Green Transition: Confirming the Priority

The global economy is going through difficult challenges. They have emerged with the onset of the pandemic and intensified on the back of Russia’s ongoing special military operation in Ukraine, which triggered the imposition of anti-Russian sanctions. The current challenges include disruptions in production and supply chains, rising energy and food prices, multi-year highs of inflation in advanced economies, and debt risks amid debt overhangs and the mounting cost of financing in global markets. No wonder central banks around the globe have concentrated their efforts on delivering price and financial stability.

Nevertheless, climate change, which became a part of central banks’ agenda a few years ago (link in Russian), is still relevant in this new reality; all the more so, as major economies are willing to ramp up their efforts to facilitate the transition to a low-carbon economy. This was confirmed by the second Green Swan 2022 conference held this June by the Bank for International Settlements (BIS), the European Central Bank, the Network for Greening the Financial System (NGFS) and the People's Bank of China. The energy transition is currently complicated by the energy crisis and rising prices for most goods – both socially significant products and those used in green energy. Yet, this complication appears to be a short-term challenge. Instead, over a medium and long term, high fuel prices are set to incentivise the rapid development of renewables.

The climate agenda remains important to Russia, with its fuel and energy sector accounting for a high share in GDP, though its short-term priorities are to refocus exports on new markets and ensure the economic transformation. In previous years, the key channel of climate transition risk for Russia was the introduction of cross-border carbon tax in the EU due in 2026; yet, in the context of EU sanctions these risks are expected to materialise much sooner and in the most conservative form.

