Real Estate Market and Monetary Policy: Searching for Balance

Changes in real estate prices and sales, the launch of new projects and the commissioning of new facilities, construction quality, and deadlines are parameters that are all monitored by a wide range of parties (developers, investors, ordinary people, the ministry concerned, financial institutions, and the central bank). Real estate is one of the key assets in the economy, and its special role in our lives makes the real estate market a centre of attention.

First, housing is a basic need for each human being along with the need for safety and food. Furthermore, real estate is one of the few tangible assets that an individual may hold title to. Consequently, residential real estate combines several functions: it is both an asset subject to structural demand, influenced by demographic trends and the condition of the available housing in the country, and a savings and investment vehicle.

The real estate market is a sectoral market, and there is a large amount of literature examining its dynamics from the macroeconomic perspective. However, following a number of economic crises triggered by problems in the real estate market, its macro-criticality has become obvious to economists. This means that the effects of changes in the real estate market may extend beyond it and have an impact on financial and macroeconomic stability in general. However, it is the residential real estate market (see the box) that has become critically important for macroeconomics, as it performs special functions and is characterised by extensive demand, and therefore has systemic effects. The crises associated with the housing market cause more severe drops in GDP and last longer than those caused by other reasons.

The paramount importance of the residential real estate market stems specifically from the fact that it not only connects the real and financial sectors, but also is the object of interest of several types of economic agents. The central bank focuses on this market because it may affect the effectiveness of monetary policy transmission and simultaneously lead to the accumulation of risks to financial stability and, therefore, to economic crises.

The role and the degree on influence of monetary policy on the real estate market has long been the subject of debate. Modern monetary policy is based on managing interest rates throughout the economy, though the real estate market’s response to changes in interest rates may be stronger or more unpredictable than that of economy as a whole. For example, periods of low monetary policy rates have caused overheating or even bubbles in the real estate markets more than once throughout history. The ‘bursts’ of these bubbles have subsequently resulted in economic downturns, of which the US mortgage crisis of 2007–2008 is the most vivid recent example.

This effect of monetary policy on the residential real estate market is precisely a result of the two functions in housing noted above: it is both a basic need and serves as an investment vehicle. When interest rates are low, both of these functions are stimulated. Households that had plans to improve their housing conditions rush to act on these plans. Many others, in turn, see real estate’s investment potential, seizing the opportunity to buy at low rates today for future resale or rental income. As a result, the monetary policy transmission channels may work with double the impact.

Monetary policy transmission channels and demand for real estate

Monetary policy transmission is a sequence of links in the economy through which monetary policy affects demand and, accordingly, inflation. The monetary policy transmission mechanism has several channels through which it impacts the real estate market in particular.

- The interest rate channel. This is a basic monetary policy transmission channel associated with the direct impact of interest rates on decisions to consume, invest, and save and, therefore, on demand in the economy and inflation.

As regards the residential real estate market, the interest rate channel affects decisions to purchase housing and take out mortgage loans. For example, when interest rates are low, it is easier to choose between current consumption and future loan payments. The interest rate channel allows financial institutions to draw conclusions about the interest burden and, therefore, whether it will be easy for borrowers to repay their loans.

- The balance sheet channel. The changes in the central bank’s interest rate trigger a revaluation of the value of collateral, which in turn influences loan demand and, consequently, aggregate demand in the economy.

The real estate purchased also serves as loan collateral. If housing prices rise, the value of the collateral also increases, which is common when interest rates decline. Consequently, a credit institution’s willingness to issue mortgage loans and the loan amounts themselves may increase. When interest rates go up, a reverse trend will be observed.

- The welfare channel. This works through income from assets. For example, when the stock market grows amid accommodative monetary policy, investors’ incomes also rise. In turn, gains from asset appreciation may affect current consumption, i.e. demand.

The cost of money, as determined by the central bank’s interest rate, may increase demand for real estate. The rise in home prices boosts the wealth of existing homeowners, thereby expanding their ability to take out loans, such as to purchase additional property or to upgrade their current homes.

- The risk-taking channel. Changes in monetary policy interest rates may effect economic’ agents risk perception and tolerance and, consequently, the level of risk in asset portfolios as well as the pricing of financial instruments and the price and non-price conditions for the provision of loans. For example, monetary policy easing may boost the appetite for risky investment, while tightening tends to dampen it.

