Why Modern Central Banks Talk So Much

Today, when the public can learn about central banks’ decisions from social networks, it is difficult to imagine that this was not the case a relatively short time ago.

For example, until the 1980s, the US Federal Reserve did not communicate its rate decisions at all. The current format of communication was introduced only in 1993. Before that, there were no statements following the meetings of the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC), and no minutes of such meetings, no discussion materials, and certainly no press conferences were held. External experts tried to guess the rate target the members of the FOMC voted for at their regular meeting. To this end, they analysed the regulator’s daily operations in the open market. This process, known as ‘policy discovery’, was incredibly costly and inefficient.

Why did the Federal Reserve not announce its decisions right after they were taken? It was believed that the announcement of decisions had no practical value, which can hardly be true of the operations directly performed by the Federal Reserve. Communication for managing market expectations has not been considered a monetary policy tool for very long.

The best description of the dominant approach to communication in those days belongs to well-known economist and winner of the Adam Smith Prize Karl Brunner, who introduced the term ‘monetarism’. He noted that central banks have traditionally been surrounded by political mysticism as protection. ‘The political mystique of central banking was, and still is to some extent, widely expressed by an essentially metaphysical approach to monetary affairs and monetary policy-making. … The mystique thrives on a pervasive impression that central banking is an esoteric art. Access to this art and its proper execution is confined to the initiated elite. The esoteric nature of the art is moreover revealed by an inherent impossibility to articulate its insights in explicit and intelligible words and sentences. Communication with the uninitiated breaks down,’ – argued Brunner (as quoted in the book The Long Journey of Central Bank Communication by Otmar Issing, a retired board member of the Deutsche Bundesbank and the ECB).

Janet Yellen, head of the Federal Reserve in 2014–2018 and the incumbent United States Secretary of the Treasury, who began her career as an economist with the Federal Reserve’s international finance department in 1977, has recalled that secrecy of monetary policy decisions was considered the best policy in those years. According to her, the Federal Reserve avoided even mentioning its mandate directly, although the Congress demanded the maintenance of stable prices and maximum employment. Nevertheless, the mere mention of employment in the mandate, even in the mid-1990s, was described in a New York Times article as the equivalent of ‘sticking needles in the eyes of central bankers’.

The situation with the Bank of England was similar. The Bank of England was under great political pressure in the 1930s, as the British economy had been shaken by the Great Depression in the United States. In his book, Issing cites a typical dialogue of that time between the Deputy Chairman of the Bank of England and the members of the Finance and Industry Committee. They called on the Bank of England to start publishing an annual report and at the same time wondered why the Bank of England did not explain and defend its decisions. The answers were as follows: ‘It is a dangerous thing to start to give reasons’ and ‘As regards criticism, I am afraid [that] … to defend ourselves is somewhat akin to a lady starting to defend her virtue.’

This order of things seemed unshakable for a long time. But everything changed when, in the 1990s and early 2000s, central banks began to switch to inflation targeting policies: achieving the inflation target required that monetary regulators be independent in their decision-making, which, in turn, made them more transparent in the way their decisions were made and more accountable to the public.