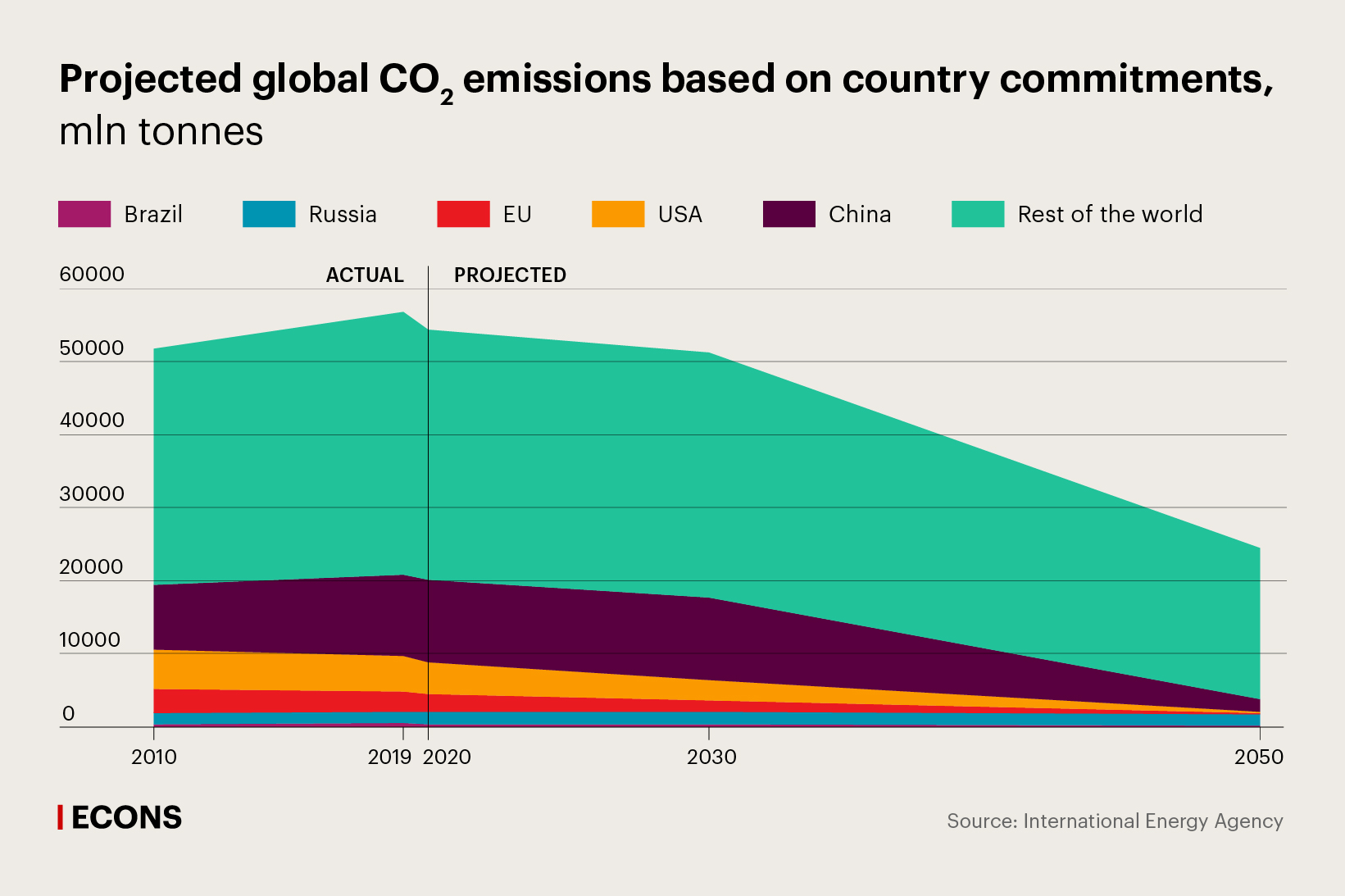

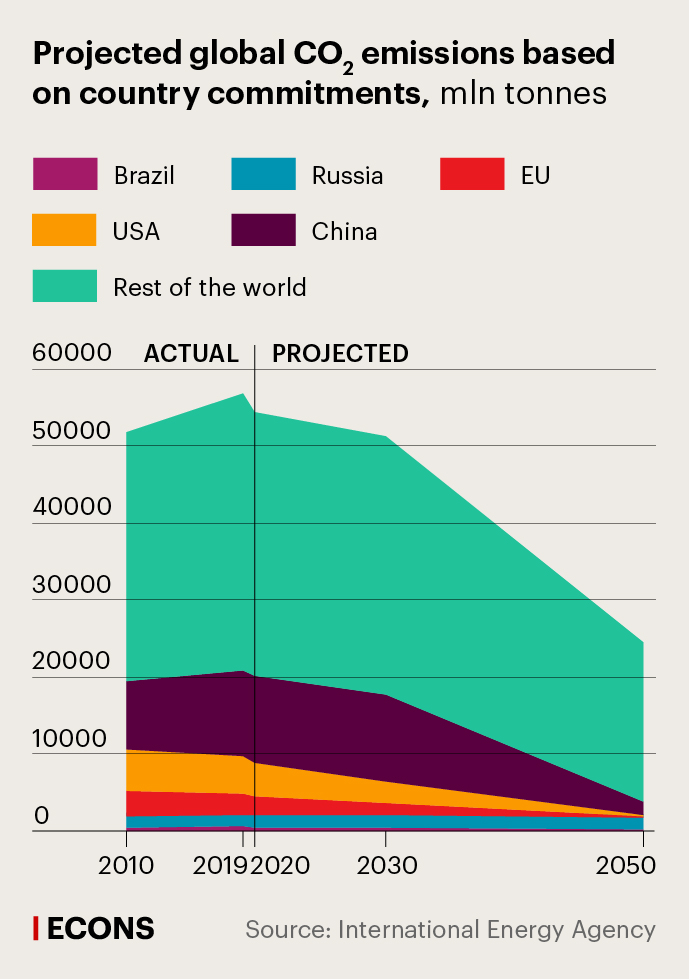

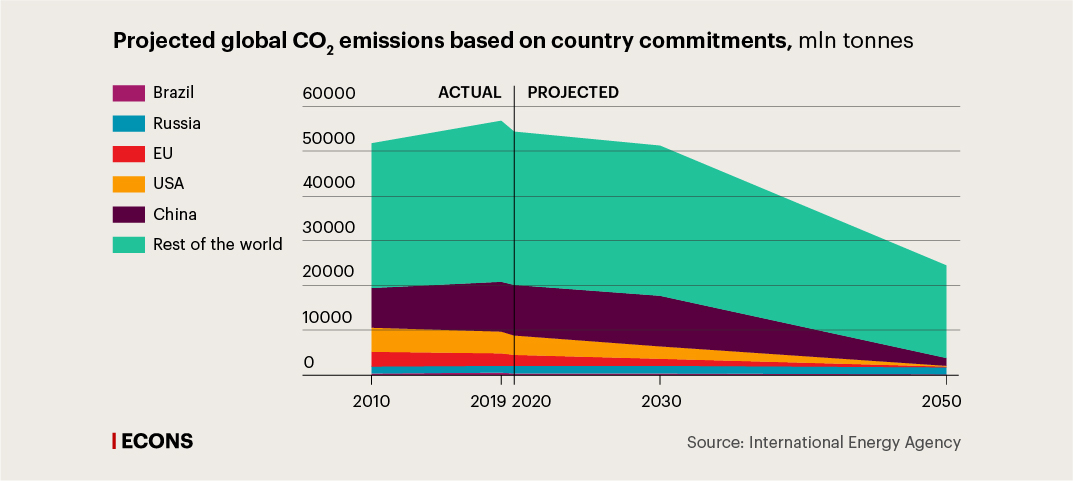

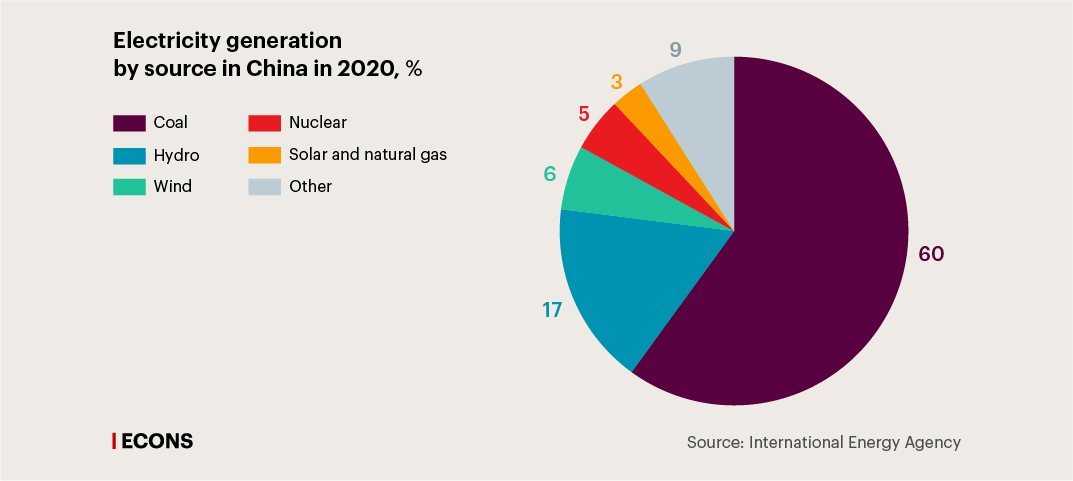

At the same time, the refocus of the Russian economy on Asia does not make the climate transition risks less important for Russia considering that Russia-friendly countries are also setting ambitious carbon neutrality targets. This is clearly evidenced by the co-organiser role of the People’s Bank of China (PBC) in the Green Swan conference. China currently ranks number one in carbon emissions ( 27% of the global amount). Its carbon emissions are projected to peak in 2030, however, the country expects to reach carbon neutrality by 2060. In some issues that stimulate the energy transition, China’s financial authorities are even ahead of the EU.

According to Zhou Xiaochuan, an ex-governor of the People’s Bank of China (PBC) and vice chairman of the Boao Forum for Asia, China will need at least $20 trillion to fund the transition over the next 40 years. This is a huge amount. The government will be able to provide only a small part of this funding. The remaining share should be raised in the equity and bond market, and through bank loans.

