Three Challenges for Monetary Policy

During the COVID-19 pandemic and in the post-pandemic period, most central banks faced a surge in inflation. It reached multi-year highs, significantly surpassing target levels in the countries that implement inflation targeting policy. Although inflation in developed economies has since declined, the question as to whether this decrease is sustainable remains a subject of debate (link in Russian). Central banks need to determine how tight their monetary policy should be and how long they should maintain it in order to bring inflation back to the target. This issue is also of particular relevance to Russia.

In the current environment, the answer depends on a number of factors and specific features of the economic situation, both domestic and global, which constitute challenges for monetary policy. These factors can be summarised as follows.

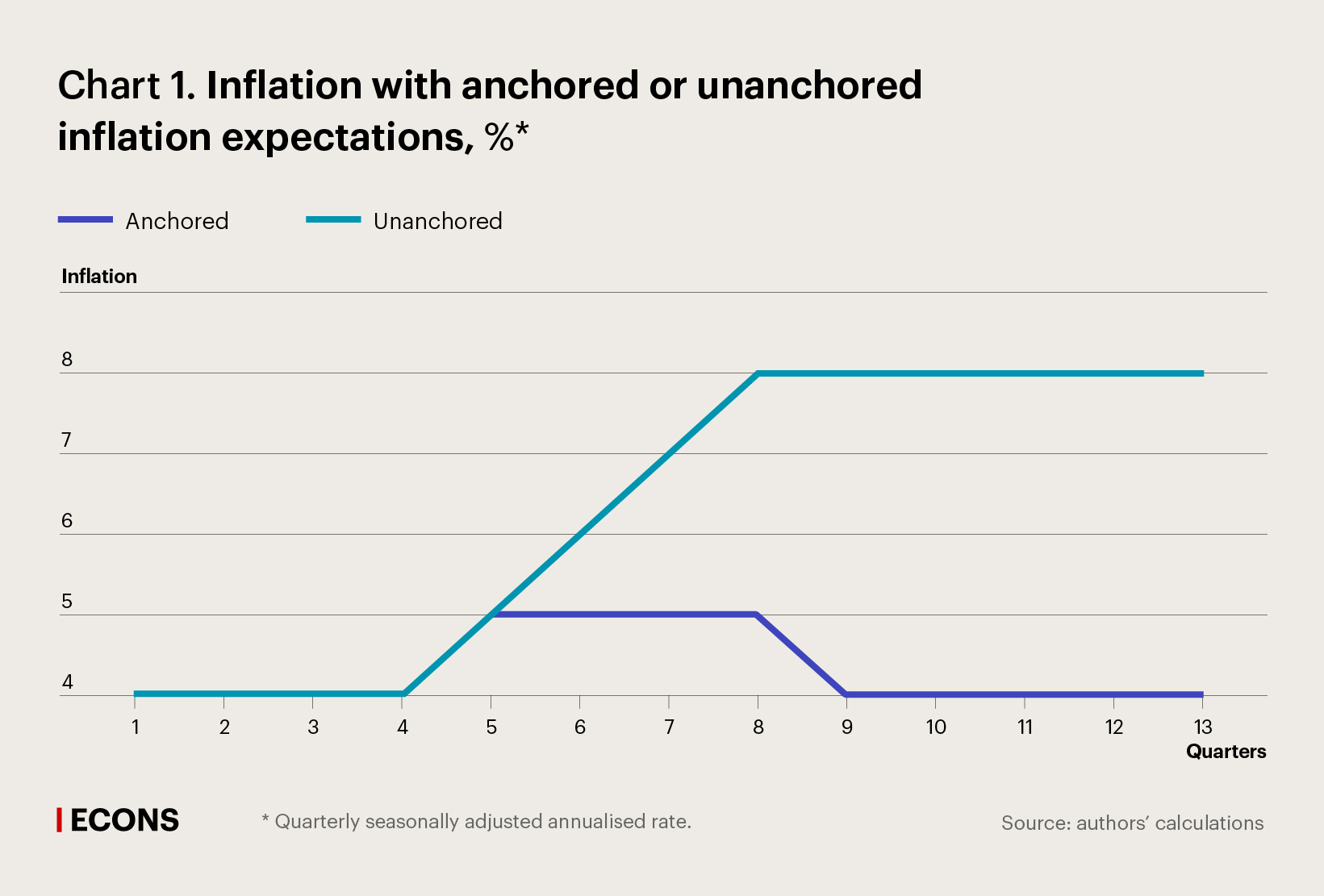

- First, there is a question of whether inflation expectations are anchored at a low level or unanchored. When they are unanchored, which is typical of most emerging market economies, monetary policy should be more ‘persistent’ in order to ensure sustainable disinflation and prevent a considerable resurgence in inflation.

