‘Don’t Get Me Wrong’: the Central Bank’s Language

Over the past three decades central banks have moved away from ‘ esoteric art’, ‘incoherent mumbling’, and ‘never explain, never excuse’ (this last aphorism belongs to the governor of the Bank of England from 1920 to 1944, Montagu Norman) and moved on to explaining its decisions in detail and being as transparent as possible.

Today, when the vast majority of central banks have social media accounts, it is hard to believe that the first spokesman for the Bank of England, when hired in the 1940s, was instructed to ‘keep the bank off the press and the press out of the bank’. In part for this attitude to communication, central bankers were often challenged ‘to leave their ivory towers’.

So what’s changed? Central banks began to transition to inflation targeting. Compared to previous paradigms of money management or the gold standard, this regime was like magic – now central banks sought to manage the expectations and sentiments of the economic agents who make decisions about whether to spend or to save. It is the balance of these sentiments in a market economy that has an impact on inflation from the demand side. There are two ways to influence people's behavior – through interest rates and through communication. Moreover, even purely instrumental decisions on the interest rate should be presented in such a way that people trust the central bank and begin to behave accordingly. The art of communication has thus become an essential skill for the modern central banker.

Naturally, the question arises - what kind of central bank communication can be regarded as high quality? In literature, as a rule, two parameters are highlighted. The first is readability. This criterion answers the question of what level of education is needed to understand central bank texts. Knowing the level of readability, we can say what potential audience the regulator can reach at the current level of comprehensibility of its communications -- will only highly qualified academics understand them, or will they be able to speak directly to the widest audience? The second criterion is transparency. This answers the question of how much detail the central bank provides about its policy.

More complicated than quantum mechanics

As Jonathan Fullwood of the Bank of England pointed out in the bank's unofficial blog Bank Underground, today's central bank communications are unjustifiably complicated. By his calculations, the reading grade level of most mass media articles and fiction written by the greatest writers is no more than ten. Even Nobel Prize winner Richard Feynman’s lecture in physics that introduces Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle has a reading grade level of less than eight. However, central bank communications require a reading level of grade 14!

These scores are made using the classic Flesch−Kincaid Grade Level scale (used, among other things, in Microsoft Office's readability scores). It calculates the complexity of a text based on two simple parameters the average word length in syllables and the average sentence length in words. Developed about half a century ago, these readability formulae are still very popular today. Among other things they are used by researchers into the quality of central bank communications and by the central banks themselves, for example when preparing speeches for management.

David-Jan Jansen of the Central Bank of the Netherlands in 2010, using the Flesch Kincaid Grade Level scale, demonstrated the existence of an inverse relationship between the clarity of central bank communication and the volatility of financial markets. In 2013, Ales Bulir of the IMF and coauthors, using the same scale, concluded that the low readability of central bank materials is associated with the increased volatility of inflation.

A little later, in 2014, economists at the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis analyzed the statements of the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) of the US Federal Reserve using the Flesch-Kincaid test. It was found that as the FOMC statements became more detailed, they also became less comprehensible. By the end of Alan Greenspan's presidency in January 2006, the FOMC statements consisted of an average of 210 words and required a reading level of grade 14. In subsequent years, amid the global financial crisis, the size and complexity of the texts increased dramatically -- during Ben Bernanke's chairmanship, by January 2009 the statements had reached an average of 400 words, and under Janet Yellen (who chaired the Fed from 2014 to 2018) exceeded an average of 800, and they required a reading level of grade 16 and grades 18-19, respectively. Thus, the FOMC's statements have become incomprehensible even to college graduates.

A model for clarity of communication

To date, no assessments of the readability of monetary policy texts have been made for the Bank of Russia. In our research, published in the latest issue of Russian Journal of Money and Finance, we set out to create such an instrument, based on linguistic and textual analysis and using machine learning methods.

For this, first of all 10,000 texts were selected, the readability level of which rises from 1 (corresponding to doctors of economic sciences) to 10 (corresponding to junior schoolchildren). This scale was developed by us, but we borrowed the principle of its formation from the classic readability scales. For example, Rudolph Flesch used comic books as the simplest level of complexity and legal contracts as the most complex. We followed the same logic, placing recommended extracurricular school reading lists into readability levels 7-10. In the first, most difficult level we have placed strictly professional economic literature, laws regulating banking and financial markets, as well as monographs on macroeconomics and finance.