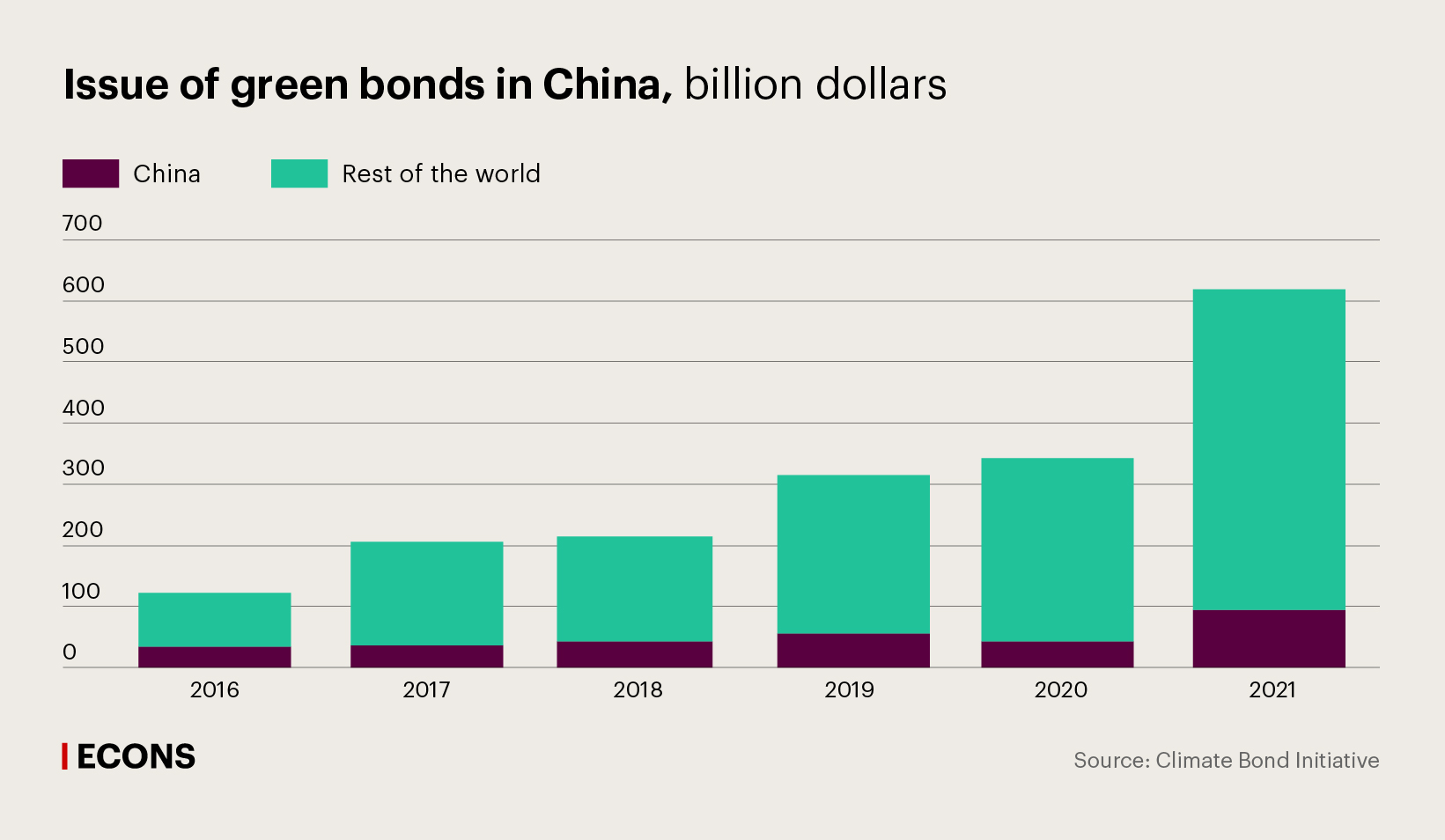

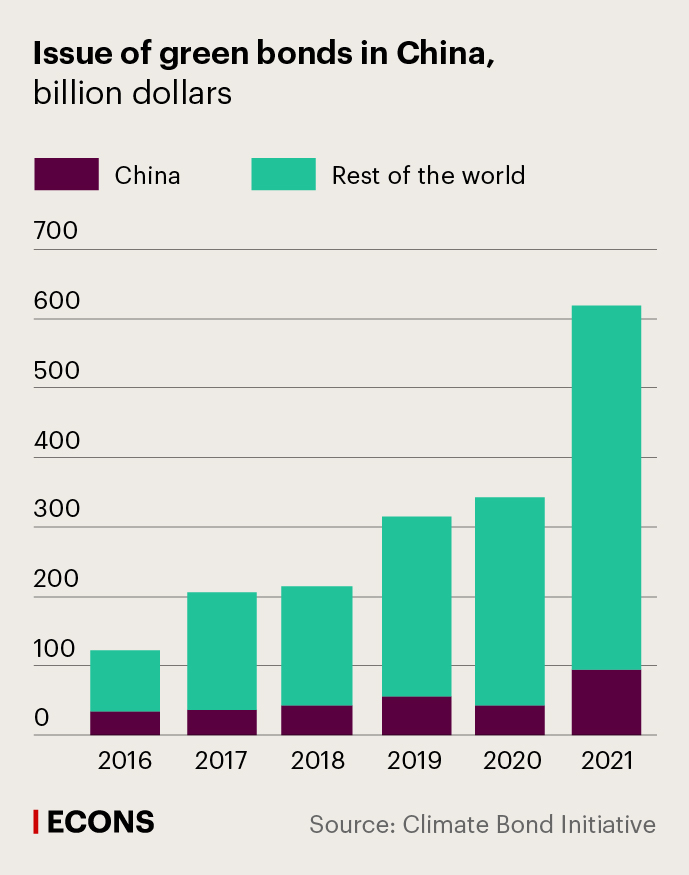

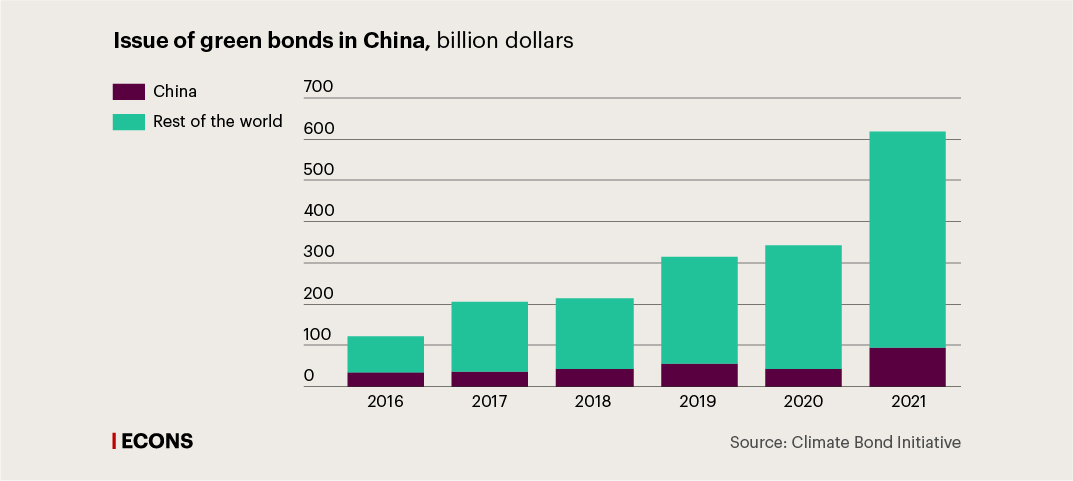

The Chinese market for financing environmental projects is rapidly developing. In March 2022, the issue of green loans exceeded 19 trillion yuan ($2.7 trillion), and the volume of green bonds that entered circulation totalled 1.3 trillion yuan ($200 billion), making this market one of the largest in the world. China’s green and transition financing market is expected to continue apace.

What exactly are the PBC’s and other major central banks’ current activities and plans to foster the energy transition? These activities may be grouped into four key areas: monetary policy, delivering financial stability, taxonomy development and information disclosure, and carbon pricing analysis.

1. Monetary policy

Delivering price stability is a top priority for any central bank. However, some economists admit that assisting the transition to green energy may be a factor for a central bank to reasonably consider as long as this does not run counter to its price stability mandate.

The integration of climate targets into central banks’ market operations may theoretically be accomplished through diverse approaches to green and brown assets when making up a list of eligible collateral assets to secure refinancing operations, asset purchases, and for managing reserves and other asset portfolios. The potential incentive would be targeted programmes of preferential refinancing for banks issuing green loans.

Yet, the vast majority of central banks are in no hurry to make energy transition incentivisation part of their monetary policy toolkit because of significant risks to their core mandate. The two exceptions here are the PBC and the Bank of Japan.

In November 2021, the PBC launched two preferential lending programmes:

- Carbon emission reduction facility: banks may receive funds at a reduced rate to ramp up their lending to emission reduction projects. PBC finances 60% of the amount of loans issued for eligible projects at 1.75% (compared to the PBC current key interest rate of 3.7%).

- Lending to clean coal projects: preferential loans from the PBC are available to banks financing projects aimed at more environmentally friendly use of coal (combustion, production, etc.). The interest rate is also 1.75%, with the volume of PBC lending expanded to cover 100% of loans for clean coal projects. Initial plans envisaged 200 billion yuan (about $30 billion) worth of such preferential loans to be issued, but in May 2022, the amount was raised to 300 billion yuan ($45 billion) in response to growing global energy prices.