In the real estate market, when monetary conditions are eased, financial institutions are more inclined to grant loans, since low interest rates reduce the likelihood that borrowers will face unfavourable events (such as the loss of a job) and therefore fail to repay their loans.

- The expectations channel. The central bank’s words and actions concerning monetary policy affect economic activity through this channel, changing the expectations (link in Russian) of economic agents. For example, expectations of tighter monetary policy may reduce consumption (and thus inflation), whereas expectations of looser policy lead to the opposite.

The interest rate channel generally dominates the economy. However, the real estate market, like any other asset market, experiences a notable effect from the expectations channel. Normally, lower interest rates work through the expectations channel to boost optimism about the economy’s growth potential and encourages the expansion of activity right up to the point where physical resources become the limiting factor.

However, a drop in the interest rates followed by a rise in demand and an inflow of funds to the real estate market may lead to the disregarding of physical resource constraints. At a certain point, the opinion may start to prevail that demand will inevitably keep rising partly under the function of housing as the basic need that will never cease to exist. This buyer behaviour is sometimes called ‘irrational exuberance’ – demand in the asset market pushes prices up, which in turn fuels demand even more, ultimately resulting in a bubble. Since, in such cases, buyers are often guided by their sentiments rather than rational analysis, it is fairly difficult in practice to determine in advance when elevated demand will transform into ‘irrational exuberance’.

We can say that, in this case, the expectations channel actually starts to prevail over the risk-taking channel, thus causing economic agents to underestimate the risks taken. Borrowers undertake financial obligations without due regard for their ability to meet them, and credit institutions simplify the audit standards they apply to borrowers and ease the requirements for supporting documentation. For example, during the US mortgage crisis in 2007–2008, when interest rates were low, financial institutions actually turned a blind eye to the risk taken and issued mortgage loans practically without auditing the borrowers.

This combination of transmission effects provides evidence that in the event of low interest rates, the impact of monetary policy on the real estate market may be stronger than is needed for economic activity to return to potential growth rates.

The monetary policy rate is a comprehensive, rather than a targeted, instrument. Therefore, to offset its impact in individual markets and prevent crises resulting in part from imbalances in the real estate market, central banks began to introduce macroprudential regulation from 2008 in pursuance of their policy of maintaining financial stability. Macroprudential policy measures include, for example introducing minimum down payment requirements for mortgages used in home purchases, setting debt ceiling for households applying for loans, using macroprudential risk weight add-ons, and limiting the number of loans issued to individual types of borrowers.

Nevertheless, monetary policy and macroprudential regulation remain separate areas, each with its own goals and focuses. Monetary policy manages interest rates to achieve the inflation target, while macroprudential regulation aims to reduce the vulnerability of the financial system.

Therefore, targeted measures of financial stability policy adjust the distortion of the risk-taking channel resulting from the strong effect of the expectations channel. While macroprudential regulation can constrain or weaken the impact of certain monetary policy transmission channels, these constraints are highly beneficial for an overheating real estate market and even make it more stable.

Nevertheless, even though the introduction of macroprudential regulation made it possible to offset the drawbacks of monetary policy during the low-rate cycle, it has not solved all the issues associated with the effects of monetary policy on the real estate market. When monetary policy is loose, macroprudential regulation primarily serves to adjust demand, i.e. to eliminate overheating and risks to financial stability. However, not all imbalances in the real estate market stem from the demand side. Supply plays an important and sometimes a greater role. Recently, more researchers have been specifically analysing the impact of monetary policy on the supply of real estate.

Investment and construction cycle: specific features of monetary policy transmission

Housing construction is a lengthy process, spanning years from the design of a particular residential project to its completion. The process of finding a suitable land plot, drafting planning documentation, navigating different regulatory approvals, obtaining land use permits, conducting engineering studies, and preparing project documentation, which developers must complete before construction can begin, is a typical scope of work that may take roughly two years. Construction itself takes an additional two to three years. Furthermore, residential construction is different from other industries, as changing a building’s original design or purpose is far more difficult, in part because of the sector’s unique regulation.