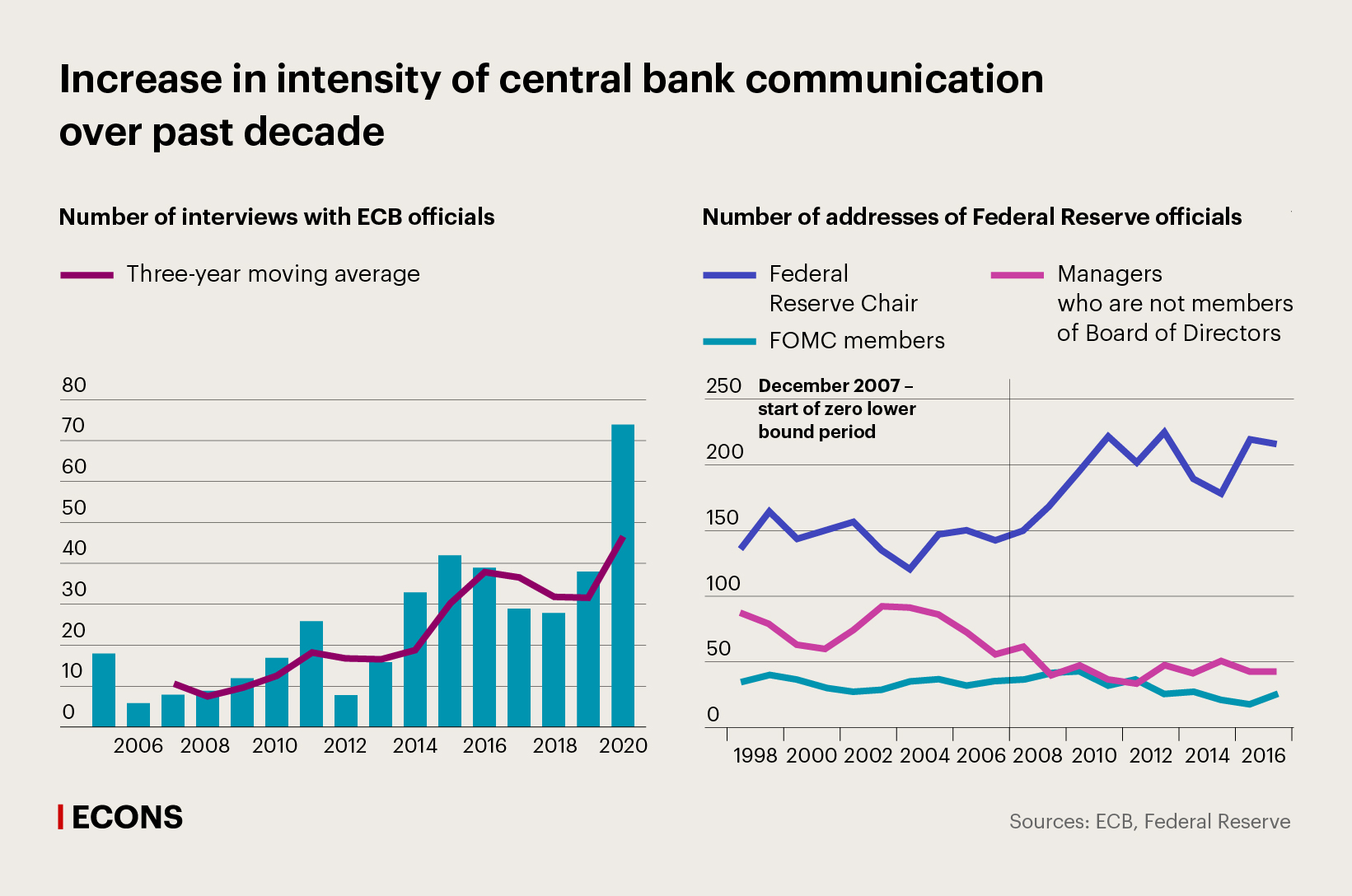

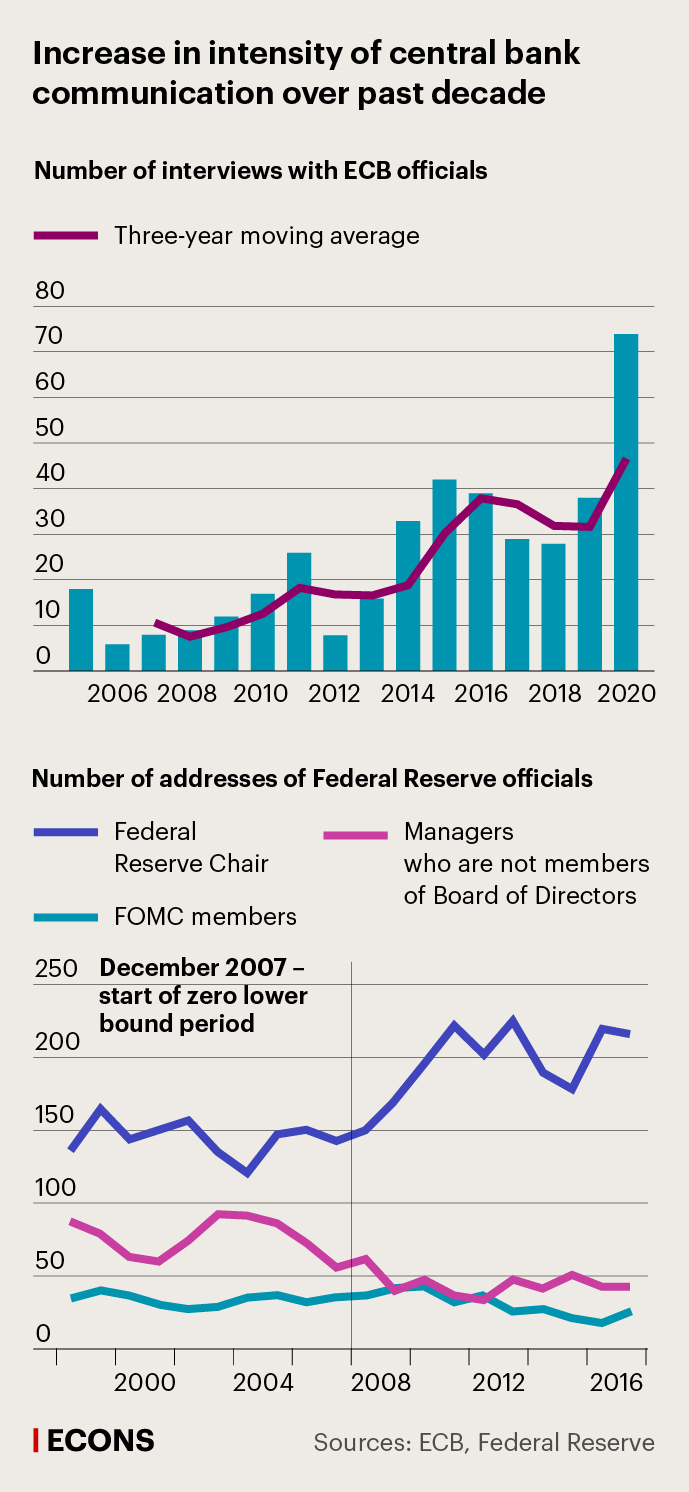

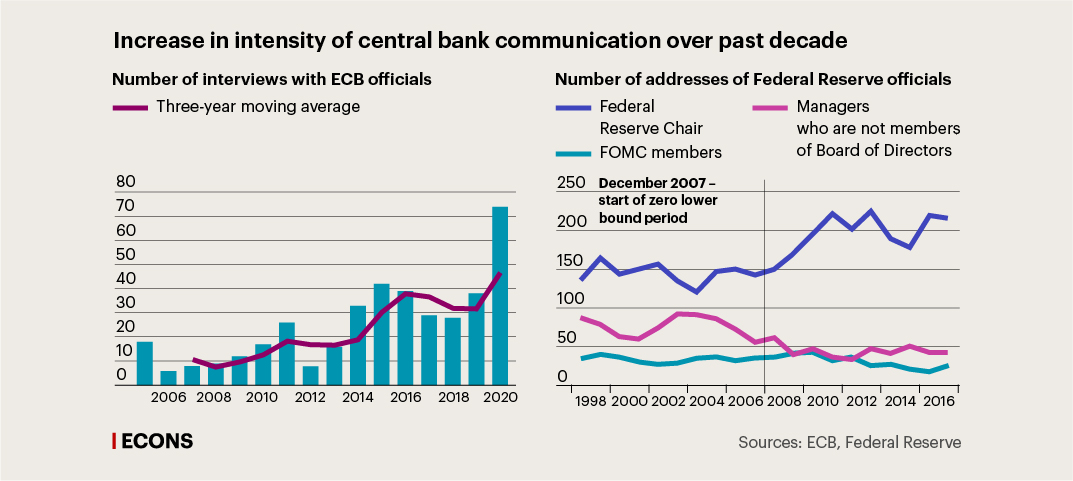

In the early 2010s, advanced economies faced the zero lower bound problem for nominal interest rates. This occurs when the central bank, in its response to a shock, must lower the interest rate, but the optimal interest rate is in the negative area and cannot be set. The response was a sharp increase in the intensity of central bank communication as a monetary policy tool.