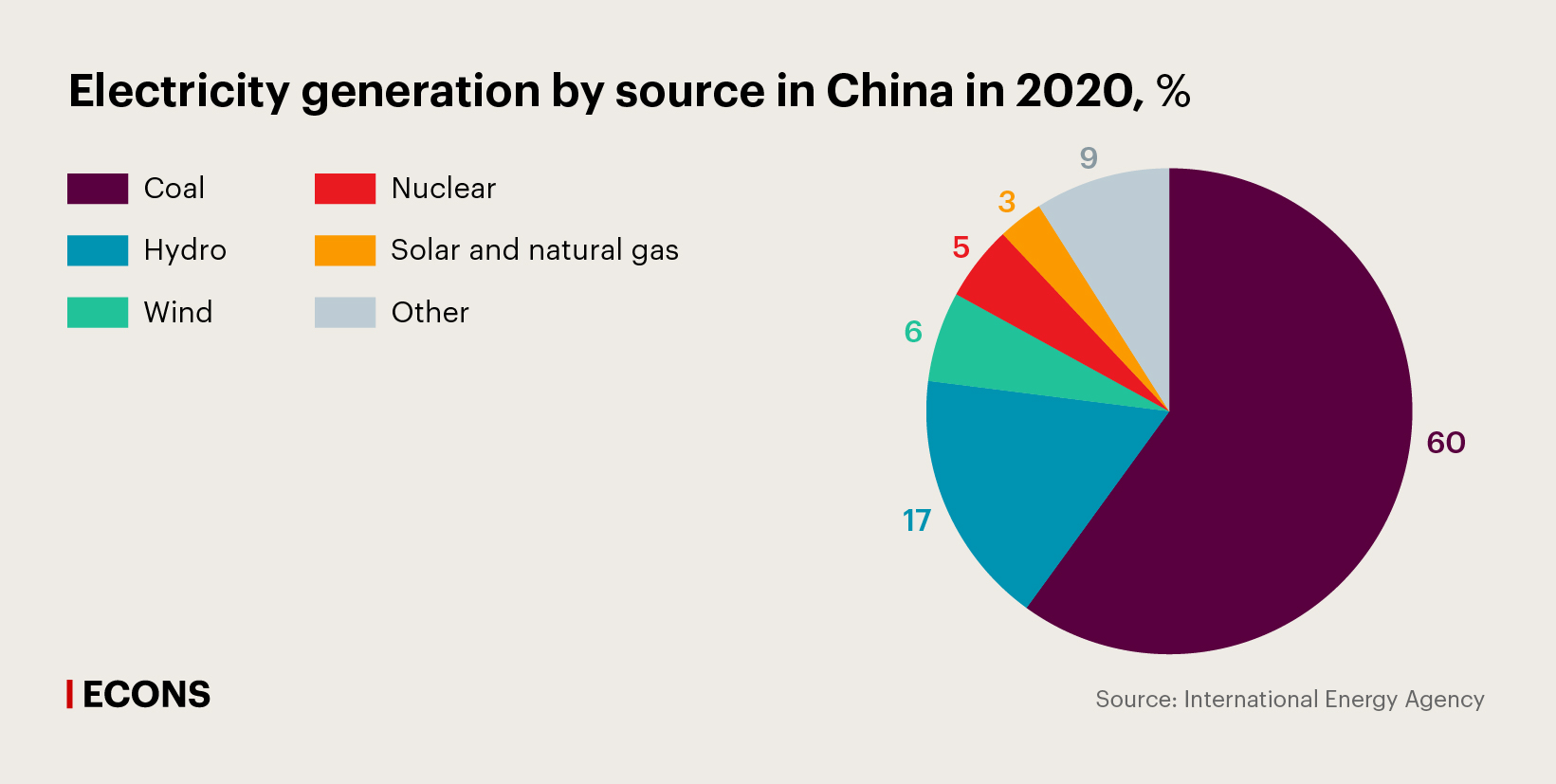

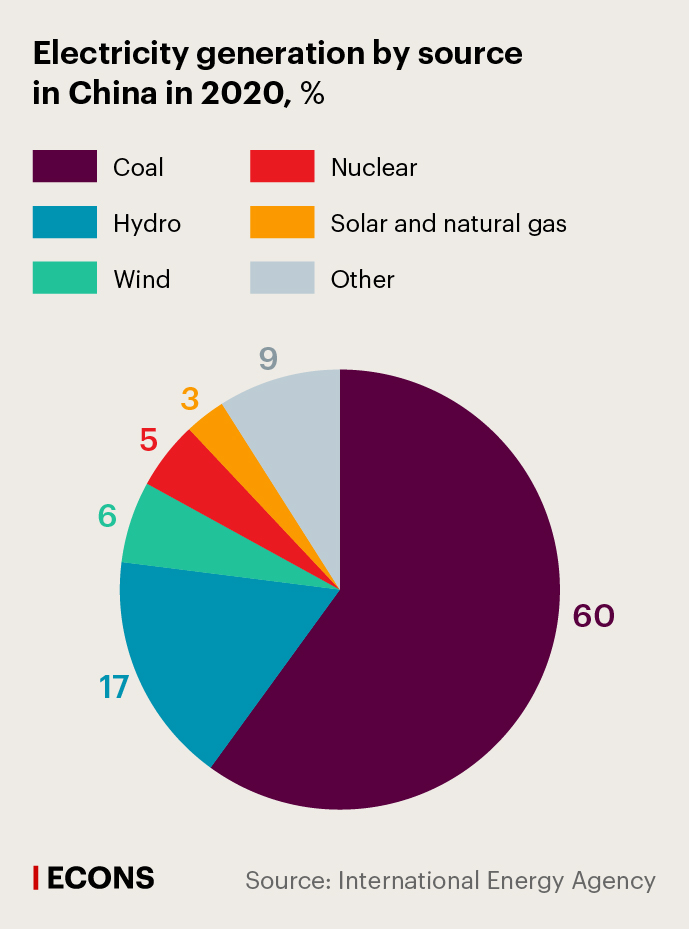

Importantly, the Chinese economy is strongly reliant on coal (China is a global leader in coal mining and use), and cannot wean itself off coal despite the adverse environmental impact.

Chinese authorities take the most realistic approach to the climate transition: there are no plans to abandon traditional sources of energy until an adequate supply of renewables is in place. The strategy is governed by the ’construction before destruction’ principle, as Lyu Zheng, Deputy Secretary General of the PBC’s Monetary Policy Committee said at the conference.

Banks participating in the PBC incentive programmes are required to disclose information quarterly on the progress and accomplishments in emission reduction made thanks to the their loans. As of late May 2022, the PBC allocated 210 billion yuan ($31 billion) worth of concessional financing under its two facilities, delivering an annual reduction in carbon emissions of 60 million tons of CO2 equivalent (about 0.6% of China’s annual emissions).

In December 2021, the Bank of Japan also launched a preferential lending facility for banks focused on the green agenda. Banks that disclose information in accordance with recommendations by the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) set up under the Financial Stability Board (an international organisation established in 2009 to coordinate regulatory and supervisory policies in the financial sector) are entitled to preferential financing at the rate of 0% (vs 0.3% on regular loans) within their investments in green and transition assets.

However, the PBC and the Bank of Japan are the exceptions. These regulators may have rolled out their incentive programmes bearing in mind that unlike most countries, inflation was significantly below target in both China (1.5% vs 3%) and Japan (0.8% vs 2%) in late 2021. The central bank’s mandate is to ensure price stability, while the use of monetary policy for other purposes, such as support for the transition to a low-carbon economy, may bring negative effects on the initial objectives of monetary policy and threaten the independence of central banks. With global inflation rates accelerating to their highest in many years, the central banks in major countries are likely to focus on curbing inflation.

Meanwhile, many central banks already include climate transition forecasting in macroeconomic analysis supporting their monetary policies. This suggests that the carbon neutrality agenda is taken into account in policy rate paths.

2. Ensuring financial stability and stress testing

The energy transition sets the stage for a decline in the share of traditional energy sources and therefore relevant industries (and brown companies generally) are subject to increased credit risks in the long term. But they may also face difficulties in raising finance in the short term as investors are implementing their green strategies. That is why financial regulators are tasked to ensure the appropriate accounting of these risks by banks and other creditors. Regulators solve these problems at the micro and macro levels, and often with the help of stress testing.

