What is open to the Bank of Russia, while remaining closed for analysts?

‘It seems obvious that the Central Bank had in store information that the market lacked. Can you tell us what is that you know that the market does not know?’ one of the journalists asked (link in Russian) Bank of Russia Governor Elvira Nabiullina at the press conference on 22 July 2022, when the Bank of Russia lowered the key rate by 150 basis points at a time compared to the expected 50–75 bp cut. This is exactly the question that has been worrying journalists and the expert community for years: why is the Bank of Russia so unpredictable? Moreover, why has the launch of publications regarding the key rate path failed to improve the predictability of its decisions? We did try to address these questions in our new research.

Predictably Unpredictable

The subject of poor predictability of the Russian Central Bank’s decisions has haunted mass media and analysts’ publications to such an extent that analysts have wittily named the Bank of Russia ‘predictably unpredictable’ (Shal A. Russia's CBR: Predictably unpredictable. J.P. Morgan Economic Research Note, May 28, 2021).

The predictability of the Bank of Russia’s decisions got an extensive discussion in 2018 after the publication of the IMF report, where the Central Bank of the Russian Federation was referred to as the most unpredictable central bank in the world. According to the report, over the period from 2010 to 2018, 27% of key rate decisions were not expected by the market. Meanwhile, the unpredictability of decisions made by the central banks of other emerging market economies turned out to be appreciably lower: 19% for Brazil, 13% for Turkey and India, and 9% for Thailand. In contrast, central banks in advanced economies were typically very predictable. For example, according to Bloomberg consensus data, none of the moves by the US Fed came as a surprise over the same period.

The subject was further developed by analysts Alex Isakov et al. in their paper, which also presented data on the proportion of the key rate decisions correctly predicted by the market over the period from 2015 to 2018, i.e. the inflation targeting period. During these years, the average unpredictability was 35% compared to 10% for New Zealand (this country had been selected as the benchmark due to its successful experience in publishing the future policy rate path, which was exactly the main recommendation of Isakov’s paper with regard to improving the Bank of Russia’s communication).