The famous words ‘whatever it takes’ by ECB President Mario Draghi in July 2012 are the most striking example of the success of communication as a tool. His speech was a turnaround point in the European sovereign debt crisis. Due to the crisis, the yields on the securities of peripheral European countries rose sharply, which threatened to destabilise the euro area as a whole and may even have led to the rejection of the single currency. In response, Draghi confidently stated that the ECB would ‘do whatever it takes to preserve the euro’. His short but highly convincing speech made (link in Russian) an indelible impression on the markets, and yields declined drastically. As a result, the ECB did not have to spend a single euro to save the debt markets of the peripheral countries: although the regulator announced a programme for the purchase of their bonds, known as Outright Monetary Transactions, the need to use it never arose. A few words by Mario Draghi, said at the right time and in the right place, were enough to stabilise the markets.

Should central banks speak or remain silent?

Modern central banks also face a dilemma, however: whether to remain silent or to speak? Adherents of ‘silence’ believe that central banks are like surgeons who enjoy the complete trust of their sedated patients (society and the economy). The patient does not know what sort of manipulations the surgeon performs but believes in his or her skills. In this communication paradigm, the central bank focuses on communicating with market professionals and does not reach the wider audience, counting on its unconditional trust.

The ‘paradigm of silence’ is based on the idea of ’rational inattention’: it lies in the fact that economic agents are not able to analyse all information available, but that they can choose (link in Russian) which individual blocks of information to process. According to this idea, if the costs of the non-possession of information are low, then it can be ignored (such inattention is therefore rational). With regard to inflation, rational inattention is typical for countries with prolonged and successful experience in ensuring price stability.

The other school – active communication with the public – unites advanced economies with strong traditions of accountability of the authorities to the people and those emerging market economies whose populations are characterised by hyperreaction to incoming news. The first argument in defence of this paradigm is quite simple: to conduct independent monetary policy, the central bank needs support from the public. This is crucial when there is increasing political pressure on the monetary authorities. Trust is based on understanding, which is why it is important to talk to the people and explain actions as clearly as possible.

The second argument relates to the lack of ‘rational inattention’ to data on the dynamics of consumer prices among households in developing countries, which, as a rule, have difficult and painful experience of inflation in which price growth is many times higher than the rate of income growth. In this context, it would be naive to expect that people would remain calm in the event of an economic crisis and simply wait for the situation to return to normal. It is more logical to expect that they will begin urgently buying up non-perishable food products and imported household appliances, cash out savings, and convert their money in accounts into hard currency. These effects have been well studied not only in Russia, but also in Argentina, Peru, and Kazakhstan.

Therefore, for advanced economies, the choice of communication strategy is often only an illusion of choice. Talking convincingly is the only strategy. But how can this be done?

The gold standard of communication solutions

People who regularly follow central bank monetary policy announcements know that they have established procedures: press releases, press conferences, reports, and sometimes meeting minutes. Everything comes out according to a schedule known in advance. However, this format was not handed down from the heavens on emerald tablets. It was a painful challenge for central banks to address. In his book, A Modern History of FOMC Communication: 1975–2002, David E. Lindsey of the FOMC literally restores, on a day-to-day basis, the chronology of the evolutionary development of the Federal Reserve’s communication. His work recounts how the regulator first reduced the gap between the making of decisions and their publication, and then how the publications of these decisions gained detail, including meeting minutes. The advantage of emerging market economies is that they can take all of this experience and use it as a ‘package solution’.