We chose 6 as our target level of accessibility, which corresponds to school-leavers. This level includes texts that make up comfortable reading in everyday life: news, blogs, podcasts, telegram channels, modern light reading, Wikipedia articles. These texts should not be difficult to understand for the majority of people.

In this system, we took into account one important nuance. Texts with progressively increasing complexity are required to train the model and, since the model will have to work with economic texts, we include economic texts in the corpus starting at readability level 6. Thus, at levels 7-10 100% of the texts are fiction, at level 6 10% of texts consist of the simplest remarks from the sociopolitical mass media on topics close to the economy (for example, news about an increase in pensions). At levels 1 and 2 all texts deal with strictly economic topics.

From the 10,000 texts we isolate not two fundamental characteristics, as with the classic Flesch-Kincaid scale, but 44. This range is compiled on the basis of Soviet and Russian academic research devoted to identifying what makes text written in Russian difficult, as well as global experience in the development of readability criteria. For our purposes the characteristics are divided into six categories:

- syntax (relates to the structure of sentences)

- lexis (characteristics of discrete words)

- morphology (relates to the structure of the word)

- phonetics (how difficult it is to pronounce this text)

- semantics (identify complexity based on the meanings of words)

- discourse (internal connections within the text and its style, this also includes our classic automated readability scale adapted to the Russian language).

Next, we trained several popular literary models on this dataset, including machine learning models. The best results (95% of texts correctly classified) were demonstrated by a neural network of the "Transformer" class which we had slightly enhanced. Moreover, both the 44 chosen linguistic characteristics and the text itself in a vectorized representation were fed to it as input. For comparison, the classification accuracy on our dataset of the Flesch-Kincaid scale formula adapted (link in Russian) to the Russian language was only 11%.

Assessment of the communication of the Bank of Russia

Overall, the Bank of Russia has done a lot to develop communication. A decade ago, the bank practically never gave any interviews or signals about future policy changes, did not reveal its internal forecasts and analytical workings. Now the regulator adds a new communication tool to its arsenal every year. One of the latest is the transition to holding press conferences after each meeting on the key interest rate (from 2021 they are being held eight times a year instead of the previous four), the publication of information about its monetary policy tools and the predicted trajectory of the key interest rate. Great efforts have also been made to construct a dialogue with a wider audience – communication in the regions, the publication of abridged versions of strategic documents, videos on YouTube are all aimed at this.