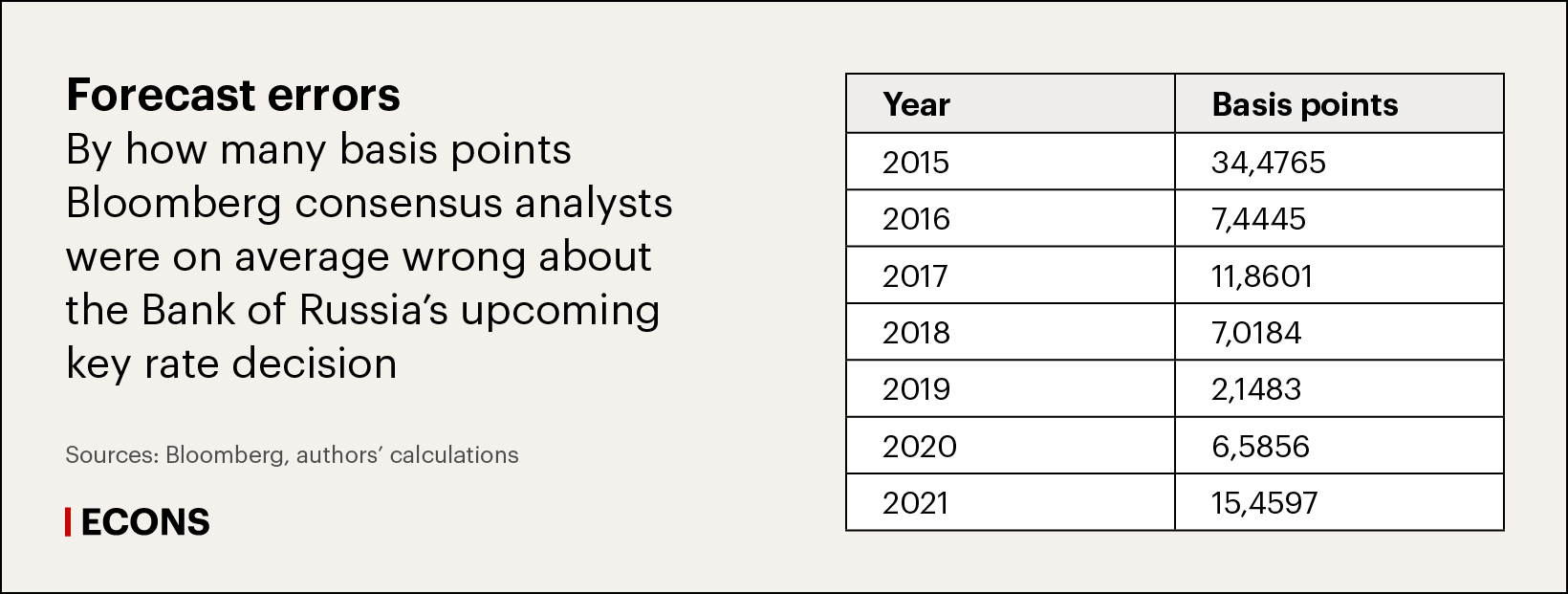

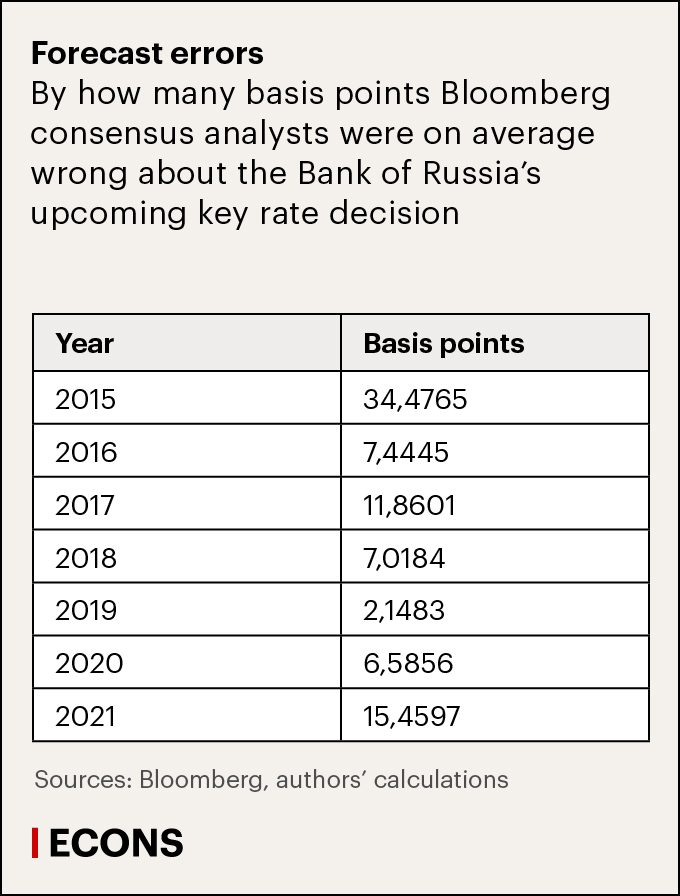

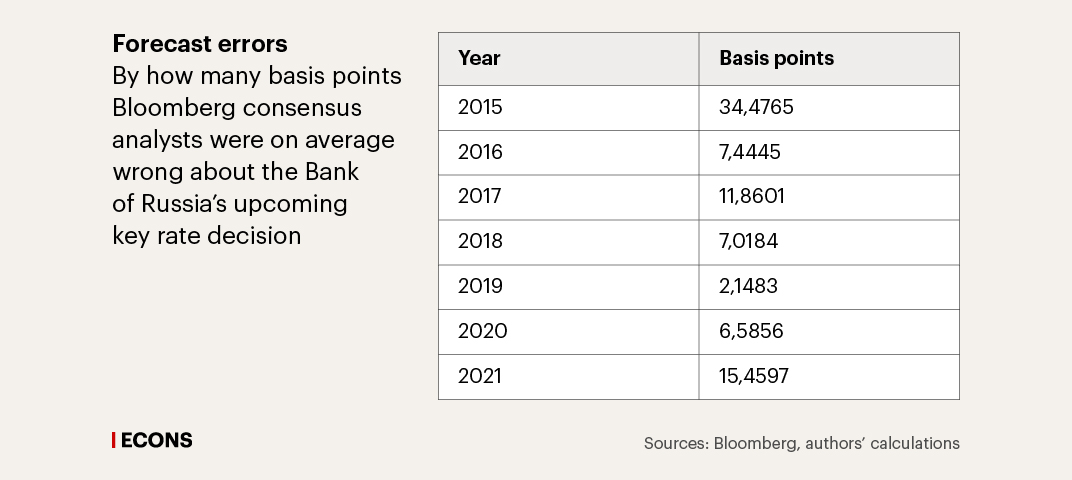

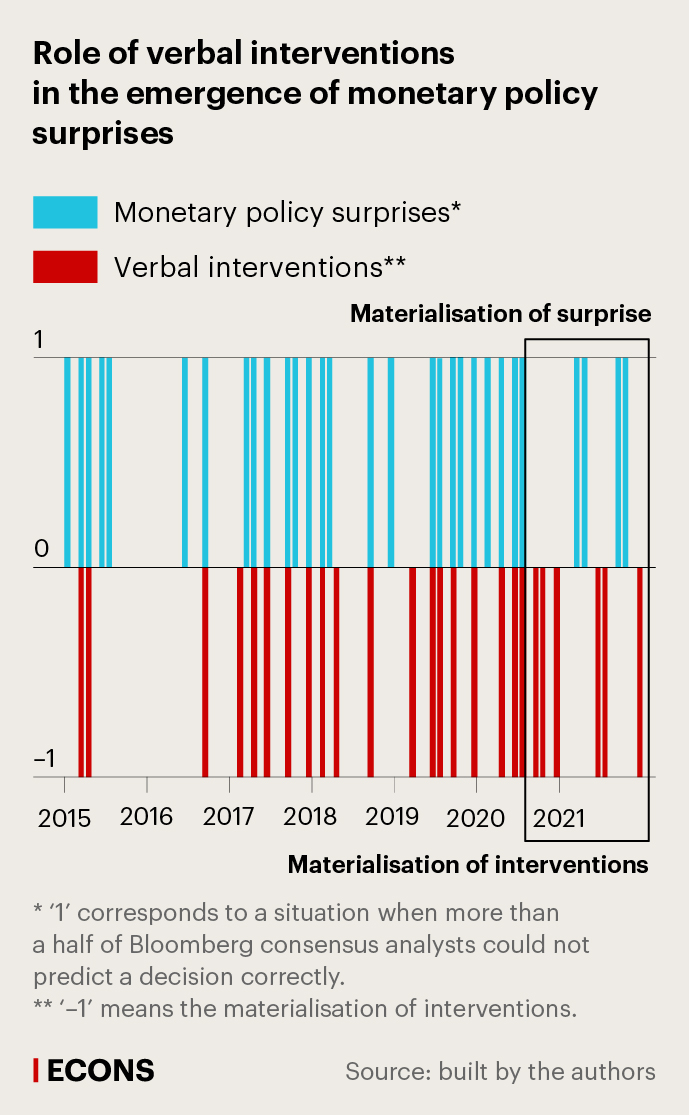

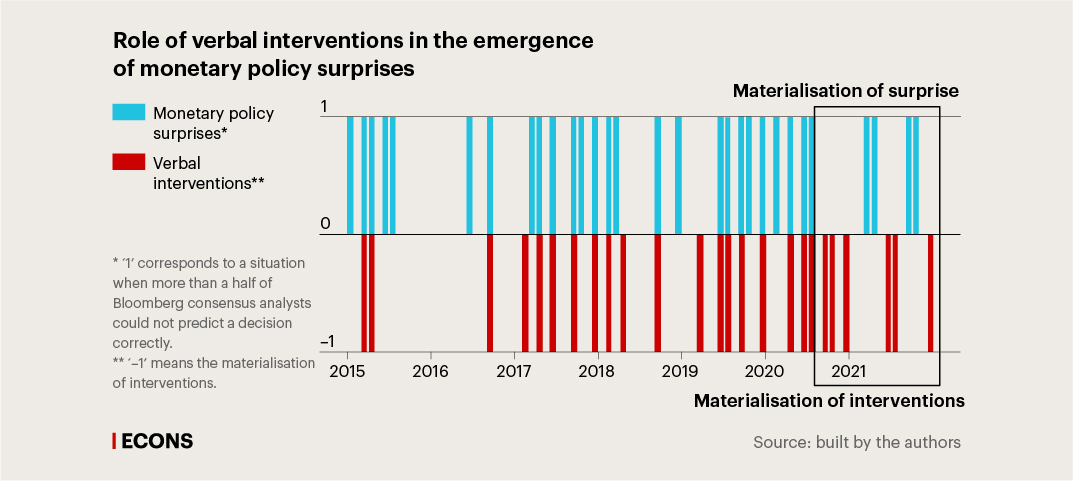

In April 2021, the Bank of Russia began to publish a forecast path of the key rate. However, counter to expectations, the predictability of the Bank of Russia’s decisions has deteriorated since that time rather than improved. In the period 2015–2021, on average, analysts were wrong by 12.14 basis points in their forecasts of Bank of Russia decisions, including by 15.46 bp in 2021 alone.

However, analysts are wrong by far more when the Bank of Russia changes its key rate (the error is 17.06 bp on average), and they are wrong much less when the key rate remains unchanged (by 5.09 bp on average). In other words, it seems to be relatively easy for them to predict the future direction of key rate changes but rather more difficult the specific step of such a change.

