The supply of stable and affordable electricity has been traditionally of a higher priority in Russia than environmental targets, and its vast hydrocarbon reserves make domestic gas-fired power generation a stable, low-cost business. However, pressure from global environmental-protection initiatives is mounting.

The carbon border adjustment (CBAM), set to take effect from 2023, is part of Europe's Green Deal initiative that will impose new taxes on imports linked to high-emission production. Although details of the mechanism are not yet final, CBAM could hurt Russian exporters' cost competitiveness.

The European Union is Russia's biggest trading partner, accounting for 37.5% of the country's goods exports in 2020. Russia's main export-oriented industrial sectors, including oil and gas, metals and mining, chemicals, and fertilizers, rely heavily on electricity. Platts Analytics estimates that Russia's power producers generate more CO2 than those in Western Europe or the U.S., at 0.50 tonnes of CO2 per kilowatt hour (t/kWh) of electricity delivered, versus 0.20 t/kWh and 0.37 t/kWh respectively; that's only slightly higher than the global average of 0.48 t/kWh.

Russia ratified the Paris Agreement on climate change in September 2019 and submitted an updated Nationally Determined Contribution in late 2020 that requires emissions to be 70% below 1990 levels by 2030 (including land-use changes). There has been a massive push for initiatives within Russia to improve climate disclosure amid increasing calls for greener energy from end users and investors. New legislation to move things along is underway, including the law on carbon certificates passed by the State Duma in June 2021, and regional decarbonization pilots in Sakhalin and other regions. Still, it remains to be seen how much progress can be achieved before CBAM goes into force in two years' time.

European fees

Currently, there's no domestic carbon price mechanism in Russia. However, CO2 emissions from electricity generation will be increasingly important for the country's industrial users, especially exporters, listed companies, and those with environmental goals. The mining and industry sectors consume as much as 58% of the energy produced, and households only 16%.

The EU plans to release details of CBAM in July 2021 and implement it two years later. Russian exporters can manage the financial impact over the next several years. Still, in the longer term, the carbon intensity of electricity purchased may become key for competitiveness as the emissions gap between Russia and the EU widens. According to BCG, CBAM could cost Russian exporters €3-4,8 billion per year in tariffs. Since then, the EU Emissions Trading System (ETS) carbon price has increased, surpassing €50 per metric ton in May 2021 compared with about €30 per metric ton in mid-2020, while the list of in-scope industries has become longer since.

Details of CBAM has not been clarified yet. For Russian exporters and their electricity suppliers critical areas of CBAM to be clarified include reporting and verification standards (for instance the scope, market versus location method, and acceptability of various types of carbon offsets), as well as the list of industries included at various CBAM stages, not to mention the eventual price of EU carbon units.

Russian footprint

The November 2020 presidential decree (link in Russian) that set an emissions-reduction target of 70% compared with the 1990 level (when adjusted for land use and forestry) also allows for emissions to increase to foster economic growth. And although the president stated recently that Russia's net accumulated emissions over the next 30 years should be below the EU's, no specific target or strategy to achieve this has been announced.

However, Russia already generates less carbon dioxide (CO2) than the EU, at about 1.7 billion tons annually versus about 2.9 billion tons for the EU in 2019. This implies it may not need to reach net zero by 2050 to achieve its goal, and may keep emissions stable depending on the EU's decarbonization path and the methodology for calculating net GHG emissions. For example, theoretically, taking atmospheric lifetime and land-use changes into account, Russia could potentially meet its long-term target - without any substantive change to emissions from combustion - should the EU's 2050 emissions decline to only 50% of current levels.

At the same time, the performance of the European countries has been consistently declining in recent decades. Accelerated decarbonization as the EU delivers on its net-zero pledges would require corresponding reductions in Russia.