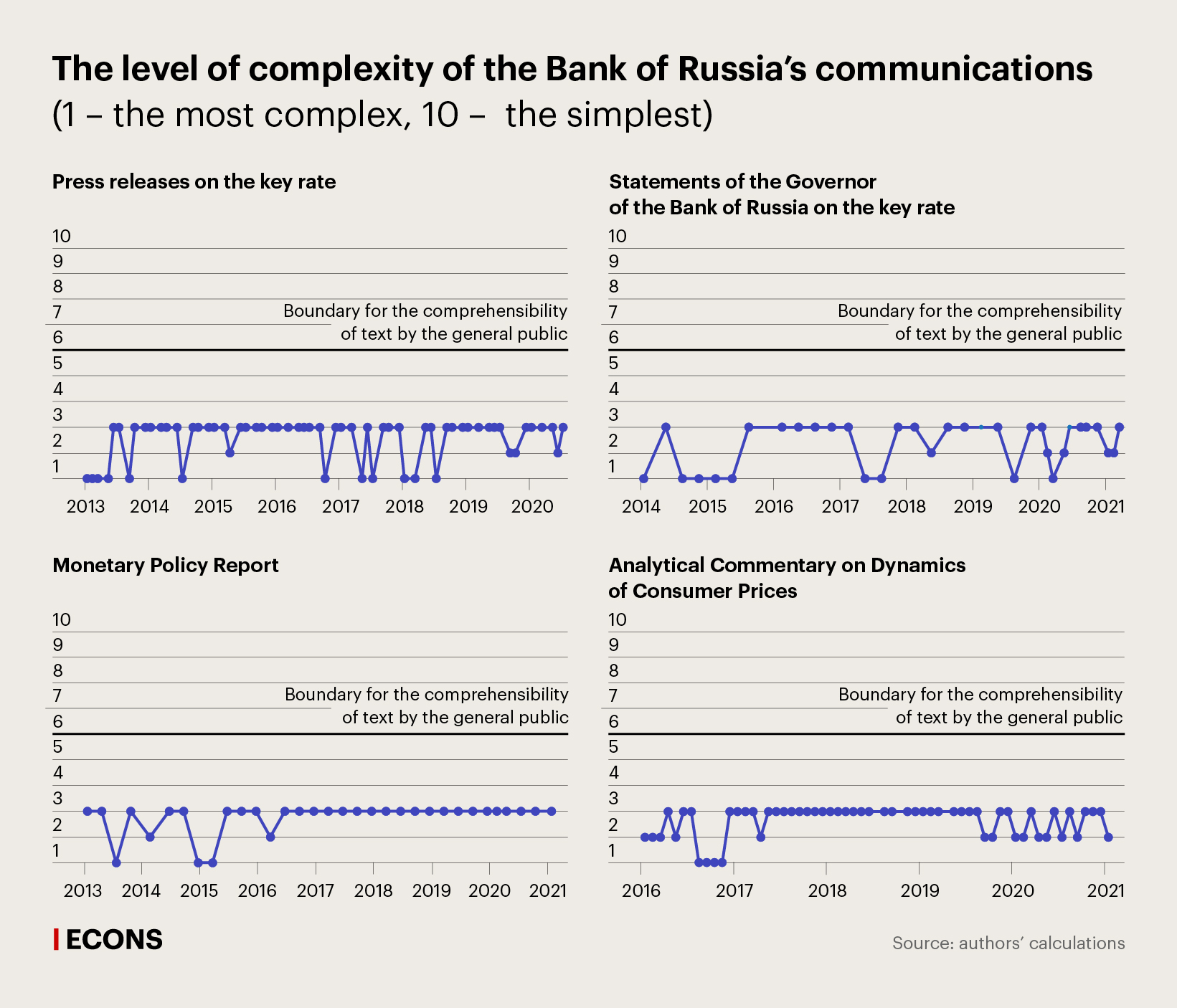

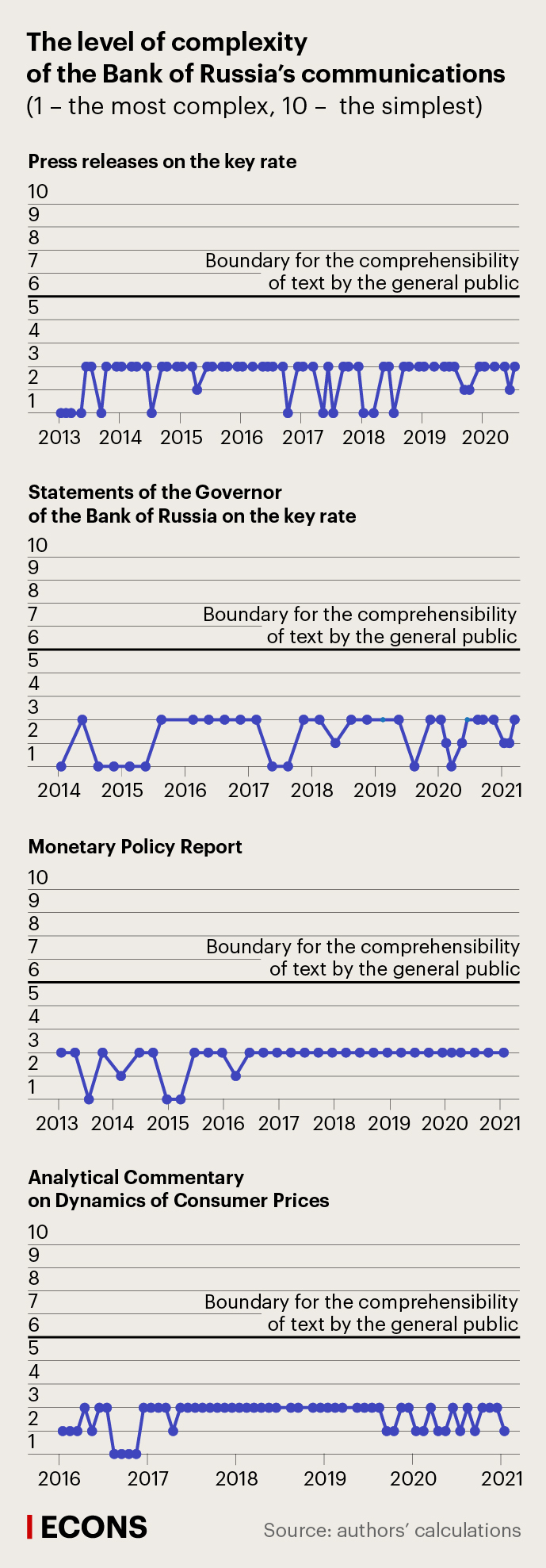

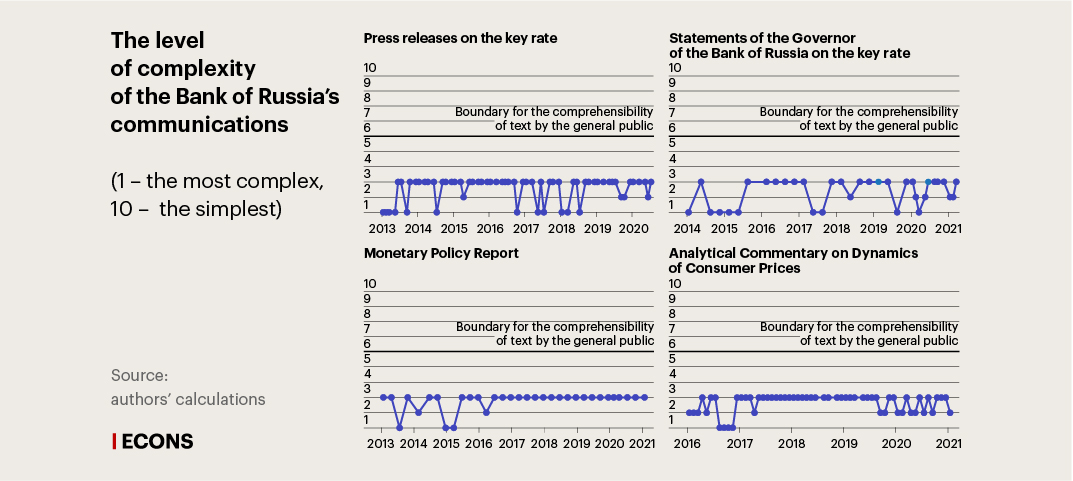

Judging by the data of our model, the potential for a qualitative improvement in the language of these communications is enormous. At the moment the main communications on monetary policy are accessible only to a professional audience. The graphs below show that most communications on monetary policy issues are classified by the model as corresponding to readability levels 1-3, that is only accessible to people with a higher education in economics or even a higher research degree in economics.

It is worth noting that the readability of press releases and statements by the president of the Bank of Russia on the key interest rate may depend on the current uncertainty in the economic situation. Most of the time their readability was at level 3 but worsened during the crisis of 2014-2015, the volatility in the financial markets in the first half of 2018, the VAT hike in early 2019, and the pandemic in 2020. In 2021, German economists from the School of Business, Economics and Society at Friedrich-Alexander University obtained similar results when assessing the readability of statements made by members of the Board of Directors of the European Central Bank.

Of course, one can hardly judge the quality of communication by just the one indicator, readability. Therefore, in the future, the model can be improved by adding the parameters of transparency, document length (there is evidence that long documents worsen communication in general), targeting (of a specific audience). This will give a more complete picture of the quality of the communication of information by the Bank of Russia.

In the meantime, the model we have developed can be used to assess the effects of communication, for example its impact on the volatility of financial markets, on confidence in the central bank and on inflationary expectations. In addition, the model can be used first-hand by the Bank of Russia for the day-to-day assessment of texts. More comprehensible texts from the central bank could contribute to increasing public confidence in the policy being pursued, to improving the predictability of decisions, and to reducing and anchoring inflationary expectations.