Despite significant changes and the exit from the market of a number of important players, such as international companies and regulatory organisations (e.g., International Capital Market Association, ICMA), Russia has managed to keep the sustainable development agenda relevant. Following the Taxonomy of Sustainable Finance Projects adopted (link in Russian) in 2021, the Russian government also approved a social taxonomy (link in Russian) at the end of 2023, which should become an alternative to the international standard that was previously used for social bond offerings in the Russian market. The document remains merely a recommendation and needs to be supported by a system of benefits for the initiators of social projects, as for now only the effect on image is clearly visible, which those companies that have already included social loans in their portfolios are likely to agree to.

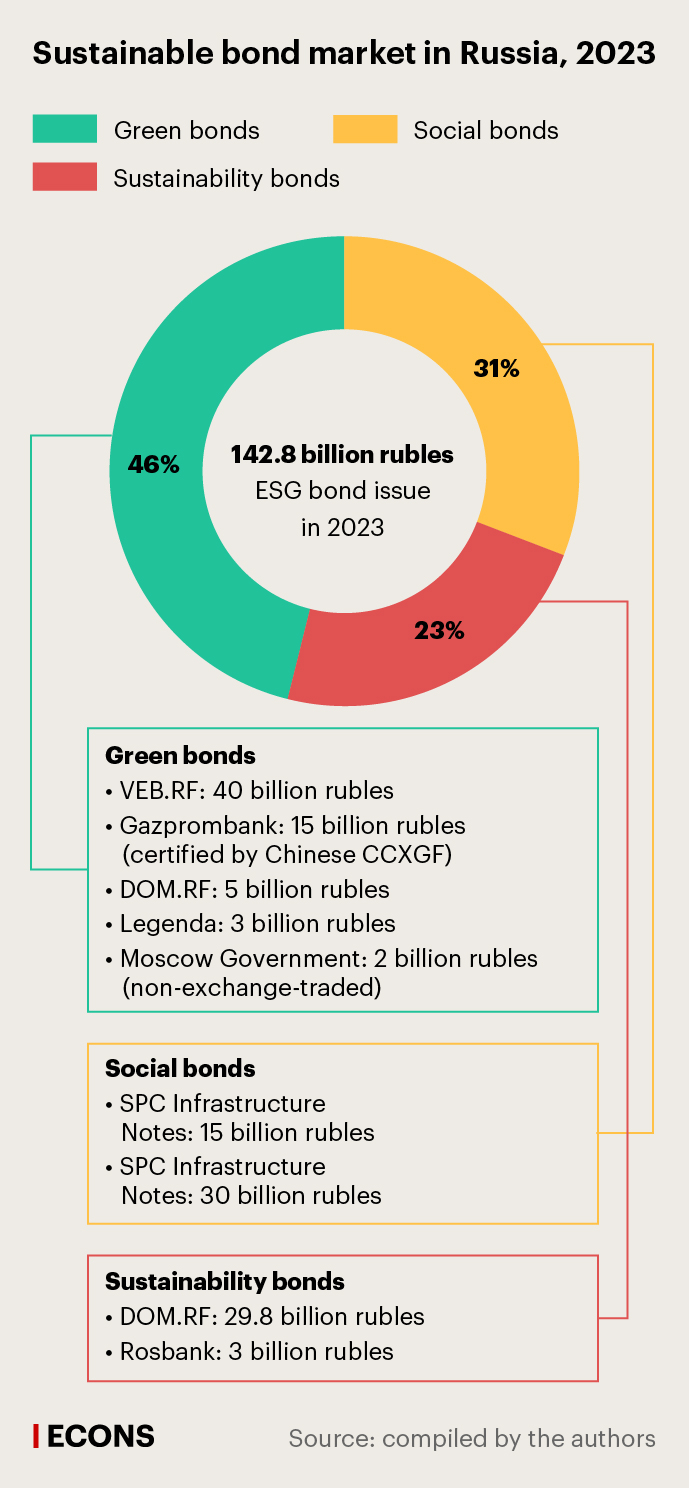

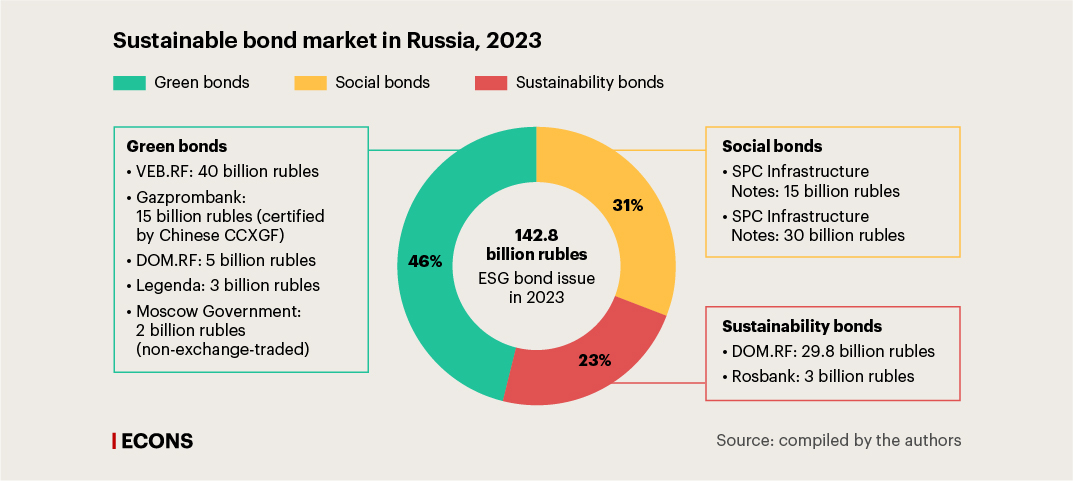

There are quite a few such companies: according to the data (link in Russian) of Analytical Credit Rating Agency (ACRA), social bonds accounted for 31% of the total sustainable bond issuance in 2023. Another 23% were sustainability bonds whose proceeds are used to finance or refinance combined green and social projects. Green bonds accounted for the largest share of the total issuance (46%). ESG bonds issued in Russia in 2023 totalled 142.8 billion rubles, which is 34.5% more than in 2022. The market reached (link in Russian) nearly 490 billion rubles by the end of 2023.

A new financial instrument appeared in the Russian market in 2023: Rosbank and DOM.RF became the first (link in Russian) issuers of sustainability bonds in Russia. The green bond segment also saw a significant debut: Gazprombank’s bond issue was certified (link in Russia) as compliant with the ICMA Green Bond Principles and the Russian taxonomy by China Chengxin Green Finance Technology (Beijing) Ltd (CCXGF). This was the first time since 2022 that a Russian issue received international certification and the first issue in the history of the Russian market to be certified by a Chinese certification agency. Importantly, Chinese certification agencies use internationally accepted green principles as the basis for their criteria, so Gazprombank’s green bond issue is technically no different from those certified by Western organisations. This is a good case for Russian companies that are thinking of starting doing business in Asian countries.

Experts differ in their assessments of the prospects for the issue of sustainability bonds in 2024. ACRA believes (link in Russian) that the issue will reach 200 billion rubles. Expert RA forecasts (link in Russian) that there will be at least five offerings of ESG bonds in 2024 and that the market will amount to 550 billion rubles, thus growing by 60 billion rubles compared to last year.