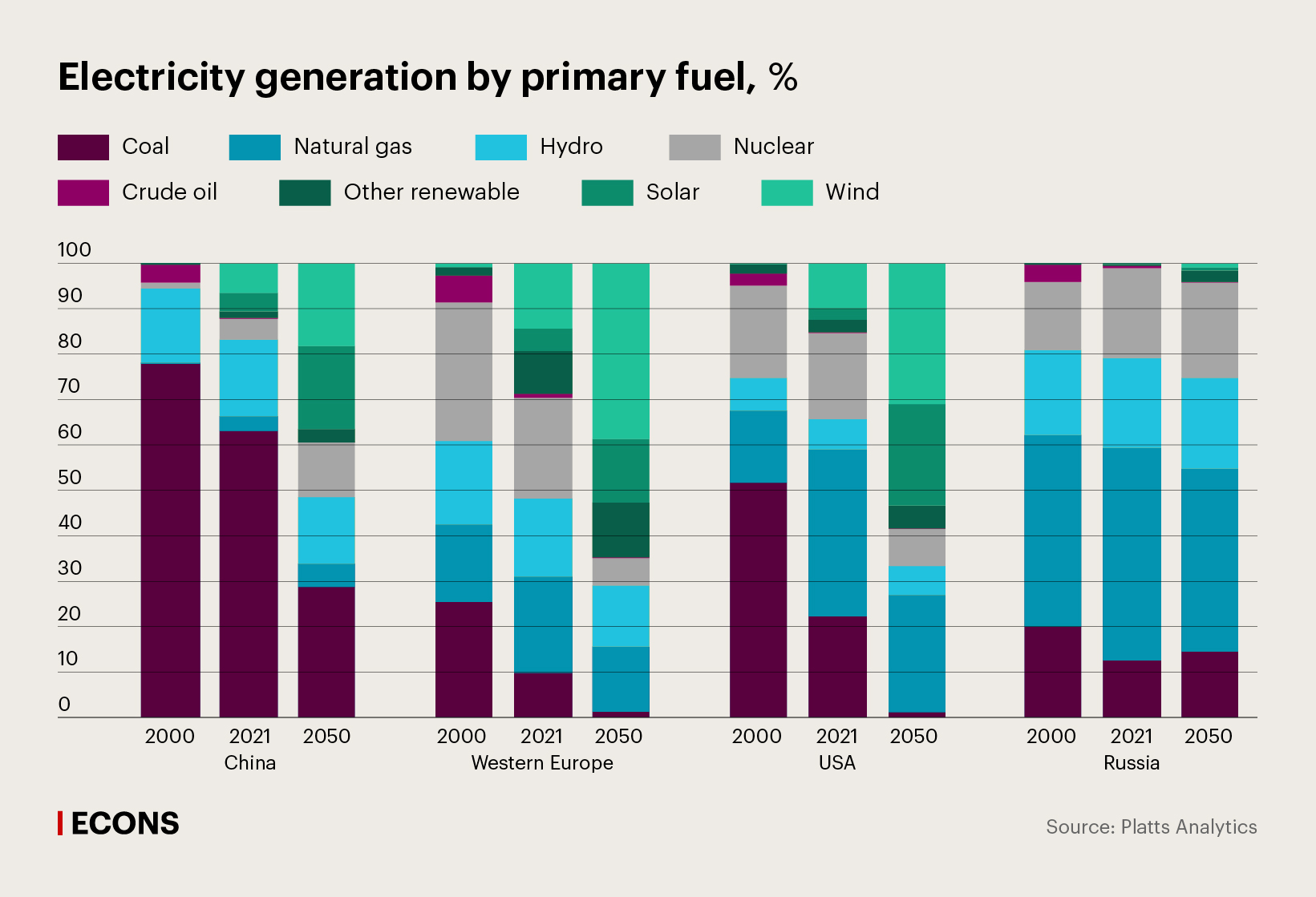

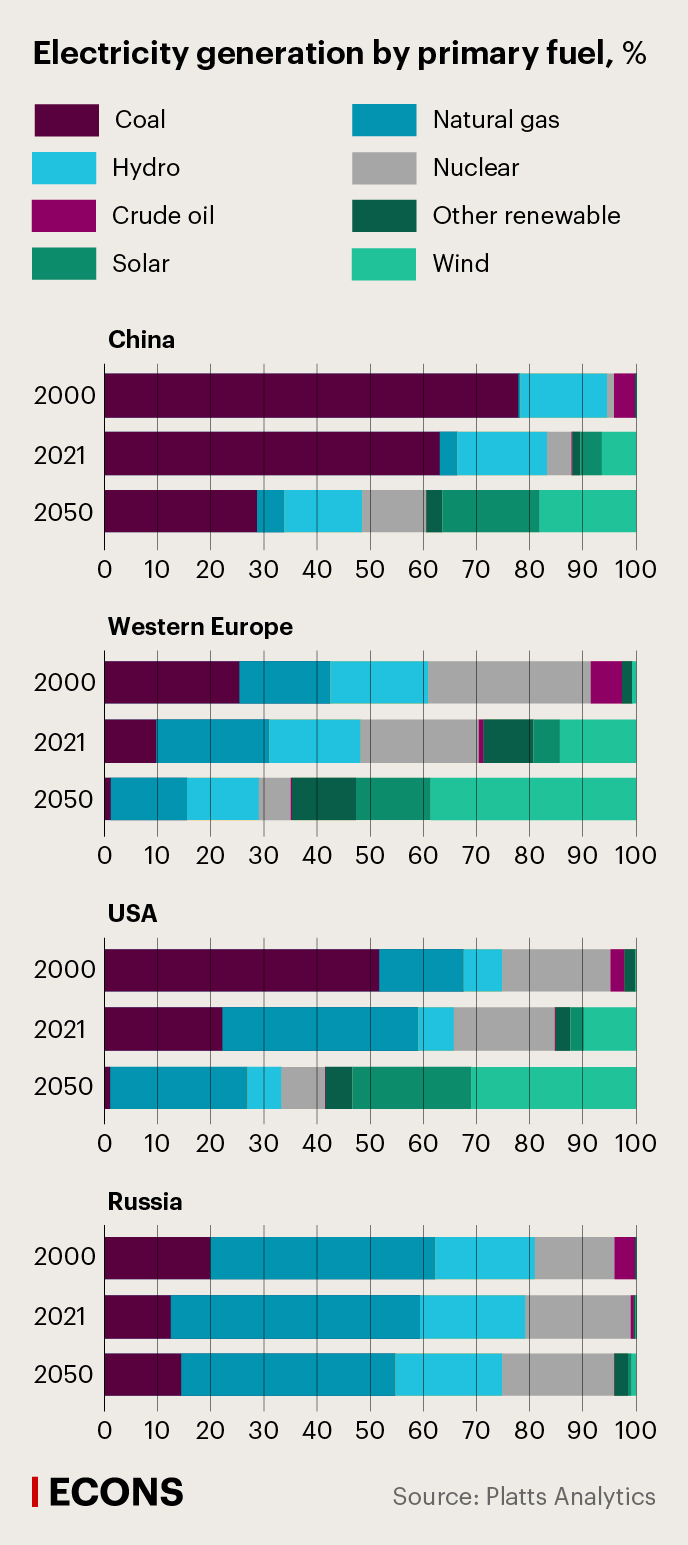

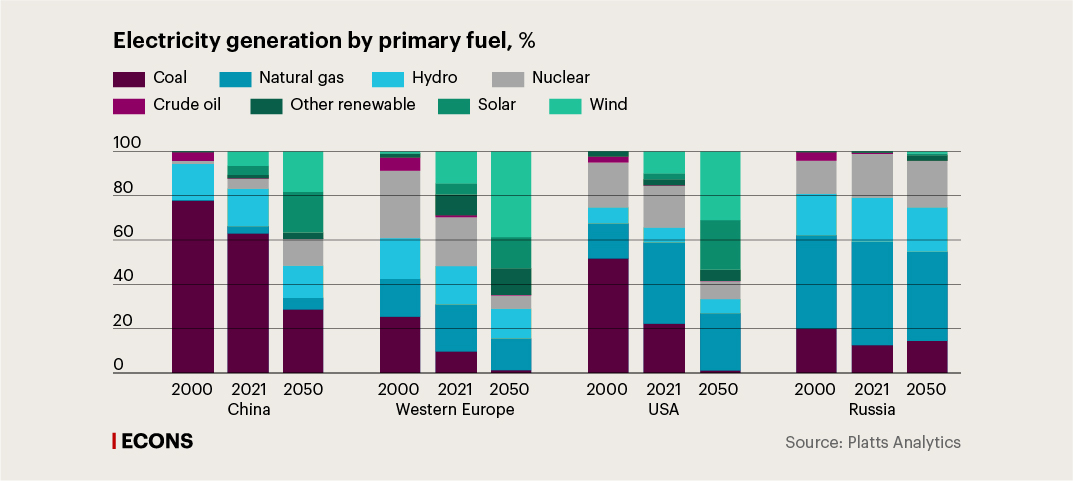