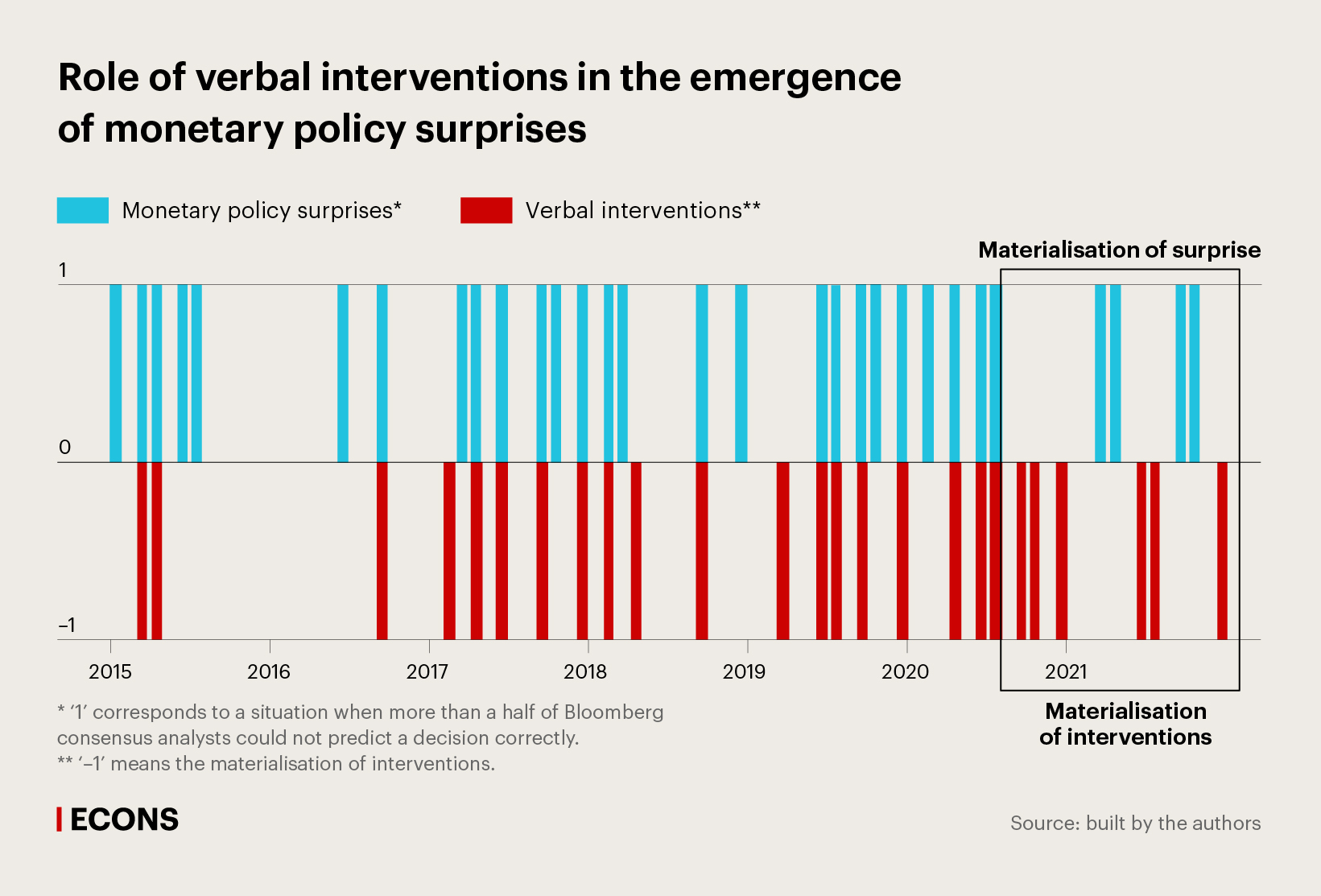

Concurrently, we found out that starting from 2021, analysts have been virtually never wrong when key rate decisions were preceded by verbal interventions by the Central Bank’s representatives (interviews, comments, articles, columns etc., published two or three weeks ahead of key rate meetings).

Following the transition to the inflation targeting regime in 2014, the Bank of Russia has gradually expanded its communication tools, with its decisions to publish

the key rate path and

the Model Framework section of the website (link in Russian) made in 2020 and 2021. The market needed some time to learn to understand the signals of the regulator. The publication of the key rate path could have a positive influence on the predictability of decisions by improving the process of verbal interventions.

Nevertheless, the paradoxical increase in the number of errors in analysts’ forecasts following the publication of the key rate path launched by the Bank of Russia posed a research challenge: what could trigger the emergence of surprises (link in Russian) of the Bank of Russia’s monetary policy, i.e. decisions that were not expected by the market?

Source of surprises

The research literature offers several popular approaches to answering the question about the origin of monetary policy surprises. They may emerge in the following cases:

-

Amid elevated macroeconomic uncertainty. When inflation has to be managed in rough times, there may simply be not enough time to provide explanations and communicate future decisions.

-

Amid the so-called persistent miscommunication (or misunderstanding). It happens when a central bank does not voice its real view, thereby misleading the market. Or when emphasis is misdirected. Or when the market cannot interpret correctly the signals of the central bank.

-

Amid information asymmetries, in case of the central bank’s information advantage.

Our special focus is now on the third point – an information advantage. This is an objective (true) or subjective (backed solely by the market’s confidence) possession by the central bank of more advanced analytical and/or model frameworks which help it to make better forecasts of future developments in the economy. Thanks to this advantage, the central bank can come up with decisions which are quite unexpected by the market, as the latter simply does not possess such advanced tools.

The main work on information advantage is believed to be the paper by Christina Romer and David Romer from the University of California, Berkeley, published in 2000 in the American Economic Review, a reputable research journal. The authors study the Federal Reserve’s information advantage and the impact of monetary policy decisions on forecasts made by market analysts. Based on their research, the authors conclude that in 1970–1991, the US Fed possessed an information advantage when preparing inflation and GDP forecasts with horizons of up to six quarters.

Drawing on this paper and the recent study of the role of the information channel in monetary policy conducted by experts from Pompeu Fabra University and the San Francisco Fed, we conducted two tests.

First, we checked who predicts inflation better – market analysts or the Central Bank. Second, we studied factors influencing the adjustment of inflation forecasts by analysts during one week following a key rate decision. If the Central Bank does not have an information advantage, then either there will be no adjustment at all (as the market has already factored in the expected decision in its forecast), or it will be opposite to the decision made, i.e. when the key rate is raised, analysts should move their inflation forecasts downwards (in anticipation of lower inflation due to tighter monetary policy), and when the key rate is cut, they should move their forecasts upwards (expecting a pickup in inflation due to monetary policy easing).

Finally, we obtained the following results. Over the entire period under consideration (2015–2021), the Bank of Russia had an information advantage when forecasting inflation over the horizon of up to three subsequent quarters. In this situation, analysts typically raised their inflation forecasts when the key rate was up and lowered them when the key rate was cut. The expert consensus moved counter-intuitively. In other words, the market behaviour was governed by the following logic: if the Central Bank increased the key rate, it meant that in its opinion inflation risks were higher than in ours, therefore the inflation forecast had to be raised. On the other hand, vice versa, if the Central Bank lowered the key rate, it meant that it viewed risks to be much more serious for the economy, compared to us; therefore the inflation forecast had to be lowered.