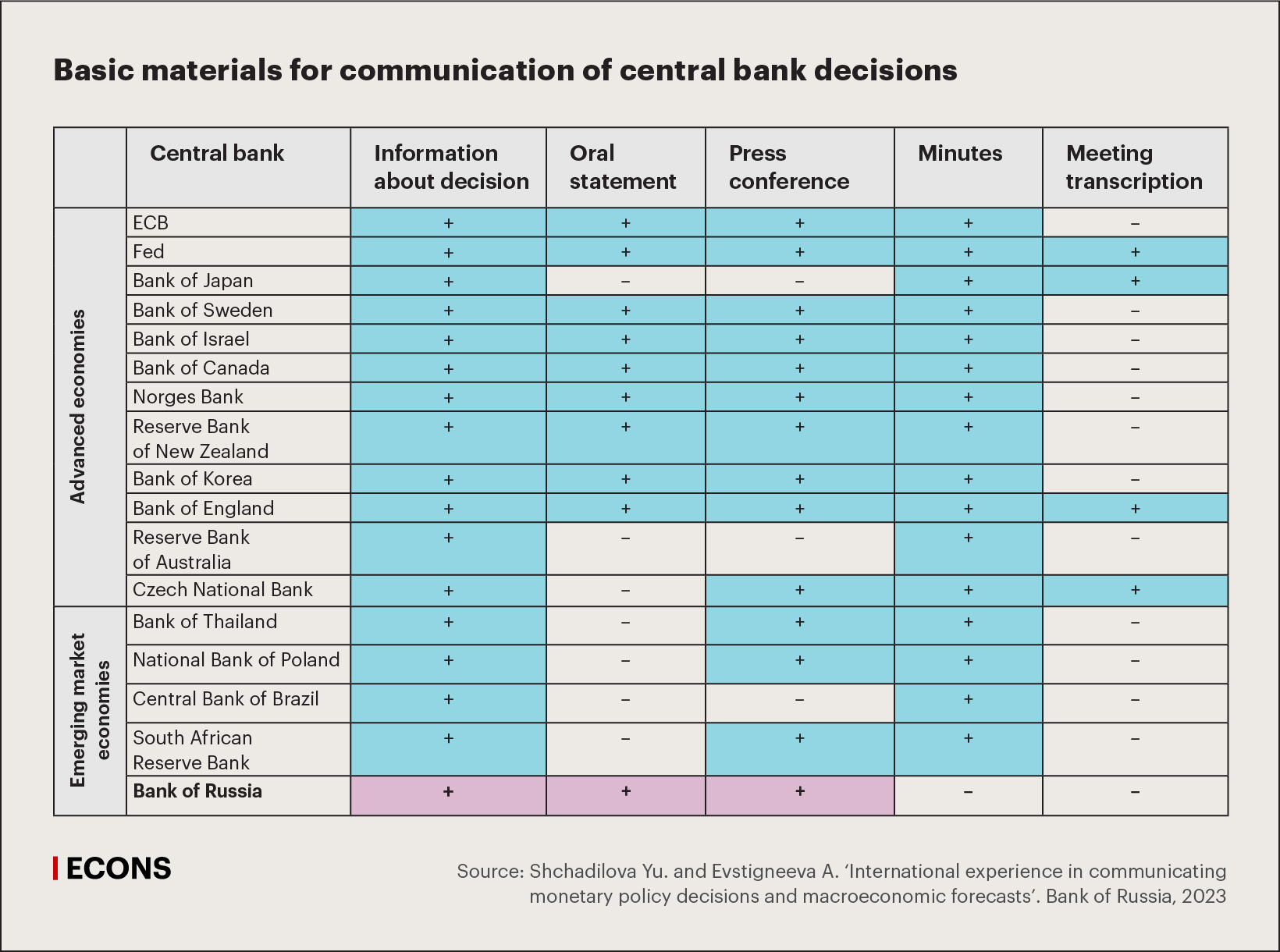

Issing has classified monetary policy communication tools and identified four levels. The first – basic – includes a press release, a press conference, and a transcript of the press conference. The second – additional communication – includes the minutes/discussion of the decision of the monetary policy committee and the publication of the voting results. The remaining two levels include a large list of additional communication, including speeches, lectures, reports, debates, booklets, and many other tools. The first two levels appear to be the absolute gold standard of communication.