In his presentation at the conference, PBC Governor Yi Gang spoke on China’s experience of climate stress testing in the second half of 2021. The stress testing covered 23 major domestic banks and only the three most carbon-intensive industries: thermal power, steel production and cement production. During the stress testing the regulator explored the impact of rising costs due to carbon emissions on the ability of companies to service their debts through 2030, as well as the quality of relevant assets of banks and capital adequacy. Three scenarios (moderately negative, negative and extremely negative) were assigned three carbon price levels based on the changes in the Chinese domestic carbon prices and NGFS scenarios.

The PBC stress testing found that in all scenarios, the aggregate capital adequacy ratio (CAR) of participating banks drops, but not very significantly, from 14.89% to 14.27% in the most negative scenario, and to 14.57% in the moderate scenario. The PBC Governor explained that the result was due to the low share of struggling enterprises in the loan portfolio of respondent banks. Moving forward, there are plans to extend the scope of the stress testing to cover 18 industries including the aviation and chemicals sectors. It is also possible that some of the negative effects would not emerge until 2030, given China’s plans for the most aggressive reduction in emissions after 2030.

3. Taxonomy development and information disclosure

The PBC’s key difficulty in holding the stress testing was the lack of data and inadequate carbon emission disclosures, said Mr. Yi Gang. China will therefore phase in the requirements for mandatory environmental risk disclosure by all financial institutions as part of a uniform standard. China and the EU confirmed their plans to comply with internationally agreed standards being developed by the IFRS Foundation (its first version was published in March 2022, with the consultation period open through end of July 2022). The United States, which does not use IFRS, plans to rely on its own climate change disclosure standards (their first version was published by the SEC in March 2022).

Some difficulties originate from the lack of a single global taxonomy of green projects. China was one of the first countries to develop its own taxonomy (2015), followed by the EU (2020). In 2020-2021, an EU and China working group compared the two taxonomies and concluded that they were substantially the same.

What matters most is not only the definition of green projects, but also the assessment of a wider range of transition projects, including those implemented by companies, that cannot be classified as green. To differentiate projects aimed at facilitating the transition to a low-carbon economy from those focused on transition washing and useless in terms of carbon neutrality goals, it is necessary to develop a clear taxonomy of transition financing. This taxonomy will help investors reduce the cost of searching for information and boost the credibility of green projects.

The EU has come up with proposals to expand the taxonomy to transition projects. The PBC is also working to create a taxonomy of transition financing for the four most carbon-intensive sectors: thermal power, steel production, cement production and agriculture. China’s taxonomy will include clear transition plans for carbon-intensive industries based on guidelines from relevant ministries.

4. Carbon credit markets

The traditional role of central banks is developing financial markets and fostering price setting. From the climate transition perspective, it is essential to set carbon pricing and ensure the interconnection between carbon markets (for example, the carbon allowance market and the carbon offset market, which would ensure consistent operation of incentives and constraints – see the box).

July 2021 was marked by the launch of a national emission trading system (ETS) in China after the country had pilot-tested several regional emissions trading systems for a few years. At this juncture, the system is limited to one sector – electricity generation. However, the sector accounts for 40% of all China’s CO2 emissions. Over 2,000 power plants with annual emissions above 26,000 tonnes of CO2 equivalent participate in the ETS. There are plans in China to gradually expand the sectoral coverage of the ETS as part of the next five-year economic development plan (2021–2025) and include in its scope the production of steel, non-ferrous metals and cement.

In summary, with regard to the relevance of the green agenda for central banks, the following conclusions can be highlighted:

- The current upturn in commodity prices combined with highest global inflation in many years are set to have a negative impact on prospects for the global transition to a low-carbon economy.

- The transition to a low-carbon economy is a priority for China. In our view, China’s construction before destruction approach appears to be viable and more cost efficient than the EU approach, whose main focus is to stop buying Russian fuels.

- In the long term, the high energy prices will create further incentives to the transition to green energy sources.

- The transition to a low-carbon economy is a joint effort of the private sector, the government and the financial regulator. In addition to their key goals (supporting price and financial stability) central banks seek to facilitate structural transformation in the economy. Their key tasks are to facilitate the development of market tools to finance the green transition, improve information disclosure, monitor the risks of financial institutions, and develop carbon credit markets. The Bank of Russia will also continue its active efforts in this area.