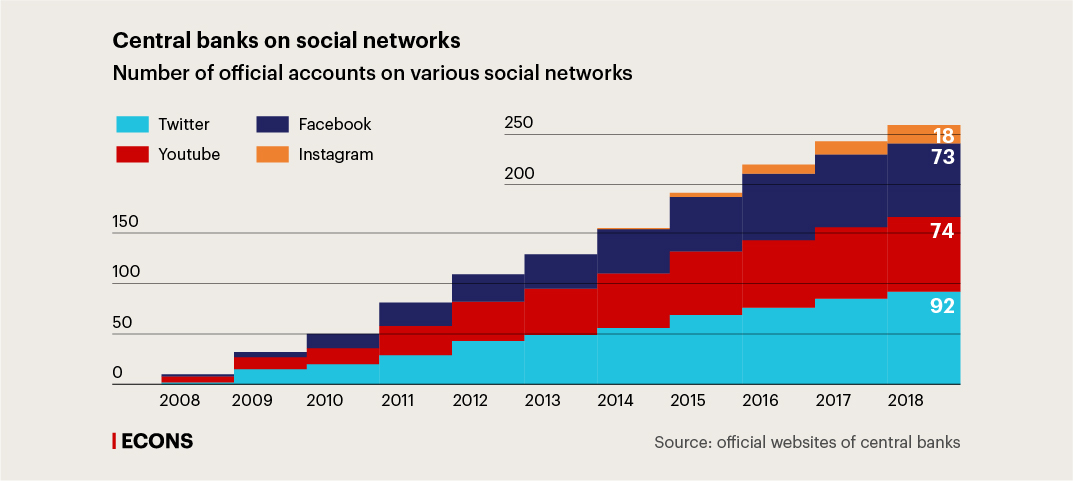

In her survey article on central bank communication, Ms Binder argues that social networks, blogs, and messenger apps can help central banks reach mass audiences without engaging intermediaries. However, this issue is largely unresearched. In the past decade, central banks around the world have been turning to social networks in droves (see the chart), and are still striving to expand their presence there: for example, since 2015, they have created scores of Instagram accounts.

However, more detailed analysis shows that even leading central banks are still relative newcomers to social networks. For example, President Trump’s Twitter account, where he regularly makes big announcements that can instantly crash the markets, has more than 59 million followers (as of March 2019), while the official account of the Fed, the decisions of which influence the whole global economy, has a little over 500,000 followers, as its content largely consists of links to the Fed’s official statements.

To use social networks more effectively and attract an audience, central banks have to motivate their employees to be active on social networks. For example, in 2014, the Board of Directors of the Bank of Finland set special KPIs that included a certain number of posts to be published on the Bank of Finland’s blog in a year, or, for a department, a certain number of employees who would tweet about the Bank’s work and gain at least 300 followers. The results of these KPIs are published in the Annual Report.

Central banks are looking into new ways to communicate with the public and unconventional ways of presenting information, such as cartoons, videos, and interactive games. For example, the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco invites everyone to ‘Chair the Fed’ (the name of an online game where everyone can manage the interest rate to ensure full employment and an inflation rate of 2%). The goal of the Bank of Russia’s interactive game ‘The Mystery of the Lost Piggybank’ is to foster financial planning skills.

At the end of last year, the Bank of Jamaica hit the headlines for its series of videos featuring reggae singers and dancers talking about inflation and inflation targeting. On Valentine’s Day, the Bank of Jamaica posted some flowery phrases on its Twitter account, that economists might use to declare their love (‘Before you, my life was like an economy in stagflation!’; ‘My demand for you is inelastic, and you raise my interest rate like no other!’). It also reminded readers that Alan Greenspan had to propose to his wife, Andrea Mitchell, three times before she figured out what he was asking. Those days are gone: according to Mr Greenspan’s successor, Ben Bernanke, monetary policy is 98% talk and 2% action.