- Second, the non-linear nature of the statistical relationship (the Phillips curve, link in Russian) between the level of economic activity (or unemployment) and growth of prices (or wages). This relationship suggests that high unemployment coincides with low inflation and vice versa, which makes it possible to stimulate demand amid low economic activity at the cost of a slight increase in inflation. However, non-linearity implies that, depending on the stage of the economic cycle, changes in demand will have a stronger impact either on economic activity or on inflation.

- Third, there is an issue of supply shocks, that is, abrupt changes in the volumes of certain goods and services (typically, a contraction) or in the costs associated with their production and transportation (typically, a rise). Depending on a number of factors, monetary policy should take these shocks into account in different ways. The 2020s have generated (and continue to generate) an abundance of pro-inflationary supply shocks of various natures, durations, and intensities. For this reason, the need for monetary policy to adequately factor in these shocks has become another pressing topic of discussion.

Let us now elaborate on each of these points.

Challenge 1: Unanchored inflation expectations

Inflation expectations are considered anchored when they are: 1) close to the central bank’s inflation target and 2) weakly respond to temporary surges in price growth (specifically, to those supply shocks). Whether inflation expectations are anchored or not is directly related to monetary policy.

If they are anchored, monetary policy can largely ‘overlook’ a temporary acceleration of price growth caused by one-off factors. Indeed, once their influence subsides, price growth will revert to its previous trend, without an increase in inflation inertia. In such a scenario, monetary policy responds only to the so-called second-round effects of one-off factors, that is, to a possible rise in short-term inflation expectations as the price shock spreads across the wider economy, but with lower intensity.

For example, an increase in import tariffs for certain goods leads to an upswing in their prices. However, a year later, with tariffs staying the same and the exchange rate remaining stable, this rise will no longer be contributing to inflation, which, all else being equal, will slow down to the level observed before the tariff increase. Nevertheless, if tariffs are raised for intermediate goods used in the production of other items, their growth will, to a certain extent, influence prices along the entire production chain. This will generate a prolonged price impulse and potentially lead to higher inflation expectations. Monetary policy must respond to these effects if they become persistent. However, this is unlikely if inflation expectations are anchored.

Anchored inflation expectations allow monetary authorities to respond more flexibly, including to pursue countercyclical policy, i.e. to be guided primarily by the stage of the business cycle rather than by price dynamics. This is important because price spikes triggered by one-off factors can occur during a recession, which typically requires accommodative monetary policy.

When unanchored, long-term inflation expectations will rise in response to even relatively minor (and seemingly temporary) increases in prices for individual goods and services, and they will do so persistently.

This scenario requires a full-scale monetary policy response as rising inflation expectations lead to automatic easing of monetary conditions – even if interest rates do not decline, because households and businesses start to perceive the current level of interest rates in real terms (that is, net of future inflation) as lower than before. This encourages them to take out more loans and save less, which results in higher demand and debt burden but lower savings for the future, thus further contributing to persistent inflation, which again raises inflation expectations and creates a self-reinforcing spiral. Such a scenario might unfold if the central bank underestimates this mechanism of unanchored inflation expectations in its monetary policy decisions.

It is important to note that from households’ and companies’ perspective, this behaviour is completely rational. Every time inflation hits higher than the central bank’s target, it reinforces households’ and businesses’ confidence that their high inflation expectations reflect the reality better than the central bank’s unfulfilled promises to return inflation to a low level.