In addition to the unfavourable geopolitical situation, the absence of the ‘greenium’ effect (link in Russian), the willingness of investors to pay a premium for green instruments, also acts as a constraint and a risk factor for the Russian market. The interest rate on green bonds has not been lowered compared to other bonds, and the government does not reimburse the certification costs. Hence, it is too expensive for companies to issue sustainable bonds. In addition, by July 31 the Bank of Russia’s key rate has increased by 10.5 percentage points compared to H1 2023 to 18%, which makes issuing sustainable bonds even less profitable. This, however, has not prevented the emergence of new green finance instruments that support the agenda and attract more and more financial institutions.

Green lending

One such instrument is green lending where the borrower undertakes to use the funds raised to finance or refinance green projects. Sber was one of the first to launch green loans in 2020, and in 2023, its portfolio included (link in Russian) green, adaptation, social, and ESG loans totalling over 2.4 trillion rubles, compared to 1.3 trillion rubles the year before.

According to the bank, construction sector companies (56% of the ESG loan portfolio) were the most likely to apply for green loans in 2023. A survey of the top 10 large housing developers, conducted (link in Russian) by a consulting company Kept, showed that half of the respondents were already using some green technology and that half of this 50% planned to expand its use. The amount of green lending can be expected to grow as the construction industry, considering its substantial influence on the environment, should stay flexible in terms of the ESG transformation.

According to the calculations of the International Finance Corporation (IFC), a member of the World Bank Group, the transition to green building could help reduce greenhouse gas emissions (including in Russia) by about 25% by 2035.

Green mortgages

The green mortgage is another instrument that is new in the Russian market. Green mortgages are intended for the purchase of sustainable housing which is built using a special approach to the design, construction, and further maintenance of the building (high energy efficiency, environmentally friendly materials, etc.).

DOM.RF is responsible for the implementation of the Russian national policy to improve the affordability and sustainability of housing and was the first to start issuing green mortgages. According to the bank’s calculations, about 25% (link in Russian) of its mortgages are already used to purchase housing in energy-efficient buildings. In 2022, the bank made its first issue of green mortgage-backed bonds: loans issued for the purchase of flats in energy-efficient buildings were included in the mortgage pool of these securities. The purpose of such offerings is to allow banks to refinance green mortgages.

The green mortgage market is a promising area for sustainable development efforts: so far, only a limited number of Russian banks offer mortgage loans of this kind. The interest rate on mortgages for the purchase of flats in energy-efficient buildings is 0.3–0.5% lower than the rates on other mortgages.

Green prospects and international practice

The world is witnessing the emergence of new green financial instruments that could potentially become popular in the Russian market.

- Green deposits.