It is therefore impossible to quickly ramp up the supply of real estate, while demand may change in several months, since it may rapidly adapt to changes in interest rates and other macroeconomic conditions. Housing supply adjusts to demand with a considerable lag. Consequently, the cycle of supply and demand for housing may move out of sync with the economic cycle. These swings between supply surplus and deficit may become a self-sustaining source of imbalances.

The disparity in how quickly supply and demand respond suggests that the conditions for market overheating and potential bubbles begin to form not when interest rates are cut, but significantly earlier. A supply deficit itself may be a significant prerequisite for a rise in prices and a subsequent bubble.

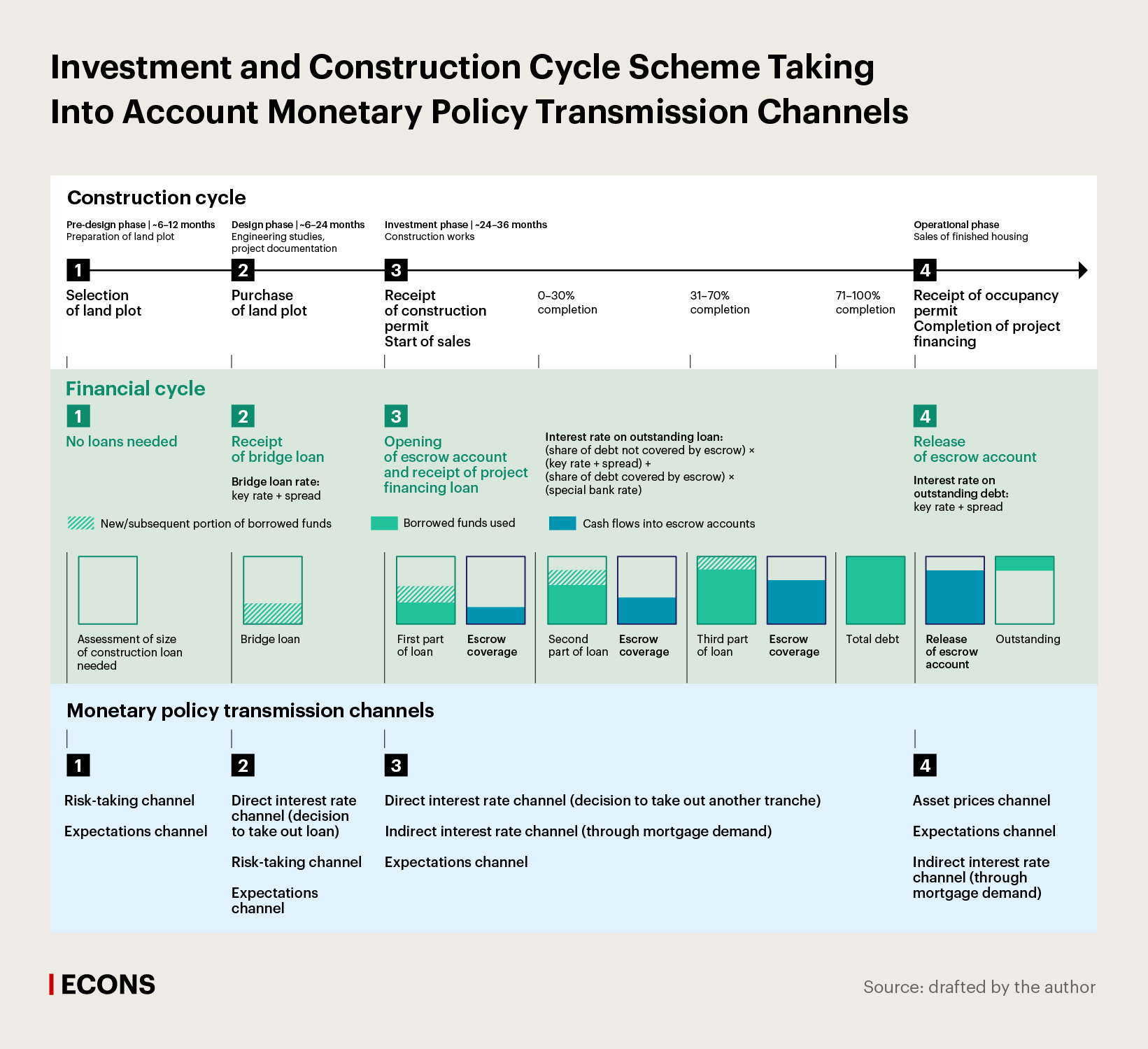

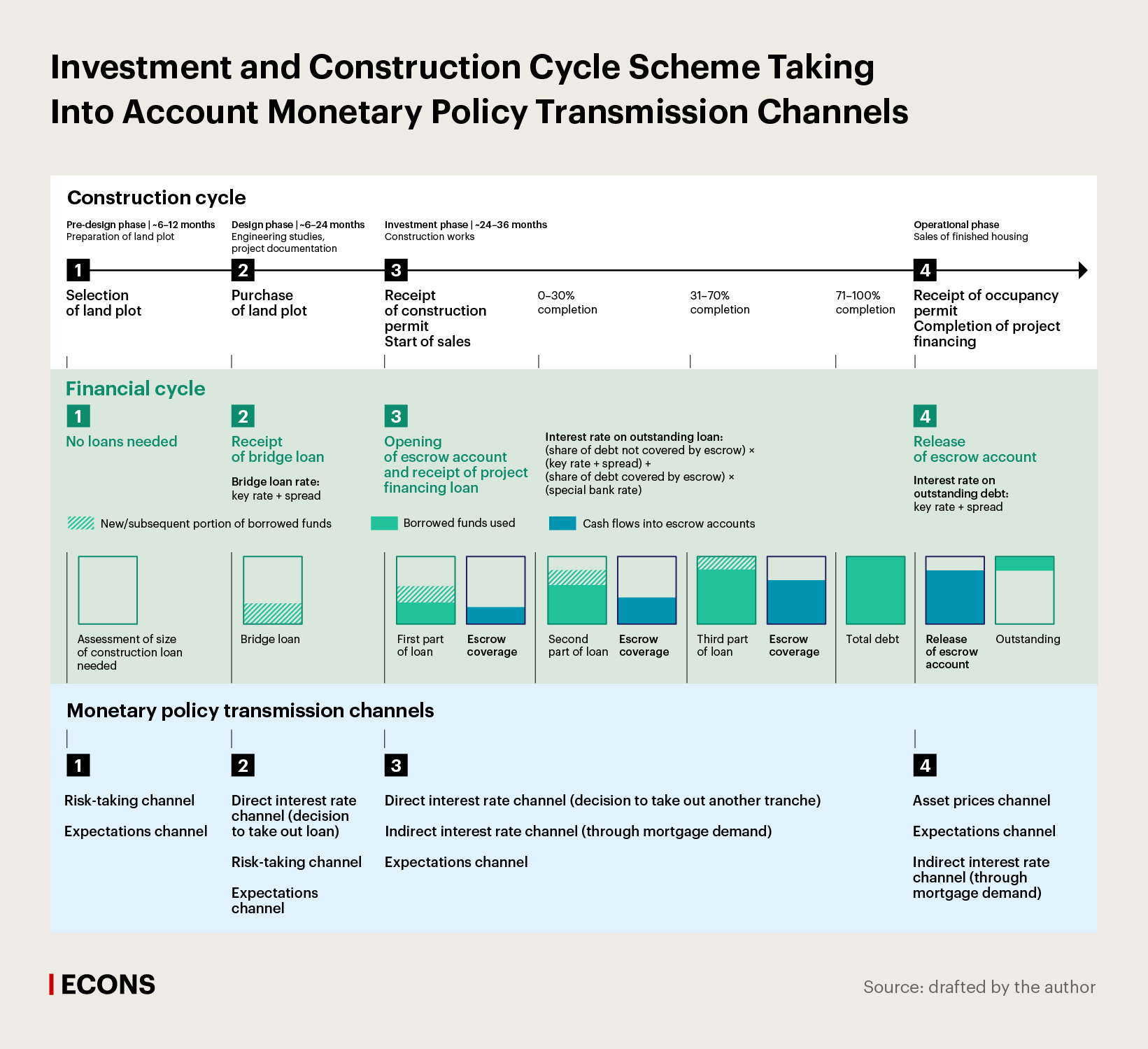

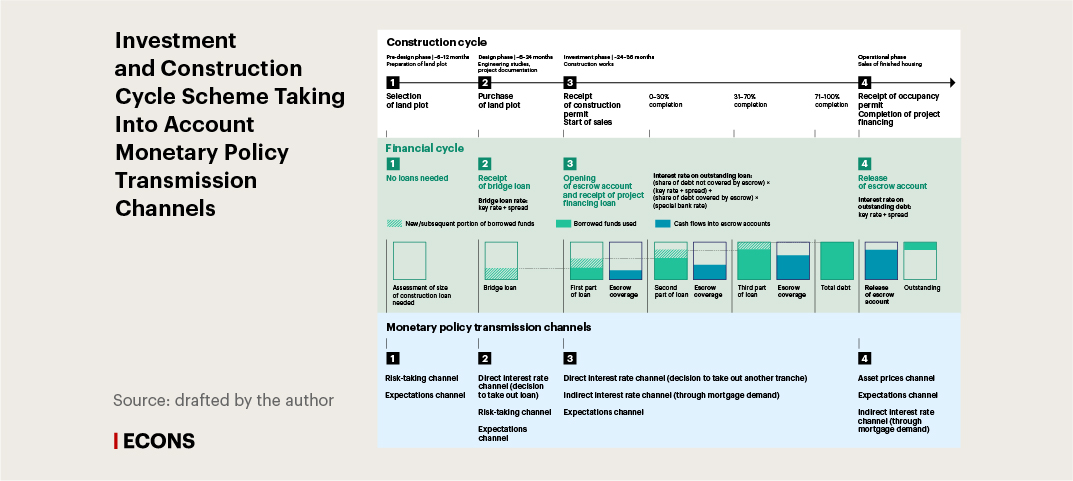

How might a housing supply deficit be linked to monetary policy? It is more convenient to demonstrate this relationship through the example of the investment and construction cycle for apartment buildings in Russia (see the diagram below). This cycle can be tentatively broken down into four stages: the pre-design phase, the design phase, the investment phase, and the operational phase. The impact of monetary policy varies across the different phases.