In order to return inflation expectations to their initial low levels and stabilise inflation at the target over the medium-term horizon, there should be a temporary negative output gap – a situation where demand is slightly below its potential and price growth remains below the target for a certain period. Otherwise, right after merely hitting the target, inflation will bounce off like a flat stone skimming across the lake surface due to persistently high inflation expectations. (For a mathematical formulation of this logic, see the Appendix).

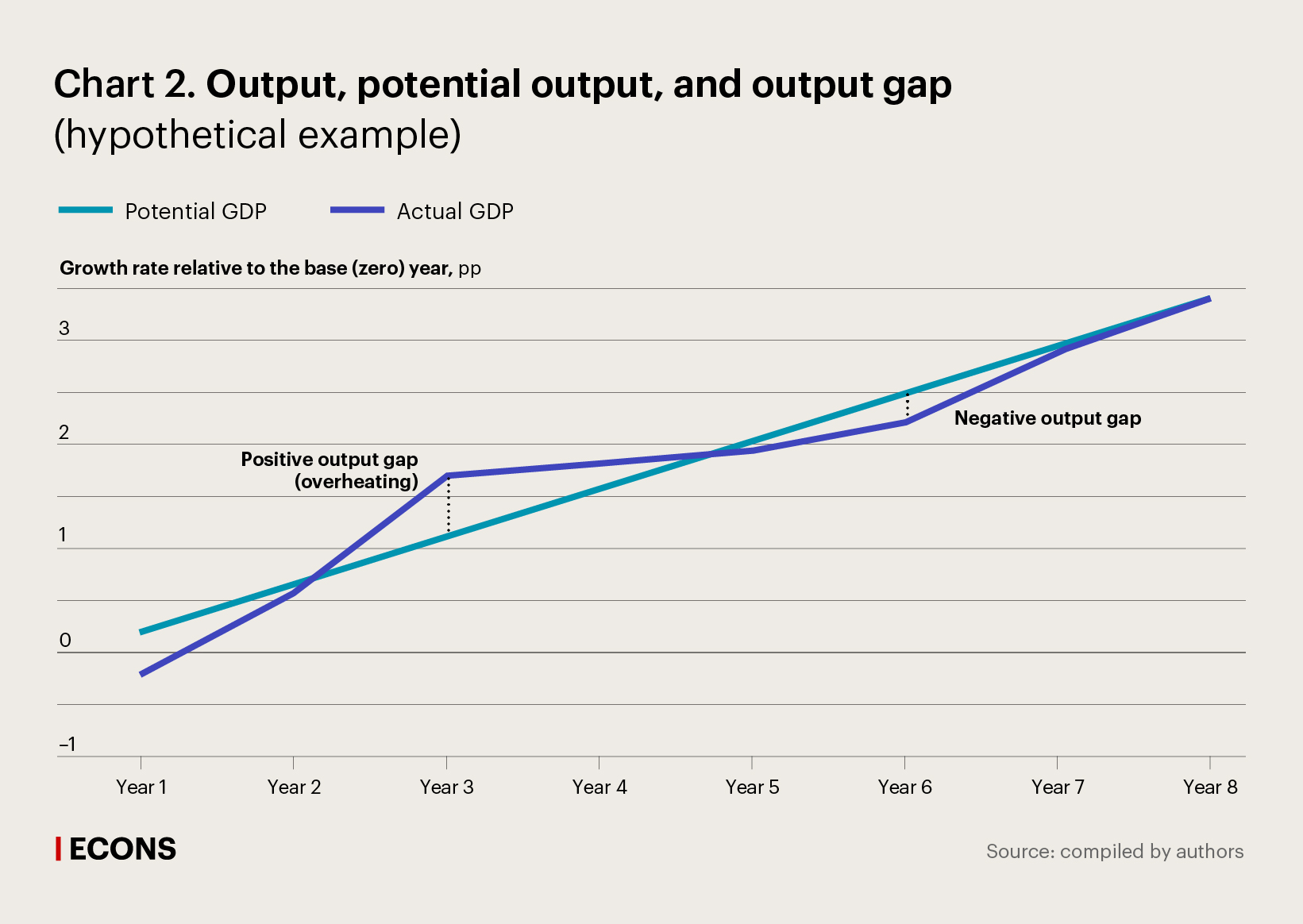

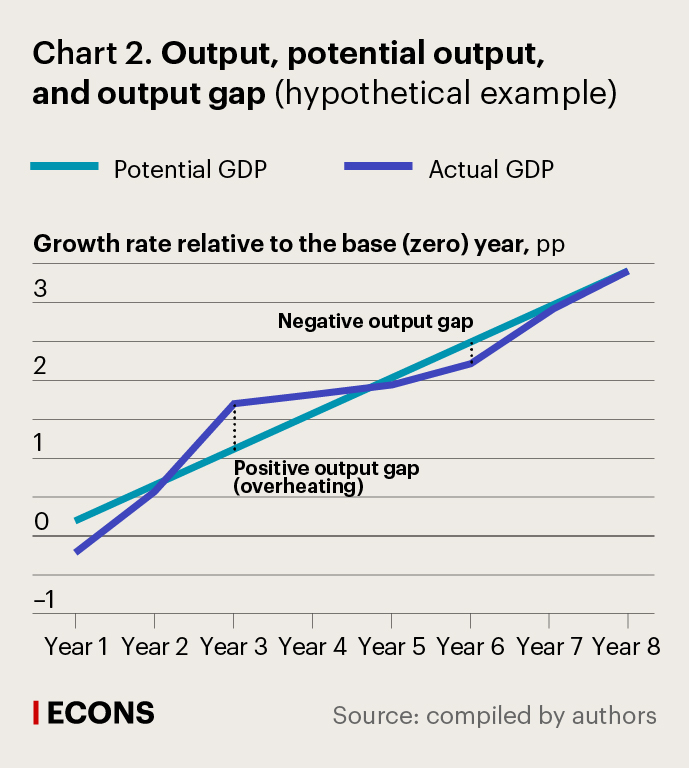

However, as the economy’s potential is not a constant value but grows over time, it is entirely possible to cool down the economy through a soft landing, without causing output to decrease (see Chart 2).

Potential output is determined by the capacity to produce goods and services that are in demand in a given economy under ‘normal’ operating conditions, without requiring overtime work. Technological and technical progress, returns on investments, the spread of more advanced and sustainable governance practices, and growth in the labour force increase the potential output. This gradual expansion in production capacities is exactly what constitutes sustainable growth.

A surge in output beyond its potential under the influence of demand-side stimuli is overheating. It accelerates inflation, and therefore, such growth cannot be considered sustainable as it leads to the accumulation of imbalances. If overheated demand (i.e. actual GDP) slows down and, for a certain period, increases at a pace lower than that of potential GDP, then, at some point, the potential will catch up to or even surpass demand (years 5–6 in Chart 2). This will ensure additional disinflationary effect that is needed to anchor inflation expectations.

Determining the degree of monetary policy tightness that would not only prevent a further rise in inflation expectations, but also ensure their timely decline, thereby returning inflation to the target without plunging the economy into recession, is quite a challenge. This is what the Bank of Russia strives to do when analysing the current situation and developing a forecast based on a wide range of scenario and model-based calculations and the professional judgement of its Board of Directors. Its main objective is to determine a monetary policy trajectory that would return the economy to a path of balanced and sustainable growth, i.e. would align demand expansion with the trajectory of potential GDP growth, while avoiding an excessively negative output gap. A large negative output gap leads to high unemployment and inflation significantly below the target. Countering this scenario is an integral part of the inflation targeting logic where the main goal is to keep inflation close to the target level.