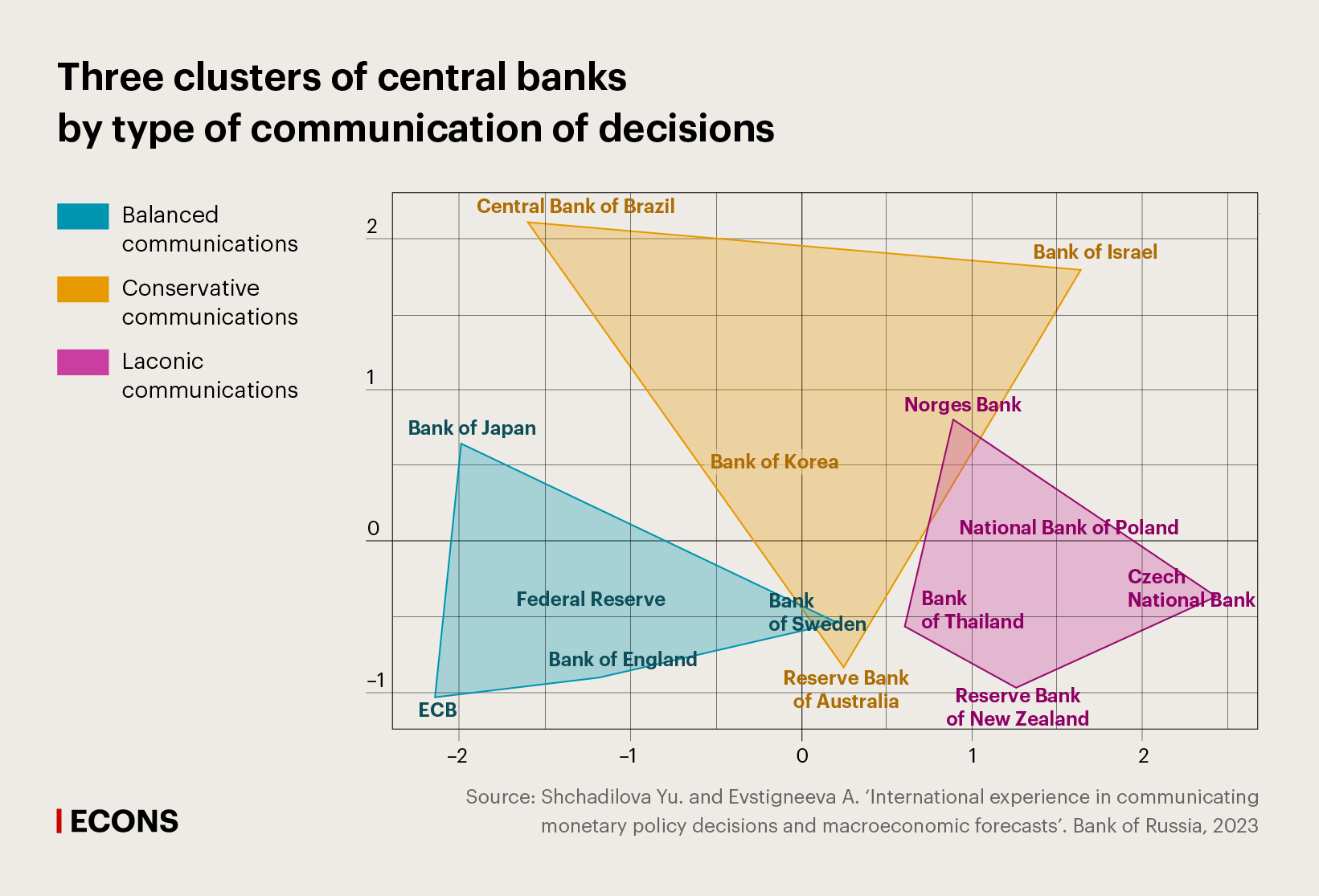

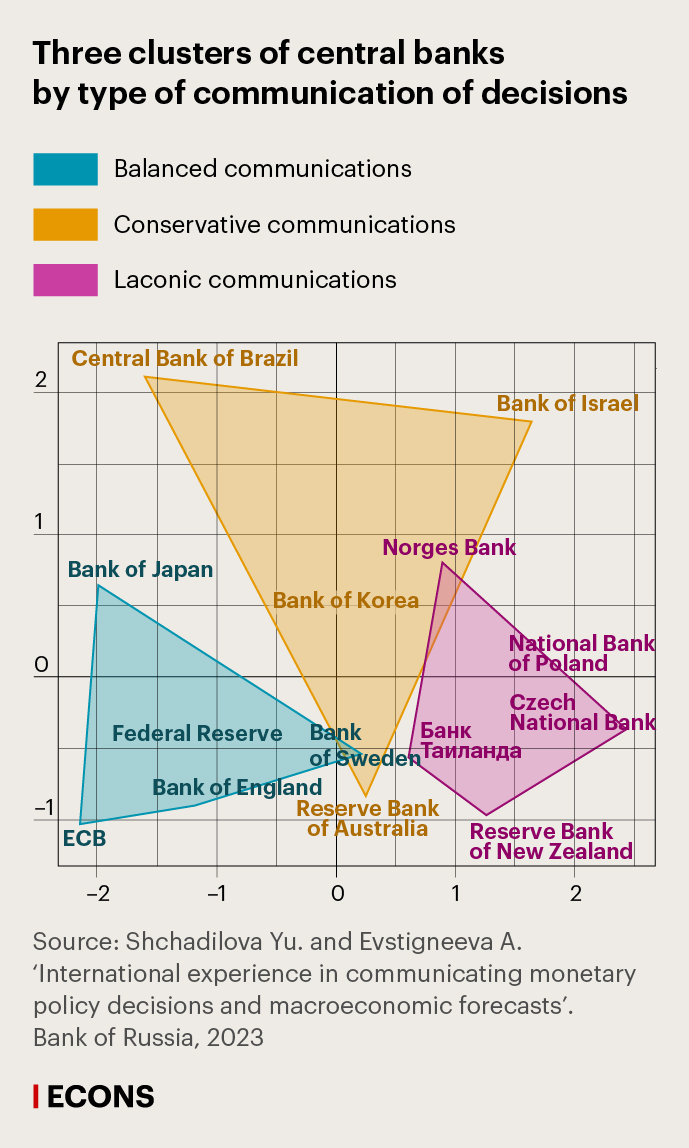

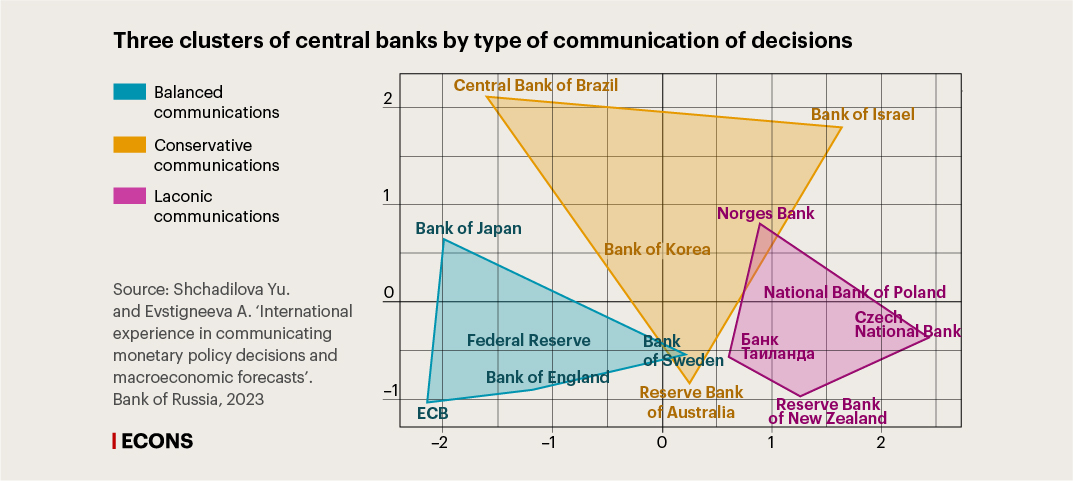

In our work, we examined the communication of 47 central banks that target inflation, and, for 17 of them, we conduct a machine text analysis for 2000–2022. As stated in Alan Blinder’s classic 2009 paper on inflation targeting, press releases and minutes are are substitutes, and they should be considered together. We go a little further and cluster the communication of monetary policy decisions by central banks that issue both press releases and minutes. With this in mind, we apply the k-means method, which is used to cluster data based on a vector space quantization algorithm. As a result, we obtain three conditional types of central bank communication.

The first, highlighted in red in the chart below, is a ‘laconic’ type of communication. It includes central banks that issue short press releases and minutes of any degree of similarity.

The second type, highlighted in yellow, is ‘conservative’. These are central banks that have a high level of similarity for all types of materials, although their volumes are different.

The third type, ‘balanced’, includes central banks that publish both short and standard press releases about decisions, but which also disclose detailed information in extensive and non-standard minutes.

Since this method requires four points, and the Bank of Russia has only two points, we can include the Bank of Russia in one of these groups only analytically as regards press releases. In our opinion, this can be done by the method of exclusion: the Bank of Russia’s materials on interest rate decisions are above average in length and below average in similarity, so it may potentially be grouped with the banks with a ‘balanced’ type of communication. In other words, it publishes short standard decisions and long explanatory minutes.