- In the pre-design phase, the developer decides to commence the project, searches for a suitable land plot, assesses the loan amount needed and the possibility of generating profit. There is no urgent need for a loan yet, so the expectations and risk-taking channels dominate at this stage. The lower the rates, the more optimistic the expectations, and the greater the willingness to commence the project. When interest rates are high, new construction projects start to lose their attractiveness at this stage.

- In the design phase, the developer decides to launch the project and purchases the land plot. Before construction begins, the land must be prepared and documentation must be drafted. At this stage, the developed takes out what is called a ‘bridge loan’ – a short-term loan to finance the expenses (for purchasing the land plot, clearing the territory, etc.) before the construction permit is obtained. The bridge loan rate is aligned with the standard corporate loan rate (i.e. the key rate plus the spread, which factors in the risk premium and operating expenses). Therefore, in the design phase, the interest rate channel fully comes into play alongside the expectation and risk-taking channels. If the developer expects that it will pay a high interest rate throughout the entire design phase (for around two years), it will not be very interested in purchasing land for development, and the volume of new projects will go down.

- In the investment phase, after obtaining a construction permit, the developer starts the construction of the building and is also allowed to start sales. The interest rate channel is also operative here, albeit in a somewhat specific manner. At this stage, the developer converts the bridge loan to a construction loan through project financing. The project financing mechanism ties the loan rate to sales: proceeds from the sales of the units are credited to escrow accounts (link in Russian). These funds remain inaccessible to the developer until the project is completed but are recorded as liabilities on the balance sheet of the lending bank. This allows the bank to apply a special discounted interest rate to the portion of debt equal to the amount held in escrow. The remaining part of the debt is subject to the standard interest rate (the key rate plus the spread).

Consequently, the higher the sales, the lower the rate. The interest rate channel thus impacts early-stage construction projects in two ways: through the developer’s own financing and through the homebuyers’ mortgages. A decline in the monetary policy rate boosts demand for mortgages, which in turn, increases the balances in escrow accounts and additionally reduces the interest rate for the construction company. A rise in the rates has the opposite effect, with high mortgage rates leading to low sales and higher loan rates for project financing.