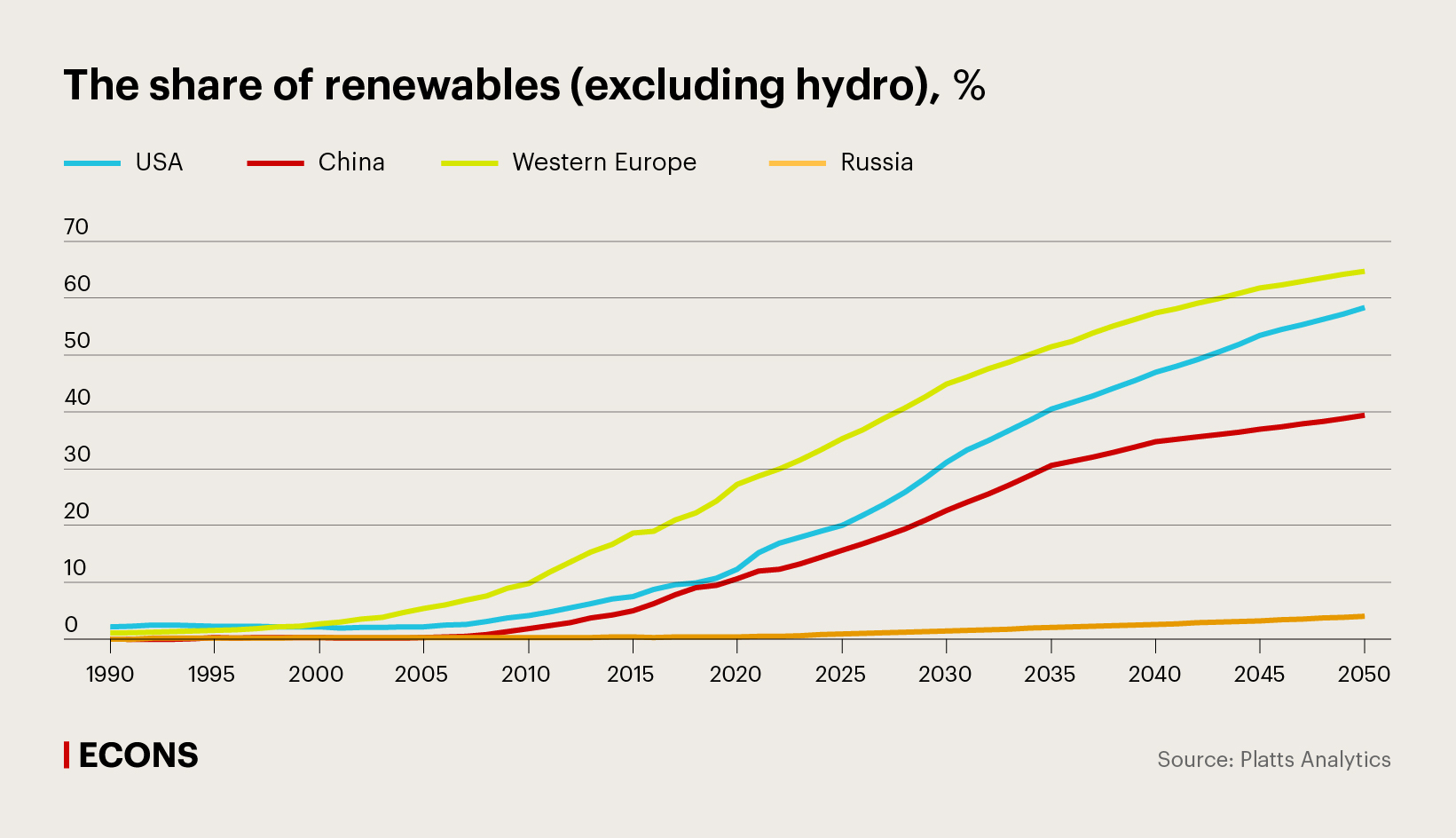

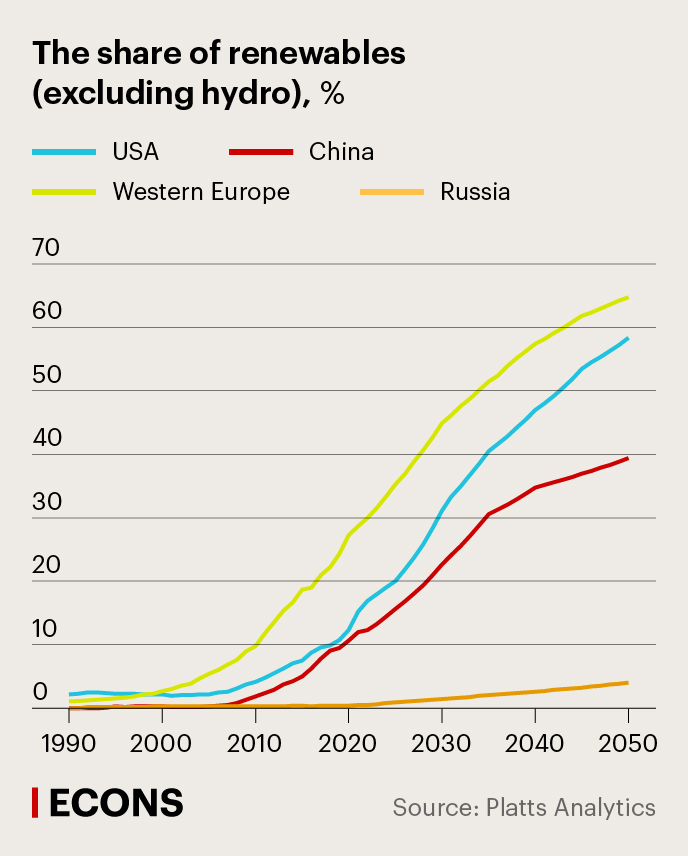

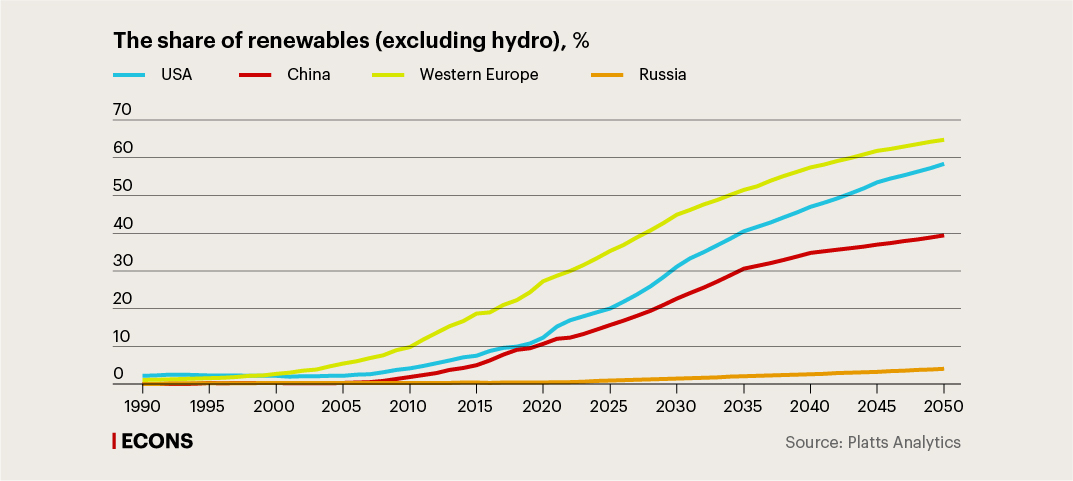

According to Platts Analytics, through 2050, the emissions gap between Russia and the rest of the world is likely to widen. In Russia the share of renewables in the energy mix remains to be much lower than in many other markets. In 2020 the capacity of solar and wind generation represented only 0.3% of generation volumes.