There is an important detail: such a shift in forecasts is typical for a short-term horizon. Over a mid-term horizon, the market was generally sure that inflation would reach the 4% target.

We believe that in order to counter the information advantage, it is essential to disclose all elements helping the transformation of statistics into a key rate decision. These represent model and analytical frameworks (including the code of forecasting models) underlying the forecast and Taylor’s rule, which is the monetary policy rule determining the consistency between the nominal interest rate and key macroeconomic parameters.

It is not enough for the market to see key rate steps in the final forecast, it is important to know how they have been derived. Economists are well aware of the fact that similar data are used to build different models. The authors of the aforementioned research about the role of the information channel mention the publication of the Minutes, the protocol of the meeting on the rate level, as one of the success factors that helped the US Fed to cope with the information advantage.

What Other Factors May Reduce Predictability

We also tested two other hypotheses: about the high role of uncertainty and about miscommunication. First of all, both of these factors do not influence materially the emergence of monetary policy surprises. However, we were able to find certain nuances of the Bank of Russia’s outreach that could improve predictability.

To test the impact of uncertainty and information shocks, we used approaches described in the recent literature (e.g., here, here, here, and here). We measured uncertainty as the variance of analysts’ forecasts (assuming that high uncertainty leads to a wider spread in forecast numbers) and as the news index which was built using big data and textual analysis. Neither of the variables make a meaningful contribution to the emergence of monetary policy surprises. In other words, it is similarly difficult for analysts to predict the Central Bank’s actions in both rough and quiet times.