Furthermore, since loans are granted in instalments (tranches), rather than as a single lump sum, developers can control the interest rate by slowing down the lending process, i.e. hold off on requesting the next tranche until a sufficient amount is accumulated in the escrow account. The expectations channel takes effect here: expectations of further monetary policy tightening encourage developers to slow down construction. The slowdown strategy may be applied both at the initial stage and at later stages. If the construction is close to completion and the sales do not cover the loan amount, slowing down construction helps the developer benefit from the rates under the escrow mechanism for a longer period. When the building is commissioned and the escrow accounts are released, i.e. when the funds are obtained, the developer pays the higher standard interest rate (the key rate plus the spread) on the remaining portion of the debt.

It is generally accepted that under normal circumstances, when the project is completed, the escrow account balance should at least cover the developer’s project financing if around 70% of the units are pre-sold, and the developer can sell the remaining units for profit. The fewer the units that are pre-sold when the project is completed, the higher the probability that the debt will be repaid at a higher interest rate. In other words, during high-interest rate periods the interest rate channel makes developers slow down construction, thus reducing total supply.

- In the operational phase, the developer obtains a certificate of occupancy and sells the remaining housing. The asset prices (welfare) and expectations channels have stronger effects here. The higher the expectations of a rise in real estate prices, the faster the flats will be sold, and the developer will be more inclined to start a new project. The interest rate channel still has an indirect effect through demand for mortgage loans. The more slowly the flats are sold (in part due to high mortgage rates), the weaker the developer’s appetite for new projects. However, the impact of this phase on supply is comparatively insignificant.

The investment and construction cycle means that, in deciding to commence a construction project, a developer must answer the key question of whether there is a balance between the cost of the construction loan and medium-term demand expectations. In addition, the sector is very inert.

A period of low rates may long ensure the commencement of new projects even after the rates go up. The pre-design work will encourage developers to move to the investment phase, which allows them to start sales and thus reduce the interest burden.

Contrastingly, a long period of high rates in the economy may discourage developers from launching new projects and slow down current construction. This in turn will decrease supply for the next two to three years – even after the rates go down, there will remain lags of the time that are necessary for conducting preparatory work. The lengthy design and pre-design phases mean that neither the supply of finished housing nor the overall construction portfolio can expand quickly in response to lower rates and stronger demand. Therefore, to some extent, supply shocks in the housing market are shocks with a time-lag effect.

If, when rates are low, stimulating demand, the supply is still at the stage when permits are being secured, the land is being prepared for construction, and the housing cannot be purchased, there is an imbalance between supply and demand. The time-lag effect of negative supply shocks combines with growing demand.

Consequently, monetary policy has a stronger effect on the real estate market than on the economy overall, no matter whether the rates are low or high. Monetary policymakers trying to regulate this market may be walking on thin ice.

Ensuring balance

What is to be done in this case? As stated above, central banks tighten macroprudential policy to prevent bubbles when rates go down. However, this does not solve the main problem – the supply deficit. At the same time, it can hardly be solved by applying macroprudential measures, and monetary policy is sure to be ineffective, since real estate is a sectoral market and monetary policy cannot be tailored to target a specific market even if it is macro-critical.

There is no simple solution, and a set of complementary measures is required. This is why the governments of almost all countries strive to develop the housing market and support it using various methods due to its overall social significance. In designing support measures, policymakers should be guided by two core principles: keeping the measures targeted and ensuring the long-term market balance control. An ill-conceived development and support programmes will not only fail to improve the situation but also worsen the existing imbalances.

The situation in the Chinese real estate market can serve as an example of an imbalance caused by regulation. China was trying to simultaneously achieve two goals: developing the real estate market and topping up local budgets. For many years, the incomes of municipalities were heavily dependent on land sales. Local authorities aimed to sell as much land as possible and sometimes helped developers take out land loans. This increased developers’ debt burden and caused an excessive rise in the supply of real estate. For a time, this rise was absorbed by expanding investment and, in certain cases, speculative demand. The introduction of debt limits for developers resulted in the bankruptcy of a number of large developers. The turbulence in the market triggered a sharp contraction of demand and lots of unfinished buildings.