Challenge 2: Non-linear nature of the Phillips curve

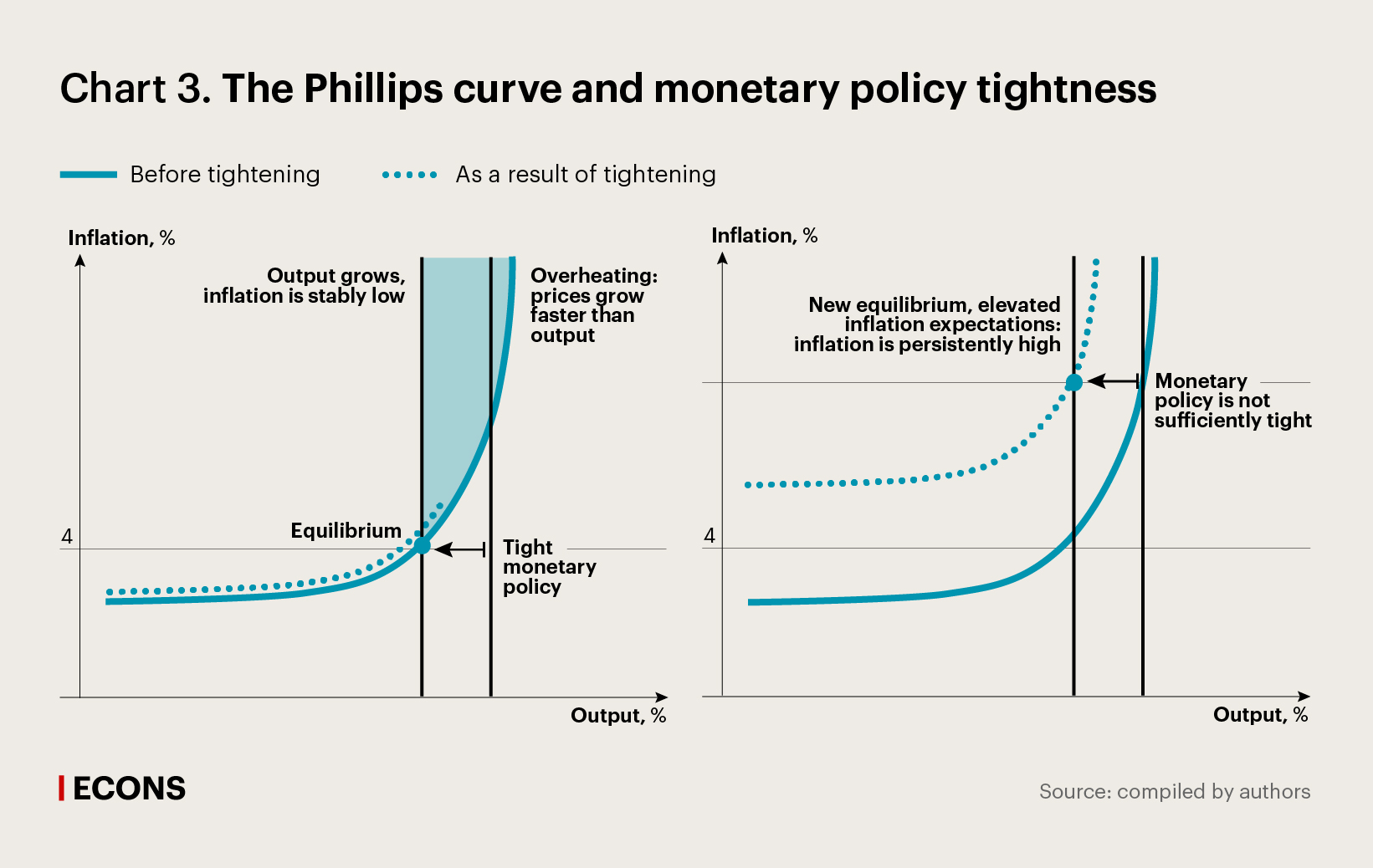

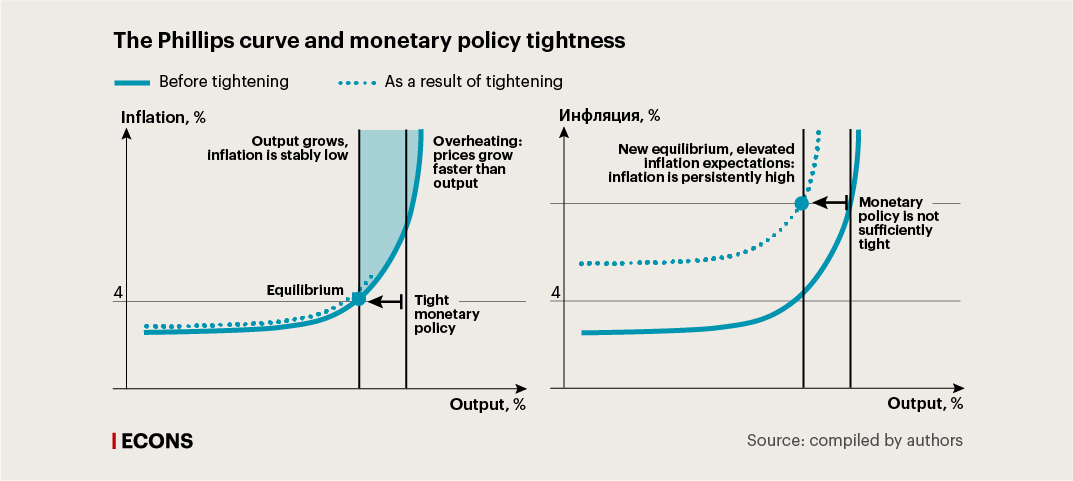

The impact of monetary policy on economic activity and inflation depends on the shape of the Phillips curve and the specific point on the curve where the economy is currently situated (see the diagram in Chart 3). The Phillips curve illustrates the relationship between the deviation from the equilibrium level of economic activity (unemployment) and the deviation of inflation from the target. Among economists, there is a growing consensus that the Phillips curve in the modern economy is non-linear and resembles a hyperbola in shape (rather than having become flat, as it seemed in the 2010s (link in Russian) during the period of ultra-low interest rates).

In a situation of overheating, which is characterised by a significant positive output gap and high inflation, the economy is located on the part of the Phillips curve that becomes progressively steeper and vertical (see the diagram in Chart 3). This means that pursuing tight monetary policy and constraining demand in such a scenario translates into decelerating price growth to a greater extent than into a slowdown in real physical output growth.

However, as, on the one hand, the gap between the dynamics of demand and supply (output) narrows and, on the other hand, inflation approaches its target, the situation will change. Specifically, the influence of monetary policy on output (which still exceeds potential GDP) will become increasingly more pronounced and its impact on prices will be relatively less notable.

If the final stage is not completed, inflation and inflation expectations will ‘stuck’ at elevated levels. This will not, however, boost economic growth. On the contrary, economic uncertainty will increase because higher inflation is typically more volatile. With high inflation volatility, it becomes quite difficult to figure out how to respond to demand growth – by expanding output or by raising prices. After all, an increase in demand for a company’s products might simply reflect competitors raising their prices more rapidly in response to overall cost increases. This amplifies uncertainty in production and investment decision-making, which in turn adversely impacts production and investment activity.

Challenge 3: Persistent proinflationary supply shocks

Another challenge for monetary policy is long-lasting (or back-to-back) proinflationary supply shocks pushing up marginal production costs.