To test the impact of miscommunication, we relied on the method

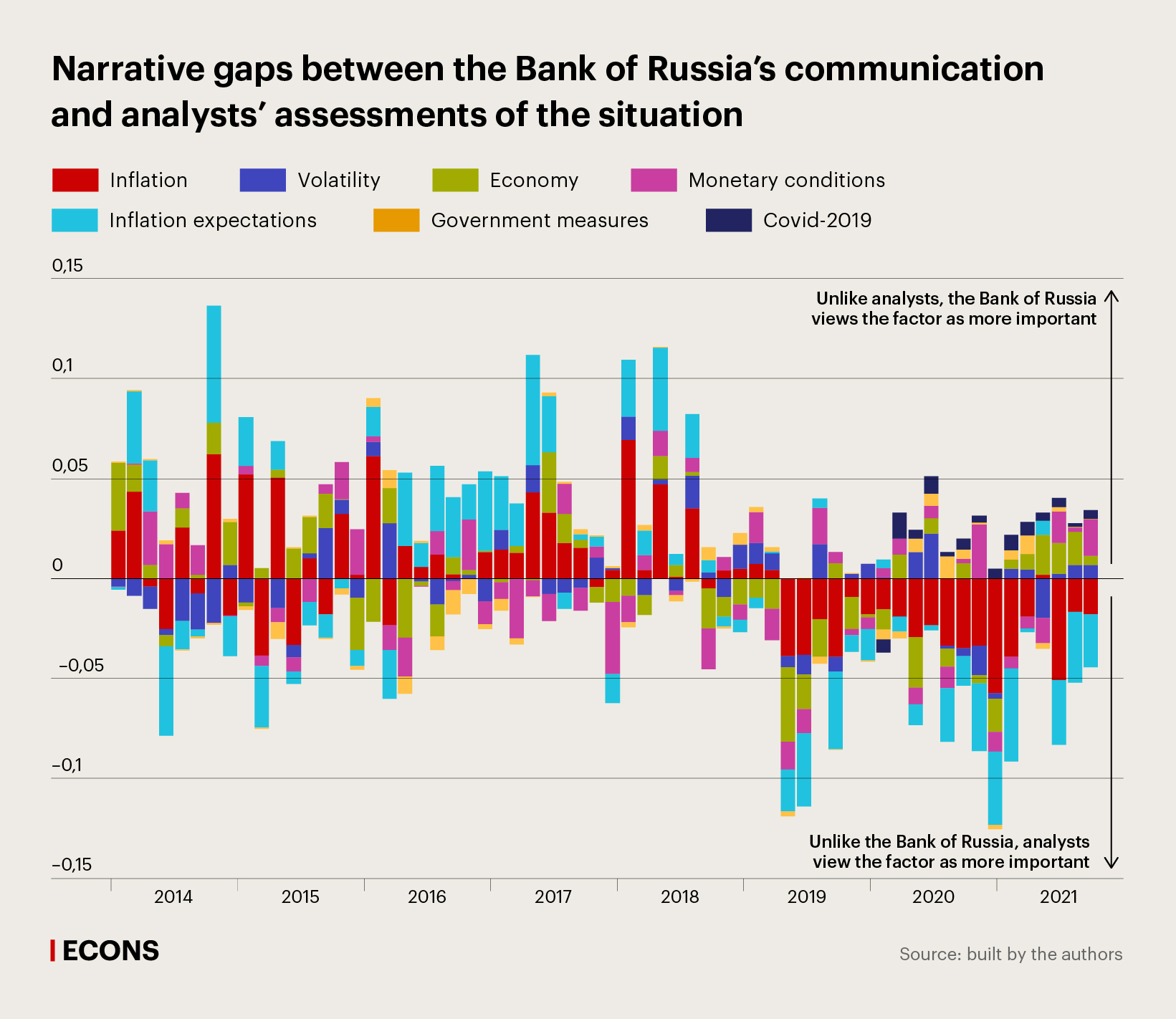

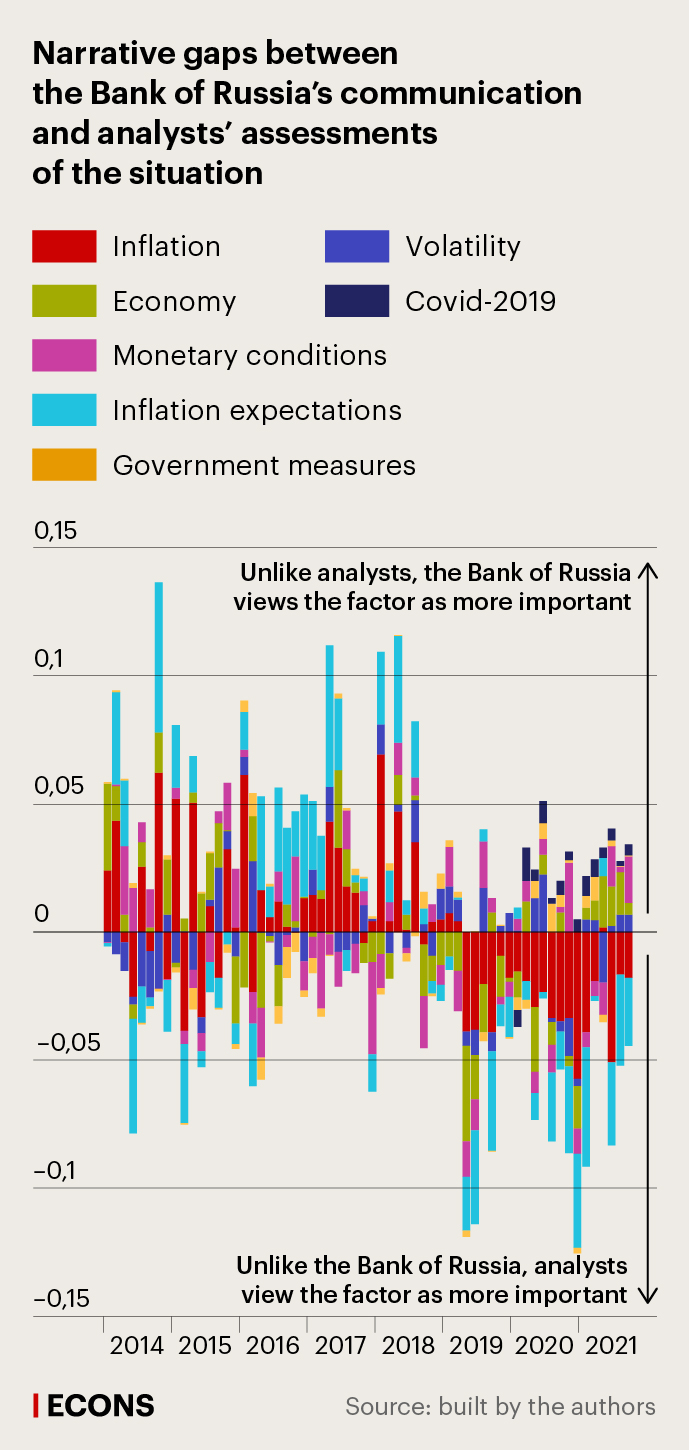

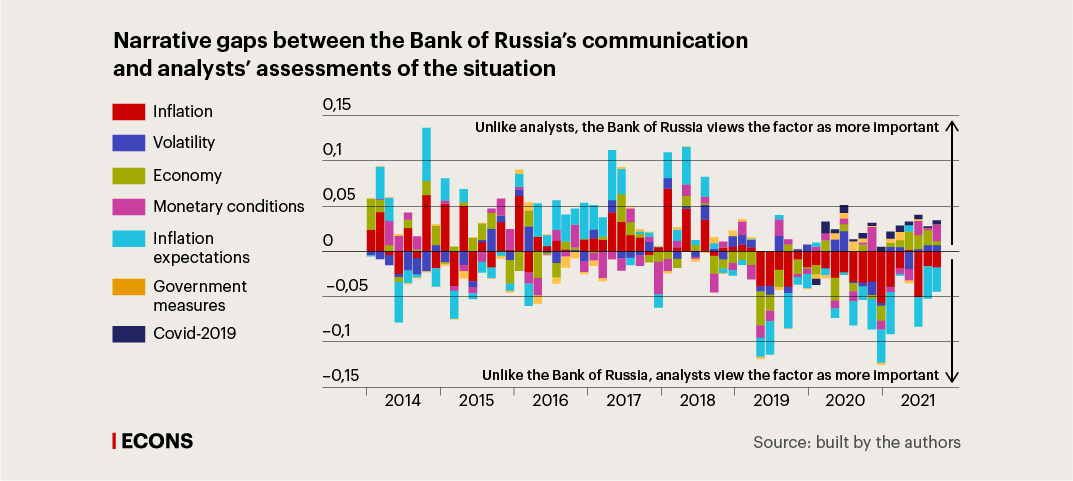

used by experts from the Bank of Norway. We compared two corpora of texts as input data: professional analysts’ reviews made before key rate decisions (where analysts put themselves in the place of the Central Bank and tried to guess the future decision based on available public information) and key rate communication (the press release and the Governor’s statement). With the help of guided LDA (Latent Dirichlet Allocation), a thematic modelling method, we derived several main topics (inflation, volatility, economy, monetary conditions, inflation expectations, government measures, and COVID-19) and compared their frequency in both corpora. Then, we assessed narrative gaps, an indicator reflecting a difference between the frequency with which analysts mention each topic and the frequency with which the Central Bank mentions the same topics. In the absence of miscommunication, the narrative gap should approach zero. This corresponds to the ideal situation, when the rationale behind the decision announced by the Central Bank exactly corresponds to the one embedded in market expectations.

It follows from the above chart that narrative gaps between the Bank of Russia’s communication and analysts’ expectations are rather substantial. However, they may be both associated with the fact that analysts and the Bank of Russia perceive the economic situation differently and, largely, determined by the specific structure of Bank of Russia publications. For example, press releases on the key rate always include a paragraph about the economy, whereas analysts’ reviews are more situational.

There is another important observation: before 2019 the Bank of Russia always attached more importance to inflation expectations and inflation in its communication than the analysts, who subsequently also began to pay far more attention to these indicators, devoting their pre-decision research notes to these topics. This steady attention paid by analysts to inflation virtually coincides with the ‘anchoring’ of their inflation expectations to the 4% target.

The ultimate conclusion of our research is that of the three main causes of monetary policy surprises, namely situational uncertainty, miscommunication and information advantage, the unpredictability of the Bank of Russia’s decisions is largely associated with the latter factor. This means that, in the market’s opinion, the Central Bank has certain non-public information and/or possesses more advanced forecasting methods. The experience of other central banks shows that with the development of communication as an inflation targeting tool, their information advantage is waning. Its existence at the present moment is a characteristic sign of the emergence of the inflation targeting regime in Russia and the development of communication as its tool.

.jpeg)