Gasification helps boost regional economic development and utilizes the country's vast gas reserves, but has little impact on domestic gas demand. The Russian government sees the broader gasification of the economy as a cost-effective means to reduce reliance on diesel and oil-based power, especially in the industrial sector. The government is pushing Gazprom to build out its domestic transmission and distribution network to isolated regions, which has been the greatest driver of gasification in the country, particularly within the framework of the government's Far East Development Strategy.

The average gasification rate in Russia have increased from 50% to 70% over the past two decades, at the same time, only about 62% of the rural population has access to natural gas for heating.

94% of electricity demand in Russia stems from two end-use sectors: industry (including energy generation) and buildings (residential and commercial). Electricity demand for buildings and industrial activity could increase by 26% by 2050. Total electricity demand will increase by around 0.7% per annum on average. Such modest growth could foster investment in oil-and-gas alternatives, since new capacity can replace older fossil-based generation assets. We project that non-fossil sources (renewables, hydro, and nuclear) will capture 64% of incremental load growth. Yet we believe coal- and gas-fired power will continue to increase on an absolute level.

In order to decrease the volume of heat generation, it would be necessary to simultaneously increase the input of renewable energy sources and significantly postpone the decommissioning of old nuclear power plants, which is unlikely: most of them were built in the 1970s and require decommissioning in the very near future. For thermal generation to decline, Russia would need to both expand renewables and delay the phase out of older nuclear assets, which appear far off: much of the assets dates back to the 1970s and faces imminent retirement.

Green future

Despite having a more carbon-intensive power industry than in many European countries, about 40% of Russia's electricity came from low-carbon nuclear and hydropower production in 2020. On paper, this proportion of non-fossil energy should cover the needs of the country's largest exporters and other energy consumers that face environmental reporting requirements or have emission-reduction targets.

In June 2021, the Russian parliament approved draft legislation (link in Russian) on decarbonization, green certificates, and climate projects. It requires large companies to report emissions, and introduces the concepts of climate projects and trading in carbon units. Still, Russia's 2020 energy strategy is focused on reducing emissions by increasing efficiency, for example through better fuel utilization, lower grid losses, and energy-efficient buildings--rather than via renewables.

In addition, the Ministry for Economic Development and state-owned development corporation VEB have submitted proposals for Russia's own green taxonomy. The government has also approved a roadmap to make Sakhalin the first region to achieve net-zero-emission status by 2025. The roadmap requires a regional CO2 trading system to start functioning in September 2021-July 2022 and to be synchronized with appropriate international systems. Other regions, such as Kaliningrad, are also looking into pilot decarbonization programs.

Environmental reporting is evolving in the EU and in Russia but not necessarily in parallel, so regulatory harmonization is paramount for Russian companies. In its March 2021 resolution to adopt CBAM, the European Parliament stressed that foreign companies should have the option to prove in accordance with EU standards for monitoring, reporting and verification - that the carbon content of their product is lower than EU levels. This would not only reduce the amount foreign companies have to pay, but also create an incentive for innovation and investment in sustainable technologies.

Even if Russian-issued certificates are not accepted internationally, Russian producers of non-carbon electricity might attempt to obtain international certificates. EN+, for instance, obtained I-REC in late 2020 for its solar generation operations, and TGC-1 did so in 2021.

More fundamentally, although green certificates or power purchase agreements (PPAs) for nuclear and hydropower can help improve reporting, they do not change Russia's underlying fuel mix and overall emissions. Consequently, they do not correspond to the stated ultimate goals of the EU's green policy and CBAM. Rather, they allocate existing low-carbon electricity to emission-sensitive customers (such as exporters, or companies with emission-reduction commitments), while high-carbon electricity goes to customers that do not need to report their carbon footprint.