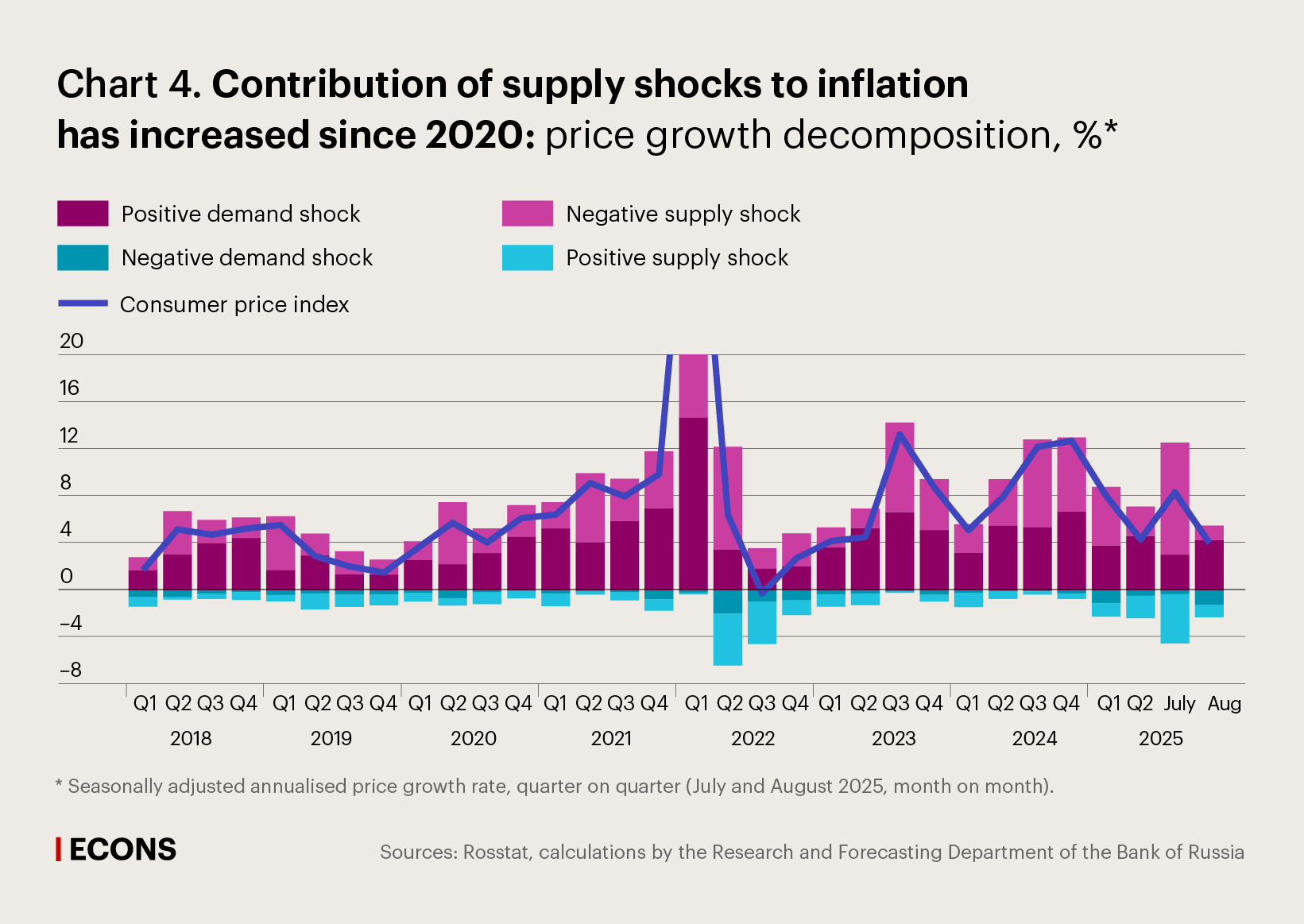

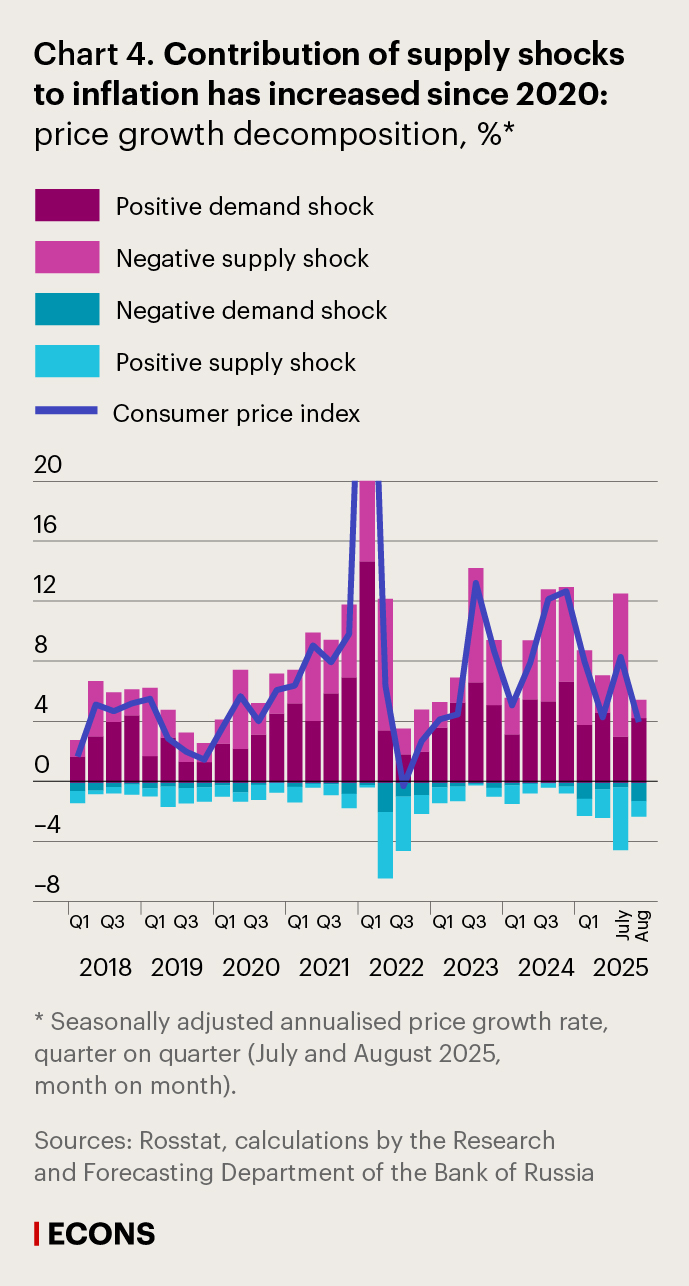

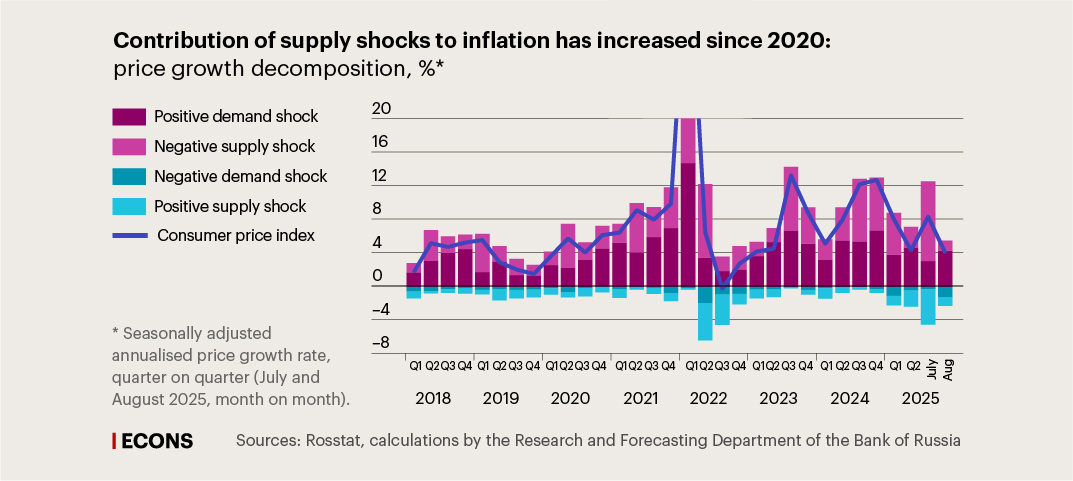

Examples include increasingly complicated and expensive supply chains, escalating tariff wars, as well as a sustained and significant rise in commodity prices. Such a commodity supercycle was observed in the early 2000s, and Russia, as a commodity exporter, was a beneficiary of this supercycle. In Russia, proinflationary supply shocks prevail, and their contribution to price growth has substantially increased after 2020.

Consequently, underestimating the aftereffects of these recurring supply shocks leads to actual inflation remaining persistently above the target.

However, if the regulator timely identifies the nature and duration of emerging shocks and responds to them with slightly tighter monetary policy, the economy will find itself below the equilibrium level. A negative output gap will emerge and persist until proinflationary supply shocks subside. In this scenario, inflation will be close to the target level. This will help keep inflation expectations anchored or facilitate their decline if they are unanchored.

The challenges for central banks of many countries discussed above are another confirmation of the fact that in order to achieve sustainably low inflation in Russia in the current environment, monetary conditions need to remain tight for an extended period. Nevertheless, this suggests a downward key rate path, provided that both price growth rates and inflation expectations decrease sustainably. Monetary policy, however, should remain restrictive until both inflation and inflation expectations stabilise at a low level.