Costs of communication

With central banks ‘talking’ so much, a question inevitably arises: is there an objective limit to this activity? Is it possible to increase the volume of communication with no limits, or is there a turning point after which the effects become negative? For example, might there be so much information that it becomes noise and only prevents economic agents from correctly predicting decisions?

Perhaps the most interesting arguments in support of this point of view are presented in the recent work of experts from the central banks of Switzerland and Korea and the Swiss Financial Market Supervision Authority. The authors show that intensive communication, measured by the number of speeches delivered by central bankers per year, is detrimental to the perceived impact of central banks on the economy. Additionally, during the global financial crisis, this effect became even stronger. In such circumstances, economic agents may start searching for the ‘silver bullet’, or the final and most effective way to make their lives easier and reduce the costs of processing the huge amount of information from central banks. Indeed, we can see attempts to find the ‘silver bullet’ where central banks have succeeded in expanding communication. The ECB is the most striking example.

Credit Agricole analyst Louis Harreau investigated the possibility of predicting the decisions of the European regulator by the colour of Mario Draghi’s tie and the type of knot he uses (‘four-in-hand’ or ‘full Windsor’). The analyst concluded that the tie had nothing to do with future decisions. Nevertheless, analysts were so carried away with the idea of analysing solutions that they even played #draghitieguesses on a popular social network. As a result, Michael Steen, the press secretary of the head of the ECB, had to comment on this interest in ties, explaining that the choice of colour was definitely not on the list of priorities at ECB Governing Council meetings.

Alas, according to Murphy’s law, complex problems always have simple and easy-to-understand incorrect solutions. In an ever-changing economic environment, under the pressure of new shocks, central banks must analyse hundreds of factors before deciding on interest rates. They use advanced forecasting models and prepare research to do their jobs better. And analysts whose duties include forecasting decisions have no choice but to do the same. There is no chance they can succeed by relying on the colour of ties. Central bank rate decisions are based on the work of many economists who continuously analyse and forecast the economy in all possible areas. No matter how much anyone might like to find a ‘silver bullet’ to simplify this work, it is useless, because no silver bullet exists.

Most central banks try to provide information to the market so that the understanding and methods of analysts are close to those used by the monetary authorities. Lists for transparency indices are used to assess the sufficiency of such efforts. The popular one is the transparency index developed by IMF experts specifically for central banks which use the common inflation targeting. Among other things, its criteria include the publication of the codes of the model framework, records of decisions, and the clear communication of goals and decisions. The Bank of Russia has fulfilled most of the transparency criteria from this list, and it continues to actively develop its monetary policy communication.