Cautious state support

Compared with the EU’s massive renewables support packages, the Russian government’s support for the sector appears cautious. Renewables enjoy special CSAs, similar in principle to those used for construction and modernization of traditional thermal, hydro, and nuclear assets (when supplier undertakes obligations for construction and commissioning of an entity in exchange of guaranteed reimbursement of costs through the increased cost of capacity – Econs’s note). This is quite unusual given the inherent intermittency of renewables generation, and contrasts with feed-in tariffs or subsidies common in the EU

The average cost of wind and solar generation is a lot higher in Russia than for traditional gas-fired generation and energy producers in many other countries. The main reason is the low domestic gas price. However, another key factor is that Russia's most densely populated regions (such as Moscow, St. Petersburg, and environs) lack solar and wind resources. Russia's windiest areas, near the Arctic coast, are scarcely populated and generation equipment needs to be suitable for the area's terrain (lack of transport infrastructure) and harsh weather conditions (such as snow and frost). Renewables growth stems mainly from southern regions with more suitable climates and sufficient electricity demand, such as Orenburg, Stavropol, Rostov, Astrakhan, and Samara.

In 2020, some new bids for wind projects were well below certain new nuclear and coal-fired projects: at about RUB65,000 per kWh, for example (see chart 17). This follows the successful start of equipment manufacturing by international and local players. Vestas started producing wind turbines in Ulianovsk with Rusnano (supplied Fortum's projects), Siemens opened a wind turbine manufacturing facility in Leningrad Oblast (Enel's Azov and Kolsky wind projects), Rosatom is developing its wind turbine production, and Hevel is producing solar modules in Novocheboksarsk, Chuvashia (over 300 kW of solar capacity annually). The availability of local equipment is important because of strict component requirements to qualify for the government's renewables support scheme.

Corporate demand

Beyond regulations, we believe large industrial companies, especially exporters and those with climate commitments, could spur renewables development. Many Russian corporates, as well as international companies operating in Russia, are voluntarily setting emission-reduction targets amid mounting environmental pressure from investors and contractors along the value chain.

On the one hand, some large Russian companies intend to restructure their asset portfolios based on carbon intensity to reduce emissions reported by export-focused assets. For example, steelmaker Evraz plans to sell its coal-mining assets, and aluminum producer Rusal is considering a spin-off of its high-emission mining, alumina, and aluminum production assets. Rusal, to be renamed AL+ if the spin-off proceeds, will focus on exports and the new company on developing the domestic market. Carbon-led corporate restructurings are not unique to Russia and happen in other countries too. Although asset reshuffling cannot bring down emissions, it illustrates that companies are becoming increasingly sensitive to their reported carbon footprint.

On the other hand, surcharges, capacity payments, and cross-subsidization of residential sector will push up industrial users' electricity bills. This could make inhouse power production a viable option for them, as well as a direct way to reduce emissions that's not as dependent on regulatory developments. For example, Russian oil company Gazpromneft uses solar panels on its refinery in Omsk, a city that enjoys 308 sunny days per year on average. Lukoil uses renewable energy in its Bulgarian and Romanian operations and has been investing in solar panels at its oil refineries in Samara and Volgograd.

Small and midsize enterprises in the south of Russia are increasingly looking at rooftop panels as a way to reduce their electricity bills, especially after the law on microgeneration was adopted. For isolated energy systems in scarcely populated areas with poor logistics (such as the Arctic and Far Eastern districts), a distributed energy system based on renewables and backed with thermal generation could be cheaper than transmission grids. Some of those areas have relatively favorable solar and wind conditions (Arctic seashore, Primorsky, Khabarovsky Krai, and Buryatia), although wind and solar equipment would need to be customized for harsh weather conditions, which could make them more expensive, and need to be supplied to areas where transport infrastructure is limited. Moreover, there are no clear economic incentives for private players to invest in renewables as long as the government continues to subsidize the cost of fuel supplies in certain remote areas (so called Northern Supply).

Hydrogen may offer interesting growth opportunities for Russian renewables in the future. For example, Enel is considering producing hydrogen at its Kolsky wind unit (currently under construction) for export to neighboring Nordic countries. Russia's nuclear power producer Rosatom and its subsidiary AtomEnergoProm both have significant potential to produce so-called yellow hydrogen. In April 2021, EDF and Rosatom agreed to collaborate on promoting CO2-neutral hydrogen in Russia and Europe, which might create a platform for technological advancement in the future. Rosatom has an agreement with the Sakhalin region's government to develop a facility complex for the Asia-Pacific market. Still, these plans are at a nascent stage, as is the global hydrogen market, with little certainty about demand or supply demand.