Can We Presume That Inflation Expectations Are Anchored in Russia?

As the critical factor for the central bank to ensure price stability, inflation expectations determine inflation trajectory. Recent studies indicate that inflation expectations appreciably influence savings and consumption decisions and the choice of financial instruments. Businesses plan investments, salaries, recruitment plans, and prices based on their inflation expectations. The inflation expectations of banks influence the level of interest rates on loans and deposits, and the inflation expectations of public authorities determine indexation policies.

The consideration of inflation expectations in the process of developing and implementing monetary policy is the most important change in the understanding of how monetary policy should be implemented in the past 100 years. Its significance may be comparable to the appearance of macroeconomics as an independent scientific discipline and a guide for action in the 1930s.

The experience of the most successful central banks targeting inflation suggests that inflation expectations must be anchored, that is, they must be stable and ‘tied’ to the central bank’s inflation target. When this is the case and there is a temporary pickup in inflation, economic agents are confident about a subsequent slowdown in price growth and a return to the inflation target. As a result, the short-term inflation spike dissipates, and no additional monetary policy tightening is required. Thus, anchored inflation expectations make it possible for the central bank to stabilise both inflation and the economy, gaining more freedom to conduct countercyclical policy to smooth the economic cycle, i.e., to mitigate the adverse effects of booms and busts by changing the key rate, or, in other words, to engage in ‘flexible inflation targeting’.

How can inflation expectations be anchored? Judging from international experience, the key factors include trust in monetary policy (this arises when the announcements of the central bank do not contradict its real actions), experience in keeping inflation close to the stated target, and the financial literacy of economic agents (meaning their ability to plan their own financial decisions and their interest in doing so).

Since 2015, the Bank of Russia has been implementing its monetary policy in line with an inflation targeting regime, seeking to maintain annual inflation close to 4%. Has the nature of inflation expectations changed since then? Have we managed to anchor them? What prevents their anchoring in Russia? We consider these and other issues in an analytical note published on the Bank of Russia website (link in Russian).

The document looks into changes in the inflation expectations of households and analysts (professional economists engaged in inflation forecasting). Other central banks mainly pay attention to the inflation expectations of analysts and financial markets, viewing them as more informative. These represent the expectations of agents who are interested in better inflation forecasts, who possess the necessary skills, and, ultimately, who vote with their money.

International experience indicates that the inflation expectations of households and businesses are less important for monetary policy:

-

Households and businesses are not incentivised to make highly accurate inflation forecasts (for households, changes in the cost of living, such as wage indexation and prices for marker commodities (link in Russian) are of more importance, while for businesses, pricing factors in the markets where they sell products, buy equipment and components, and hire staff are more important).

-

They do not have sufficient competence to forecast inflation (in particular, businesses mainly focus on market researchers, rather than analysts forecasting the CPI).

-

Households’ and businesses’ expectations do not always materialise in their economic decisions. Household inflation expectations may reflect a degree of concern about rising prices, rather than a desire to act, while businesses’ decisions on the levels of selling prices are limited by contractual terms, demand, and market competition. According to the survey of businesses (link in Russian) commissioned by the Bank of Russia, only 23% of respondents noted that their inflation forecasts often influence their pricing policy, and only 18% spoke about an impact on investment.

However, households’ perceptions of expected price changes are, in one way or another, reflected in their own financial decisions regarding consumption or savings. For example, households’ and businesses’ inflation expectations become much more informative in periods of sharp surges of inflation or during crises in general. Therefore, the central bank should seek to gradually anchor inflation expectations by accumulating long experience in maintaining inflation close to the target and by pursuing information policy.

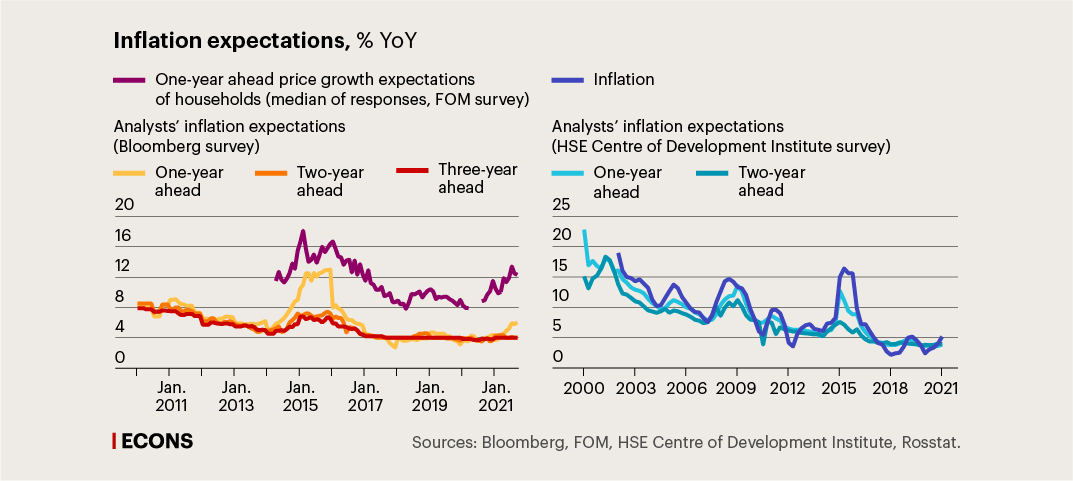

We have studied the anchoring of the inflation expectations of households and analysts using ‘non-structured’ methods, which are methods of assessment allowing the examination of individual economic effects or their totality, and which do not involve the construction of a model of the entire economy. Households’ inflation expectations are derived from the data of surveys by FOM (direct estimates and the balance of responses) and Rosstat, while analysts’ expectations are assumed to be their inflation forecasts collected by Bloomberg and the HSE Centre of Development Institute.

The calculations show that analysts’ inflation expectations have been anchored since the inflation target was reached in 2017. Over this period, they have been close to the 4% target and insensitive to short-term inflation factors.

In contrast, households’ inflation expectations have been unanchored throughout the entire period of the survey. Their movements have been shaped by the prices of marker commodities, most of all of medical and fast-moving goods, as well as certain economic and social events, which did not actually involve any meaningful consequences for prices. Households’ inflation expectations continue to be highly dependent on current inflation and the ruble exchange rate (in crisis episodes). For example, in 2016–2018, households’ expectations abated on the back of slowing inflation, while the indicators of anchoring did not improve. Therefore, such changes cannot be interpreted as a shift towards anchoring.

In general, we believe that the Bank of Russia’s experience in inflation targeting points to considerable progress in anchoring inflation expectations. However, households’ expectations continue to be unanchored, while the risks of inflation expectations becoming unanchored among other economic agents remain.

The anchoring of inflation expectations achieved so far makes it possible to pursue countercyclical monetary policy only to a limited extent. In these conditions, it is important to keep the targets and general approaches to conducting monetary policy unchanged, while improving it and responding promptly to emerging challenges.