The Russian housing market is relatively young. It has been using the mechanism of escrow accounts for slightly more than five years. However, this period has been enough for policymakers to see both the advantages and pitfalls of large-scale support programmes for the real estate market. The government subsidised mortgage programme launched in 2020 prevented a market shut-down. When the pandemic hit it, the market was immature: the transition to project financing had only begun, and the adjustment of processes was still underway. However, the programme remained in effect after the threat of market contraction had been overcome. As a result, excessive demand for new housing affected prices more significantly than the expansion of supply, and the prices for new housing doubled (link in Russian) when the programme was in effect. This is another piece of evidence that, after rates are cut to encourage demand, price growth and the risks of overheating become more notable than the rising affordability of housing.

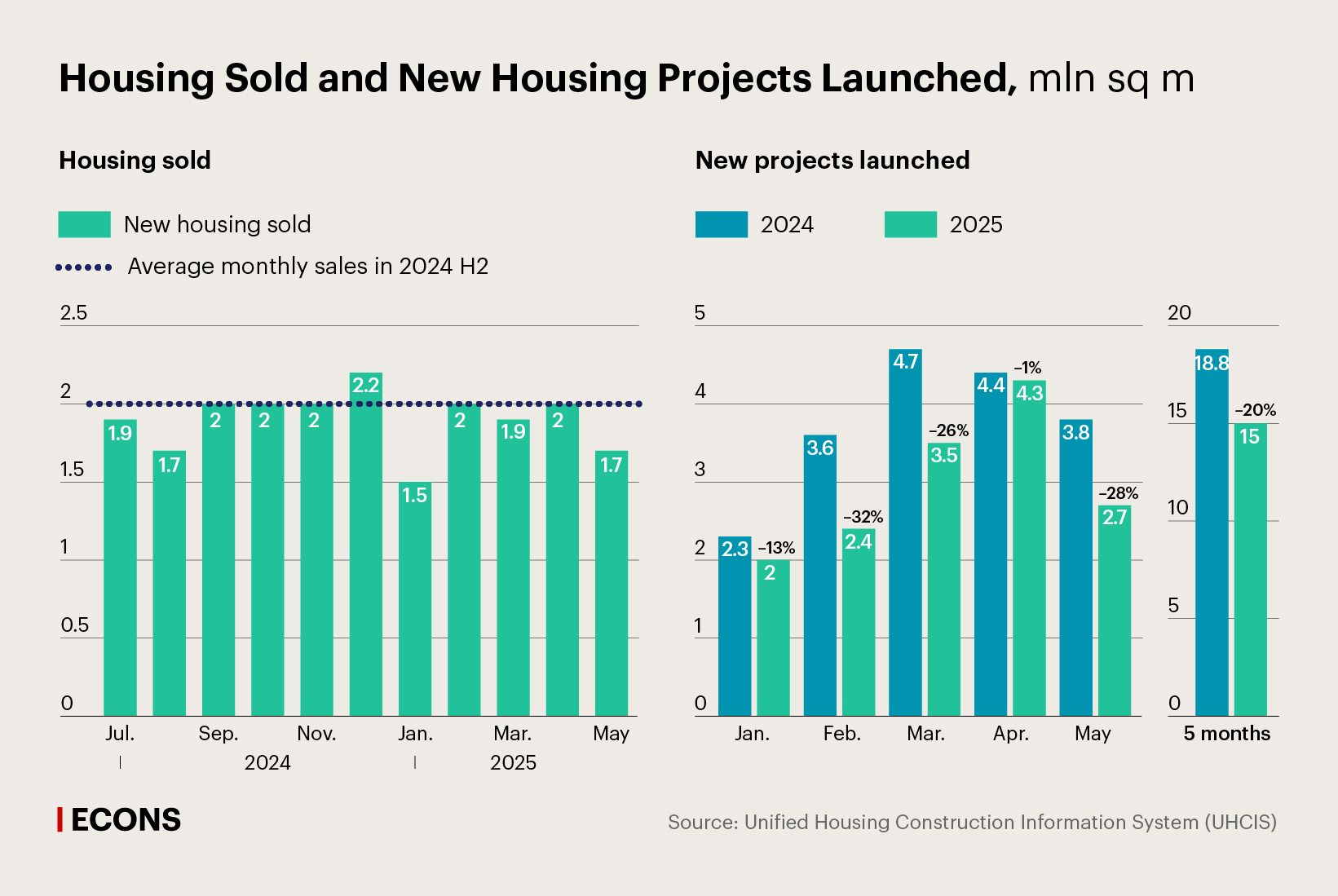

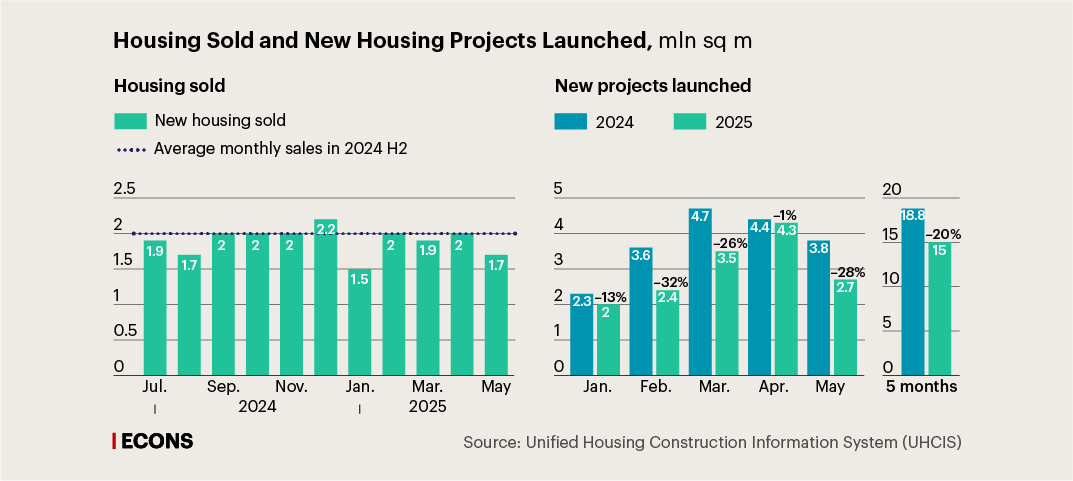

The Russian real estate market is now going through a phase of high rates for the first time. Demand is fuelled by targeted mortgage programmes (Family Mortgage, Far Eastern Mortgage, and IT Mortgage). For almost a year since the July 2024 drop, when the large-scale government subsidised mortgage programme was terminated, sales have been averaging two million square metres per month, with a slight decline in 2025.

Concurrently, the high rate has caused a gradual decrease in the number of new projects. Over the first five months of 2025 (link in Russian), the number of new projects went down by 20% year on year. The number of projects whose commissioning deadlines are being moved has also been rising, although less notably.