The main difference between green deposits and other types of deposits lies in the fact that banks can use green deposit funds only for specific purposes. Green deposits began to appear around the world in the early 2020s. In Hong Kong, one of the largest Chinese banks – the Bank of China – invested about $605 million of customer green deposits in green building, pollution prevention, and sustainable agriculture projects from January to September 2023. In Germany, Deutsche Bank introduced green deposits in 2021: the funds raised for green projects through these deposits from January 2021 to June 2022 totalled €516 million ($553.4 million), of which 84% were used to finance green construction. Green deposits are growing in popularity in India, Japan, the USA, and Australia. Center-invest Bank was the first to offer green deposits in Russia in 2020, with this banking product remaining rare in the Russian market.

- Green savings accounts.

These savings accounts are offered by several banks in Hong Kong, Bangladesh, Latvia, and Indonesia. The funds held in green savings accounts are invested in sustainable projects and energy-efficient real estate. This instrument is not yet common in the Russian market.

- Green pensions.

The pension contributions of working citizens, concentrated in both private and public pension funds, may be channelled into ‘greening’ the economy, i.e., invested in green bonds. According to a statement by Make My Money Matter, a British public campaign that tracks the climate plans of pension funds, making pensions green is 21 times more efficient in terms of reducing CO2 emissions than avoiding air travel or changing energy suppliers. However, access to this instrument is still limited in the UK. Potentially, this instrument could be considered for in the Russian market as well: this type of investment could become sought after among the younger generation, which is sceptical (link in Russian) about future pensions and more environmentally conscious.

- Measures to support small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) in their transition to a sustainable development path.

These measures could also facilitate the development of a green finance market. Malaysia has relevant experience: Capital Markets Malaysia, an affiliate of the Securities Commission Malaysia, issued a Simplified ESG Disclosure Guide for SMEs in October 2023. Malaysia has thus become the first country in the world to provide SMEs with a simplified and standardised package of ESG disclosure guidelines. All recommendations are categorised into three levels: basic, intermediate, and advanced, which allows businesses to prioritise better and gradually shift from one disclosure level to another. The guide has already been adopted by many Malaysian banks offering green loans to companies that have implemented these recommendations: the lending rates for such borrowers are lower. For example, Alliance Bank approved loans worth RM200 million ($42.5 million) to Malaysian SMEs for green projects in fiscal year 2023 and is committed to doubling this amount in 2024.

A similar instrument adapted to the Russian market is long overdue: so far, the burden of educating SMEs on sustainable development principles has been solely on large businesses. Most of them are tackling (link in Russian) this challenge by updating their supplier codes of conduct and greening supply chains. Small businesses point out that there are no tax incentives or legislation to encourage them to put time and effort into achieving this objective. Incentivising banks to provide reduced-rate green financing to companies with ESG strategies could lead to an increase in the number of such businesses.

- Green insurance.

Green insurance involves lower insurance premiums for green businesses and practices. This product is increasingly used around the world, especially after the United Nations Environment Programme Finance Initiative (UNEP FI) published the Principles for Sustainable Insurance, a framework for insurers to address environmental and social risks. Examples of green insurance include green property insurance where insurers offer discounts to home owners to encourage green building and reduced energy consumption, or fuel saving discounts to those who use electric or hybrid electric vehicles.

Other than green

In early 2024, the Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment of Russia presented (link in Russian) its draft Water Strategy of the Russian Federation until 2035, which was discussed by experts until 17 April. During this discussion, the experts proposed the introduction of a new concept – a blue economy – to subsequently facilitate the launch of blue bonds. The proceeds from offering blue bonds are to be used to support ocean health and the blue economy through addressing environmental issues (sewage treatment, removing waste from the ocean, and preserving marine biodiversity), developing sustainable fisheries and aquaculture, sustainable shipping and construction of port infrastructure; and modernising water supply systems.

According to a study (link in Russian) by Promsvyazbank and VEB, the development of the ‘blue economy’ agenda in Russia is still in its initial stage, although the taxonomy of green projects includes activities related to water management. The authors of the study note that ‘blue bonds’ have been part of international practice for quite a short time, namely since 2018. They are issued by both international financial institutions (including the World Bank and the Asian Development Bank) and private corporations (e.g., seafood companies in Japan and Norway). In 2022, the number of blue bond issues reached 11 (for comparison, there were only two issues in 2018), totalling $1.5 billion.

The concept of blue bonds needs to be institutionalised at the government level. Russia already has a Maritime Doctrine in place (link in Russian), adopted in 2022, which is a strategic document outlining the country’s maritime policy. The doctrine states that the national interests include ensuring environmental safety when operating in the world ocean, but it does not provide much detail on the topic. The water strategy could potentially become a regulatory framework for the development of the blue bond agenda in Russia.

Russia has great potential for the development of the ESG finance market both at the corporate and government levels. Green bond issuance is growing, new issuers are emerging, and green mortgage lending is expanding, while banks are testing new financial instruments such as green deposits. The level of activity of businesses and financial institutions despite the sanctions pressure is evidence of the development of the market and indicates a readiness to work with new partners. Given the constantly evolving legislation on climate policy and non-financial reporting, the above mentioned financial instruments have a chance of being introduced in the Russian market.