Demand for residential real estate in Russia is basically determined by fundamental factors, such as low housing availability, a large share of worn-out housing, and the high housing obsolescence rate. Therefore, if the rates fall to 12–15%, market demand growth, which is now close to multi-year lows, may increase sales to the 2021–2023 averages (around 28–29 million square metres per year), i.e. by 20–30% as compared with the potential sales in 2025. According to current project launch data, the construction portfolio may contract by that time, probably by 15–20% as compared with the 2025 figures. Consequently, a rise in prices amid a real estate shortage is a highly likely medium-term scenario. Probably, it is time to take measures to support supply with a view to mitigating future imbalances.

For example, simplifying and eliminating excessive regulation would reduce the time needed to obtain permits and approvals from city planning commissions and thus shorten the pre-design and design phases, which would help developers embark on new projects more quickly when the rates go down.

Furthermore, it is worth considering a temporary rate subsidy programme for projects in the early investment stage. Subsidising such projects would help avoid a sharp decrease in the number of new projects launched and prevent a drop in supply in the future without excessively stimulating current demand.

As regards long-term measures, it would be prudent to develop the market for long-term institutional rental, which is affordable and convenient. This approach would reduce the pressure of finding housing and thus mitigate the imbalances between supply and demand. In addition, increasing the variety of available housing options through quicker-to-build developments (low-rise and single-family homes), coupled with improving the surrounding infrastructure, will help ease demand pressure on the market for flats.

The real estate market is increasingly being discussed by various economic policy agents. The expansion of the market may trigger more disputes about the impact of monetary policy on housing supply and demand, time-lag effects, the combined effect of different policies, and the elimination of imbalances.

However, despite possible tactical disagreements on applicable measures, any housing policy has the same goal: to foster a stable housing market that makes a meaningful contribution to the economy, no matter the interest rates.